Conscience

A conscience is a cognitive process that elicits

Religious views of conscience usually see it as linked to a morality inherent in all humans, to a beneficent universe and/or to

Commonly used metaphors for conscience include the "voice within", the "inner light",

Views

Although humanity has no generally accepted definition of conscience or universal agreement about its role in ethical decision-making, three approaches have addressed it:[8]

Religious

In the literary traditions of the

In the

Conscience also features prominently in

The

The

In the Protestant Christian tradition,

This dilemma of obedience in conscience to divine or state law, was demonstrated dramatically in

Secular

The secular approach to conscience includes psychological, physiological, sociological, humanitarian, and authoritarian views.[53] Lawrence Kohlberg considered critical conscience to be an important psychological stage in the proper moral development of humans, associated with the capacity to rationally weigh principles of responsibility, being best encouraged in the very young by linkage with humorous personifications (such as Jiminy Cricket) and later in adolescents by debates about individually pertinent moral dilemmas.[54] Erik Erikson placed the development of conscience in the 'pre-schooler' phase of his eight stages of normal human personality development.[55] The psychologist Martha Stout terms conscience "an intervening sense of obligation based in our emotional attachments."[56] Thus a good conscience is associated with feelings of integrity, psychological wholeness and peacefulness and is often described using adjectives such as "quiet", "clear" and "easy".[57]

Conscience as a society-forming instinct

Charles Darwin considered that conscience evolved in humans to resolve conflicts between competing natural impulses-some about self-preservation but others about safety of a family or community; the claim of conscience to moral authority emerged from the "greater duration of impression of social instincts" in the struggle for survival.[62] In such a view, behavior destructive to a person's society (either to its structures or to the persons it comprises) is bad or "evil".[63] Thus, conscience can be viewed as an outcome of those biological drives that prompt humans to avoid provoking fear or contempt in others; being experienced as guilt and shame in differing ways from society to society and person to person.[64] A requirement of conscience in this view is the capacity to see ourselves from the point of view of another person.[65] Persons unable to do this (psychopaths, sociopaths, narcissists) therefore often act in ways which are "evil".[66]

Fundamental in this view of conscience is that humans consider some "other" as being in a social relationship. Thus,

An interesting area of research in this context concerns the similarities between our relationships and those of

Evolutionary biology

Contemporary scientists in

Neuroscience and artificial conscience

Numerous case studies of

Attempts have been made by neuroscientists to locate the free will necessary for what is termed the 'veto' of conscience over unconscious mental processes (see Neuroscience of free will and Benjamin Libet) in a scientifically measurable awareness of an intention to carry out an act occurring 350–400 microseconds after the electrical discharge known as the 'readiness potential.'[79][80][81]

Jacques Pitrat claims that some kind of artificial conscience is beneficial in artificial intelligence systems to improve their long-term performance and direct their introspective processing.[82]

Philosophical

The word "conscience" derives etymologically from the Latin conscientia, meaning "privity of knowledge"[83] or "with-knowledge". The

Medieval

The medieval

- Nafs Ammarah (12:53) which "exhorts one to freely indulge in gratifying passions and instigates to do evil"

- Nafs Lawammah (75:2) which is "the conscience that directs man towards right or wrong"

- Nafs Mutmainnah (89:27) which is "a self that reaches the ultimate peace"

The medieval Persian philosopher and physician

Some medieval Christian

In the 13th century,

Aquinas reasoned that acting contrary to conscience is an

Modern

As the sacred texts of ancient

Other philosophers expressed a more sceptical and pragmatic view of the operation of "conscience" in society.[113]

Josiah Royce (1855–1916) built on the transcendental idealism view of conscience, viewing it as the ideal of life which constitutes our moral personality, our plan of being ourself, of making common sense ethical decisions. But, he thought, this was only true insofar as our conscience also required loyalty to "a mysterious higher or deeper self".[120] In the modern Christian tradition this approach achieved expression with

