Ancient Egyptian cuisine

| Ancient Egyptian culture |

|---|

|

The cuisine of ancient Egypt covers a span of over three thousand years, but still retained many consistent traits until well into

Meals

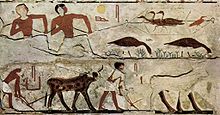

Depictions of

Food could be prepared by

Bread

Egyptian bread was made almost exclusively from emmer wheat, which was more difficult to turn into flour than most other varieties of wheat. The chaff does not come off through threshing, but comes in spikelets that needed to be removed by moistening and pounding with a pestle to avoid crushing the grains inside. It was then dried in the sun, winnowed and sieved and finally milled on a saddle quern, which functioned by moving the grindstone back and forth, rather than with a rotating motion.[3]

The baking techniques varied over time. In the Old Kingdom, heavy pottery molds were filled with dough and then set in the embers to bake. During the Middle Kingdom tall cones were used on square hearths. In the New Kingdom a new type of a large open-topped clay oven, cylindrical in shape, was used, which was encased in thick mud bricks and mortar.[3]

Dough was then slapped on the heated inner wall and peeled off when done, similar to how a tandoor oven is used for flatbreads. Tombs from the New Kingdom show images of bread in many different shapes and sizes. Loaves shaped like human figures, fish, various animals and fans, all of varying dough texture. Flavorings used for bread included coriander seeds and dates, but it is not known if this was ever used by the poor.[3]

Other than emmer, barley was grown to make bread and also used for making beer, and so were lily seeds and roots, and tiger nut. The grit from the quern stones used to grind the flour mixed in with bread was a major source of tooth decay due to the wear it produced on the enamel. For those who could afford there was also fine dessert bread and cakes baked from high-grade flour.[2]

-

Small table of reeds and stems of papyrus.New Kingdom, between 1425 and 1353 BC. AD, from the Tomb of Kha and Merit, Deir el-Medina. Museo Egizio, Turin.

Beer

In Egypt beer was a primary source of nutrition, and consumed daily. Beer was such an important part of the Egyptian diet that it was even used as currency.[4] Like most modern African beers, but unlike European beer, it was very cloudy with plenty of solids and highly nutritious, quite reminiscent of gruel. It was an important source of protein, minerals and vitamins and was so valuable that beer jars were often used as a measurement of value and were used in medicine. Little is known about specific types of beer, but there is mention of, for example, sweet beer but without any specific details mentioned.

Globular-based vessels with a narrow neck that were used to store fermented beer

Archeological evidence shows that beer was made by first baking "beer bread", a type of well-

Microscopy of beer residue points to a different method of brewing where bread was not used as an ingredient. One batch of grain was sprouted, which produced enzymes. The next batch was cooked in water, dispersing the starch and then the two batches were mixed. The enzymes began to consume the starch to produce sugar. The resulting mixture was then sieved to remove chaff, and yeast (and probably lactic acid) was then added to begin a fermentation process that produced alcohol. This method of brewing is still used in parts of non-industrialized Africa. Most beers were made of barley and only a few of emmer wheat, but so far no evidence of flavoring has been found.[9]

Fruit and vegetables

Vegetables were eaten as a complement to the ubiquitous beer and bread; the most common were long-shooted green

were eaten raw, boiled, roasted or ground into flour and were rich in nutrients.Tiger nut ( as early as the 4th Dynasty.

The most common fruit were dates and there were also figs, grapes (and raisins), dom palm nuts (eaten raw or steeped to make juice), certain species of Mimusops, and nabk berries (jujube or other members of the genus Ziziphus).[2] Figs were so common because they were high in sugar and protein. The dates would either be dried/dehydrated or eaten fresh. Dates were sometimes even used to ferment wine and the poor would use them as sweeteners. Unlike vegetables, which were grown year-round, fruit was more seasonal. Pomegranates and grapes would be brought into tombs of the deceased.

Meat, fowl and fish

Meat came from domesticated animals, game and poultry. This possibly included partridge, quail, pigeon, ducks and geese. The chicken most likely arrived around the 5th to 4th century BC, though no chicken bones have actually been found dating from before the Greco-Roman period. The most important animals were cattle, sheep, goats and pigs (previously thought to have been taboo to eat because the priests of Egypt referred pig to the evil god Seth).[11]

5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotus claimed that the Egyptians abstained from consuming female cows as they were sacred by association with Isis. They sacrificed male oxen that were inspected to be clean and free of disease and ate the remainder after it was ritually burned. Ill or diseased male oxen not worthy of sacrifice and had died were buried ritually and then dug up after the bones were clean and placed in a temple. Only the heads of the male oxen that were cut off and then cursed were available to be eaten by the Greeks in Egypt as they were not allowed of the sacred sacrifice meat.[12] Excavations at the Giza worker's village have uncovered evidence of massive slaughter of oxen, sheep and pigs, such that researchers estimate that the workforce building the Great Pyramid were fed beef every day.[11]

A 14th century book translated and published in 2017 lists 10 recipes for sparrow which was eaten for its aphrodisiac properties.[17]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; banquets

- ^ a b c d e The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; diet

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; bread

- S2CID 162357890.

- S2CID 162357890.

- ^ Rayment, W.J. "History of Bread". www.breadinfo.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Caballero, Benjamin; Finglas, Paul; Toldrá, Fidel. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Academic Press. p. 348.

- ^ Jensen, Jon. "Poor of Cairo drown their sorrows in moonshine". jonjensen. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt; beer

- ^ Hawass, Zahi, Mountains of the Pharaohs, Doubleday, New York, 2006. p. 165.

- ^ a b Hawass, Zahi, Mountains of the Pharaohs, Doubleday, New York, 2006. p. 211.

- ^ "HERODOTUS: Chapter II:41". Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ "HERODOTUS: Chapter II:47". Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ "Ancient Egypt: Farmed and domesticated animals". Archived from the original on 2017-12-16. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "A Global Taste Test of Foie Gras and Truffles". NPR. Archived from the original on 2018-07-14. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ^ Myhrvold, Nathan. "Cooking". Britannica. Britannica. Archived from the original on 2017-12-07. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Further reading

- Fortin, Jacey (2019-08-08). "Ancient Egyptian Yeast Is This Bread's Secret Ingredient". The New York Times. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- Thurler, Kim (2021-03-18). "Bake Like an Egyptian". Tufts Now. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

External links

- Food: Bread, beer, and all good things, reshafim.org.il, 2000–2005.