As Hannah Arendt pointed out, however, (following the utilitarian John Stuart Mill on this point): a bad conscience does not necessarily signify a bad character; in fact only those who affirm a commitment to applying moral standards will be troubled with remorse, guilt or shame by a bad conscience and their need to regain integrity and wholeness of the self.[124][125] Representing our soul or true self by analogy as our house, Arendt wrote that "conscience is the anticipation of the fellow who awaits you if and when you come home."[126] Arendt believed that people who are unfamiliar with the process of silent critical reflection about what they say and do will not mind contradicting themselves by an immoral act or crime, since they can "count on its being forgotten the next moment;" bad people are not full of regrets.[126] Arendt also wrote eloquently on the problem of languages distinguishing the word consciousness from conscience. One reason, she held, was that conscience, as we understand it in moral or legal matters, is supposedly always present within us, just like consciousness: "and this conscience is also supposed to tell us what to do and what to repent; before it became the lumen naturale or Kant's practical reason, it was the voice of God."[127]

Albert Einstein, as a self-professed adherent of humanism and rationalism, likewise viewed an enlightened religious person as one whose conscience reflects that he "has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value."[128] Einstein often referred to the "inner voice" as a source of both moral and physical knowledge: "Quantum mechanics is very impressive. But an inner voice tells me that it is not the real thing. The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings one closer to the secrets of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice."[129]

Simone Weil who fought for the French resistance (the Maquis) argued in her final book The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind that for society to become more just and protective of liberty, obligations should take precedence over rights in moral and political philosophy and a spiritual awakening should occur in the conscience of most citizens, so that social obligations are viewed as fundamentally having a transcendent origin and a beneficent impact on human character when fulfilled.[130][131] Simone Weil also in that work provided a psychological explanation for the mental peace associated with a good conscience: "the liberty of men of goodwill, though limited in the sphere of action, is complete in that of conscience. For, having incorporated the rules into their own being, the prohibited possibilities no longer present themselves to the mind, and have not to be rejected."[132]

Alternatives to such

The French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir in A Very Easy Death (Une mort très douce, 1964) reflects within her own conscience about her mother's attempts to develop such a moral sympathy and understanding of others.[137]

"The sight of her tears grieved me; but I soon realised that she was weeping over her failure, without caring about what was happening inside me ... We might still have come to an understanding if, instead of asking everybody to pray for my soul, she had given me a little confidence and sympathy. I know now what prevented her from doing so: she had too much to pay back, too many wounds to salve, to put herself in another's place. In actual doing she made every sacrifice, but her feelings did not take her out of herself. Besides, how could she have tried to understand me since she avoided looking into her own heart? As for discovering an attitude that would not have set us apart, nothing in her life had ever prepared her for such a thing: the unexpected sent her into a panic, because she had been taught never to think, act or feel except in a ready-made framework."

— Simone de Beauvoir. A Very Easy Death. Penguin Books. London. 1982. p. 60.

Michael Walzer claimed that the growth of religious toleration in Western nations arose amongst other things, from the general recognition that private conscience signified some inner divine presence regardless of the religious faith professed and from the general respectability, piety, self-limitation, and sectarian discipline which marked most of the men who claimed the rights of conscience.[138] Walzer also argued that attempts by courts to define conscience as a merely personal moral code or as sincere belief, risked encouraging an anarchy of moral egotisms, unless such a code and motive was necessarily tempered with shared moral knowledge: derived either from the connection of the individual to a universal spiritual order, or from the common principles and mutual engagements of unselfish people.[139] Ronald Dworkin maintains that constitutional protection of freedom of conscience is central to democracy but creates personal duties to live up to it: "Freedom of conscience presupposes a personal responsibility of reflection, and it loses much of its meaning when that responsibility is ignored. A good life need not be an especially reflective one; most of the best lives are just lived rather than studied. But there are moments that cry out for self-assertion, when a passive bowing to fate or a mechanical decision out of deference or convenience is treachery, because it forfeits dignity for ease."[140] Edward Conze stated it is important for individual and collective moral growth that we recognise the illusion of our conscience being wholly located in our body; indeed both our conscience and wisdom expand when we act in an unselfish way and conversely "repressed compassion results in an unconscious sense of guilt."[141]

The philosopher Peter Singer considers that usually when we describe an action as conscientious in the critical sense we do so in order to deny either that the relevant agent was motivated by selfish desires, like greed or ambition, or that he acted on whim or impulse.[142]

Moral anti-realists debate whether the moral facts necessary to activate conscience

John Ralston Saul expressed the view in The Unconscious Civilization that in contemporary developed nations many people have acquiesced in turning over their sense of right and wrong, their critical conscience, to technical experts; willingly restricting their moral freedom of choice to limited consumer actions ruled by the ideology of the free market, while citizen participation in public affairs is limited to the isolated act of voting and private-interest lobbying turns even elected representatives against the public interest.[150]

Some argue on religious or philosophical grounds that it is blameworthy to act against conscience, even if the judgement of conscience is likely to be erroneous (say because it is inadequately informed about the facts, or prevailing moral (humanist or religious), professional ethical, legal and human rights norms). In other words, the welcoming of the Other, to Levinas, was the very essence of conscience properly conceived; it encouraged our ego to accept the fallibility of assuming things about other people, that selfish

Conscientious acts and the law

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, English litigants began to petition the Lord Chancellor of England for relief from unjust judgments.[154] As Keeper of the King's Conscience, the Chancellor intervened to allow for "merciful exceptions" to the King's laws, "to ensure that the King's conscience was right before God".[154] The Chancellor's office evolved into the Court of Chancery and the Chancellor's decisions evolved into the body of law known as equity.[154]

English humanist lawyers in the 16th and 17th centuries interpreted conscience as a collection of universal principles given to man by god at creation to be applied by reason; this gradually reforming the medieval

"Unjust laws exist; shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavour to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? ... A man has not everything to do but something; and because he cannot do everything, it is not necessary that he should do something wrong ... It is for no particular item in the tax bill that I refuse to pay it. I simply wish to refuse allegiance to the State, to withdraw and stand aloof from it effectually. I do not care to trace the course of my dollar if I could, till it buys a man, or a musket to shoot one with—the dollar is innocent—but I am concerned to trace the effects of my allegiance ... Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience, then?"

— Henry David Thoreau. Civil Disobedience. 1848. reprinted Signet Classic, New York. 1960 pp. 228, 229, 236.

In the

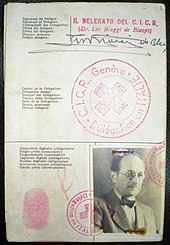

Notable historical examples of conscientious noncompliance in a different professional context included the manipulation of the visa process in 1939 by Japanese Consul-General

The controversialWorld conscience

World conscience is the

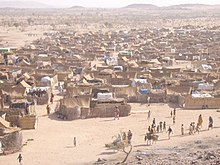

Often this derives from a

The microcredit initiatives of Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus have been described as inspiring a "war on poverty that blends social conscience and business savvy".[203]

The

The American cardiologist

A challenge to world conscience was provided by an influential 1968 article by

The philosopher Peter Singer has argued that the United Nations Millennium Development Goals represent the emergence of an ethics based not on national boundaries but on the idea of one world.[211] Ninian Smart has similarly predicted that the increase in global travel and communication will gradually draw the world's religions towards a pluralistic and transcendental humanism characterized by an "open spirit" of empathy and compassion.[212]

Notable examples of modern acts based on conscience

In a notable contemporary act of conscience, Christian bushwalker

Conscience played a major role in the actions by

At the awards ceremony for the

Conscience was a factor inIn literature, art, film, and music

The ancient epic of the Indian subcontinent, the

Bradley develops a theory about Hamlet's moral agony relating to a conflict between "traditional" and "critical" conscience: "The conventional moral ideas of his time, which he shared with the Ghost, told him plainly that he ought to avenge his father; but a deeper conscience in him, which was in advance of his time, contended with these explicit conventional ideas. It is because this deeper conscience remains below the surface that he fails to recognise it, and fancies he is hindered by cowardice or sloth or passion or what not; but it emerges into light in that speech to Horatio. And it is just because he has this nobler moral nature in him that we admire and love him".[265] The opening words of Shakespeare's Sonnet 94 ("They that have pow'r to hurt, and will do none") have been admired as a description of conscience.[266] So has John Donne's commencement of his poem s:Goodfriday, 1613. Riding Westward: "Let man's soul be a sphere, and then, in this, Th' intelligence that moves, devotion is;"[267]

Anton Chekhov in his plays The Seagull, Uncle Vanya and Three Sisters describes the tortured emotional states of doctors who at some point in their careers have turned their back on conscience.[268] In his short stories, Chekhov also explored how people misunderstood the voice of a tortured conscience. A promiscuous student, for example, in The Fit describes it as a "dull pain, indefinite, vague; it was like anguish and the most acute fear and despair ... in his breast, under the heart" and the young doctor examining the misunderstood agony of compassion experienced by the factory owner's daughter in From a Case Book calls it an "unknown, mysterious power ... in fact close at hand and watching him."[269] Characteristically, Chekhov's own conscience drove him on the long journey to Sakhalin to record and alleviate the harsh conditions of the prisoners at that remote outpost. As Irina Ratushinskaya writes in the introduction to that work: "Abandoning everything, he travelled to the distant island of Sakhalin, the most feared place of exile and forced labour in Russia at that time. One cannot help but wonder why? Simply, because the lot of the people there was a bitter one, because nobody really knew about the lives and deaths of the exiles, because he felt that they stood in greater need of help that anyone else. A strange reason, maybe, but not for a writer who was the epitome of all the best traditions of a Russian man of letters. Russian literature has always focused on questions of conscience and was, therefore, a powerful force in the moulding of public opinion."[270]

The Robert Bolt play A Man For All Seasons focuses on the conscience of Catholic lawyer Thomas More in his struggle with King Henry VIII ("the loyal subject is more bounden to be loyal to his conscience than to any other thing").[276] George Orwell wrote his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four on the isolated island of Jura, Scotland to describe how a man (Winston Smith) attempts to develop critical conscience in a totalitarian state which watches every action of the people and manipulates their thinking with a mixture of propaganda, endless war and thought control through language control (double think and newspeak) to the point where prisoners look up to and even love their torturers.[277] In the Ministry of Love, Winston's torturer (O'Brien) states: "You are imagining that there is something called human nature which will be outraged by what we do and will turn against us. But we create human nature. Men are infinitely malleable".[278]

A tapestry copy of

The

The 1957

The 1982 Ridley Scott film Blade Runner focuses on the struggles of conscience between and within a bounty hunter (Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford)) and a renegade replicant android (Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer)) in a future society which refuses to accept that forms of artificial intelligence can have aspects of being such as conscience.[285]

The

The

See also

- Amity-enmity complex

- An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, chapter XXVII: "Of Identity and Diversity"

- Altruism

- Confidant

- Conscientious objector

- Conscientiousness

- Consciousness

- Ethics

- Evolutionary ethics

- Evolution of morality

- Free will

- Guilt

- Inner light

- Jiminy Cricket, symbol of conscience in Pinocchio (1940 film)

- List of nonviolence scholars and leaders

- Mind–body problem

- Moral emotions

- Moral value

- Morality

- Outline of self

- Philosophy of mind

- Rationality and power

- Rationality

- Reason

- Sraosha, Deity of Conscience

- Social conscience

- Subtle body

- Synderesis

Further reading

- Slater S.J., Thomas (1925). . A manual of moral theology for English-speaking countries. Burns Oates & Washbourne Ltd.

References

- ^ Ninian Smart. The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations. Cambridge University Press. 1989. pp. 10–21.

- ^ Peter Winch. Moral Integrity. Basil Blackwell. Oxford. 1968

- ^ ISBN 978-0-271-01988-8,

- ^ a b "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ a b Booth K, Dunne T and Cox M (eds). How Might We Live? Global Ethics in the New Century. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge 2001 p. 1.

- ^ a b Amnesty International. Ambassador of Conscience Award. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Wayne C Booth. The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction. University of California Press. Berkeley. 1988. p. 11 and Ch. 2.

- ^ ISBN 0-271-02070-9p. 176

- ^ Ninian Smart. The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 382

- Veka-Chudamani) (trans Prabhavananda S and Isherwood C). Vedanta Press, Hollywood. 1978. pp. 34–36, 136–37.

- Veka-Chudamani) (trans Prabhavananda S and Isherwood C). Vedanta Press, Hollywood. 1978. p. 119.

- ^ John B Noss. Man's Religions. Macmillan. New York. 1968. p. 477.

- ^ AS Cua. Moral Vision and Tradition: Essays in Chinese Ethics. Catholic University of America Press. Washington. 1998.

- ^ Jayne Hoose (ed) Conscience in World Religions. University of Notre Dame Press. 1990.

- ^ Ninian Smart. The Religious Experience of Mankind. Fontana. 1971 p. 118.

- ^ Santideva. The Bodhicaryavatara. trans Crosby K and Skilton A. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1995. pp. 38, 98

- ^ Lama Anagarika Govinda in Jeffery Paine (ed) Adventures with the Buddha: A Buddhism Reader. WW Norton. London. pp. 92–93.

- ^ "Steps Along the Path". www.accesstoinsight.org. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Marcus Aurelius. Meditations. Gregory Hays (trans). Weidenfeld and & Nicolson. London. 2003 pp. 70, 75.

- ISBN 1-86064-022-2pp. 282–85

- ISBN 3-89500-400-6p. 294.

- ^ Azim Nanji. 'Islamic Ethics' in Singer P (ed). A Companion to Ethics. Blackwell, Oxford 1995. p. 108.

- ^ John B Noss. Man's Religions. The Macmillan Company, New York. 1968 Ch. 16 pp. 758–59

- ISBN 978-0-226-34686-1. Winner of Ralph Waldo EmersonPrize.

- ^ Tillich, Paul (1963). Morality and Beyond. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. p. 69.

- ISBN 978-0-664-25163-5.

the enemies who rise up in our conscience against his Kingdom and hinder his decrees prove that God's throne is not firmly established therein.

- ^ Ninian Smart. The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 376

- ^ Ninian Smart. The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 364

- ^ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale: If God Spare My Life. Abacus. London. 2003 pp. 249–50

- ^ Ninian Smart. The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 353

- ^ Guthrie D, Motyer JA, Stibbs AM, Wiseman DLJ (eds). New Bible Commentary 3rd ed. Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester. 1989. p. 905.

- ^ Robert Graves. The Greek Myths: 2 (London: Penguin, 1960). p. 380

- ISBN 1-57455-110-8paragraph 1778

- ^ Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press 1992. Gaudium and Spes 16. Cfr. Joseph Ratzinger, On Conscience, San Francisco: Ignatius Press 2007

- ^ "Whispers in the Loggia: "Jesus Always Invites Us. He Does Not Impose."". Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1782

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1790–91

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1792

- ^ Samuel Willard Crompton, "Thomas More: And His Struggles of Conscience" (Chelsea House Publications, 2006); Marc D. Guerra, 'Thomas More's Correspondence on Conscience', in: Religion & Liberty 10(2010)6 <https://acton.org/thomas-mores-correspondence-conscience>; Prof. Gerald Wegemer, "Integrity and Conscience in the Life and Thought of Thomas More" [21 aug. 2006]<http://thomasmoreinstitute.org.uk/papers/integrity-and-conscience-in-the-life-and-thought-of-thomas-more/>; http://sacredheartmercy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/A-Reflection-on-Conscience.pdf Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Newman, John Henry (1887). An essay in aid of a grammar of assent. Saint Mary's College of California. London : Longmans, Green.

- ^ "Newman Reader - Letter to the Duke of Norfolk - Section 5". www.newmanreader.org. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Harold H Schulweis. Conscience: The Duty to Obey and the Duty to Disobey. Jewish Lights Publishing. 2008.

- ^ Ninian Smart. The Religious Experience of Mankind. Collins. NY. 1969 pp. 395–400.

- ISBN 978-0-89885-364-3.

- ^ Gilkes, Peter (July 2004). "Masonic ritual: Spoilt for choice". Masonic Quarterly Magazine (10). Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ Manning Clark. The Quest for Grace. Penguin Books, Ringwood. 1991 p. 220.

- ^ Aylmer Maude. Introduction to Leo Tolstoy. On Life and Essays on Religion (A Maude trans) Oxford University Press. London. 1950 (repr) pxv.

- ^ JSTOR 1397536.

- ^ a b Nader El-Bizri. "Avicenna's De Anima between Aristotle and Husserl" in Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (ed) The Passions of the Soul in the Metamorphosis of Becoming. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Dordrecht 2003 pp. 67–89.

- ^ a b Henry Sidgwick. Outlines of the History of Ethics. Macmillan. London. 1960 pp. 145, 150.

- ^ a b Rurak, James (1980). "Butler's Analogy: A Still Interesting Synthesis of Reason and Revelation", Anglican Theological Review 62 (October) pp. 365–81

- ^ a b Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Ethics. Eberhard Bethge (ed.) Neville Horton Smith (trans.) Collins. London 1963 p. 24

- ^ May, L. (1983). "On Conscience". American Philosophical Quarterly. 20: 57–67.

- ISBN 90-277-2452-0pp. 3–15.

- PMID 788015.

- ISBN 978-0-7679-1581-6. 2005.

- ^ Childress JF. Appeals to Conscience. Ethics 1979; 89: 315–35.

- ^ Erich Fromm. Greatness and Limitations of Freud's Thought. Jonathan Cape, London. 1980. pp. 126–27.

- ^ Sigmund Freud. "The Cultural Super-Ego" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994

- ISBN 978-0-15-100369-3.

- ISBN 978-0-85683-248-2

- ^ Compare

ISBN 978-0-19-217775-9.

- ^ Milton Wessel. Science and Conscience. Columbia University Press, New York 1980

- ^ D'Arcy, Eric. Conscience and Its Right to Freedom. Sheed and Ward, New York 1961.

- ^ Eva Fogelman. Conscience & courage: rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. New York: Anchor Books, c1994

- ^ George Kateb. Hannah Arendt: politics, conscience, evil. Martin Robertson, Oxford. 1984.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche "The Origins of Herd Morality" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994

- ^ Jeremy Bentham. Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. (Burns JH and Hart HLA eds), Athlone Press. London. 1970 Ch 12 p. 156n.

- ISBN 0-14-018765-0. pp. 95, 103, 106, 116, 126.

- ^ Anonymous. "Wild Justice and Fair Play: Animal Origins of Social Morality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-452-28068-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7615-1808-2.

- ^ Gisela Kaplan. Australian Magpie: Biology and Behaviour of an Unusual Songbird. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood. 2004. pp. 83, 124.

- ^ Susan Greenfield. The Quest For Identity in the 21st Century. Sceptre. London. 2008 p. 223.

- ^ Richard Dawkins. The God Delusion. Bantam Press. London 2006 p. 215-216.

- ^ Tranel, D. 'Acquired sociopathy': the development of sociopathic behavior following focal brain damage. Prog. Exp. Pers. Psychopathol. Res. 1994; 285–311.

- ^ Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M. & Cohen, J. D. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron 2004; 44, 389–400.

- ^ Jorge Moll, Roland Zahn, Ricardo de Oliveira-Souza, Frank Krueger & Jordan Grafman. The Neural Basis of Human Moral Cognition Archived 22 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Vision Circle 10 October 2005 accessed 18 October 2009.

- ^ Libet B, Freeman A and Sutherland K (eds). The Volitional Brain: Towards a Neuroscience of Free Will. Imprint Academic. Thorverton. 2000.

- ^ AC Grayling. "Do We Have a Veto?" Times Literary Supplement. 2000; 5076 (14 July): 4.

- ^ Batthyany, Alexander: Mental Causation and Free Will after Libet and Soon: Reclaiming Conscious Agency. In Batthyany und Avshalom Elitzur. Irreducibly Conscious. Selected Papers on Consciousness, Universitätsverlag Winter Heidelberg 2009, pp.135ff

- ISBN 978-1-84821-101-8.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989.

- ^ Little, W, Fowler HW, Coulson J, Onions CT. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. 3rd ed. Vol 1 Clarendon Pres. Oxford. 1992. pp. 402–03.

- .

- ^ Peter Singer. Practical Ethics. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1993 pp. 292–95.

- ^ Peter Singer. Democracy and Disobedience. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1973. p. 94

- ^ Ninian Smart. The Religious Experience of Mankind. Collins. New York 1969 pp. 511–12.

- ^ ISBN 0-271-02070-9p. 34

- ^ Campbell Garnett A. "Conscience and Conscientiousness" in Feinberg J (ed) Moral Concepts. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1969 pp. 80–92

- ^ A.J. Arberry (transl.). The spiritual Physik of Rhazes (London, John Murray 1950).

- ^ Ninian Smart. The Religious Experience of Mankind. Collins. New York. 1969. pp. 511–12

- ISBN 978-0-19-954784-5

- ^ a b c Thomas Aquinas. "Of the Natural Law" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 pp. 247–49.

- ^ Saarinen, R. Weakness of the Will in Medieval Thought From Augustine to Buridan. Brill, Leiden. 1994

- ^ Brain Davies. The Thought of Thomas Aquinas. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1992

- ^ Thomas à Kempis. "The Imitation of Christ". Leo Sherley-Price (trans) Penguin Books. London. 1965 Bk II, ch. 6 On The Joys of a Good Conscience. p. 74.

- ^ Anonymous. The Cloud of Unknowing. Clifton Wolters (trans.) Penguin Books. London 1965 ch. 28 p. 88

- ^ John of Ruysbroeck. The Kingdom of the Lovers of God. Kegan Paul. London. 1919. ch. III pp. 14–15 and ch XLIII p. 214

- ^ Spinoza. Ethics. Everyman's Library JM Dent, London. 1948. Part 2 proposition 35. Part 3 proposition 11.

- ^ Spinoza. Ethics. Everyman's Library JM Dent, London. 1948. Part 4 proposition 59, Part 5 proposition 30

- ^ Roger Scruton. "Spinoza" in Raphael F and Monk R (eds). The Great Philosophers. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. London. 2000. p. 141.

- ^ Richard L Gregory. The Oxford Companion to the Mind. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 1987 p. 308.

- ^ Georg Hegel. Philosophy of Right. Knox TM trans, Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1942. para 137.

- ^ Joseph Butler "Sermons" in The Works of Joseph Butler. (Gladstone WE ed), Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1896, Vol II p. 71.

- ^ Henry Sidgwick. Outlines of the History of Ethics. Macmillan, London. 1960 pp. 196–97.

- ^ John Selden. Table Talk. Garnett R, Valee L and Brandl A (eds) The Book of Literature: A Comprehensive Anthology. The Grolier Society. Toronto. 1923. Vol 14. p. 67.

- ^ Arthur Schopenhauer. The World as Will and Idea. Vol 1. Routledge and Kegan Paul. London. 1948. pp. 387, 482. "I believe that the influence of the Sanskrit literature will penetrate not less deeply than did the revival of Greek literature in the 15th century." p xiii.

- ^ Kant I. "The Noble Descent of Duty" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 41.

- ^ Kant I. "The Categorical Imperative" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 274.

- ^ Kant I. "The Doctrine of Virtue" in Metaphyics and Morals. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1991. pp. 183 and 233–34.

- ^ John Plamenatz. Man and Society. Vol 1. Longmans. London. 1963 p. 383.

- ^ Hill T Jr "Four Conceptions of Conscience" in Shapiro I and Adams R. Integrity and Conscience. New York University Press, New York 1998 p. 31.

- ^ Roger Woolhouse. Locke: A Biography. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 2007. p. 53.

- ISBN 0-486-20530-4. Vol 1. ch II. pp. 71-72fn1.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan (Molesworth W ed) J Bohn. London, 1837 Pt 2. Ch 29 p. 311.

- ^ William Godwin. Enquiry Concerning Political Justice. Codell Carter K (ed), Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1971 Appendix III 'Thoughts on Man' Essay XI 'Of Self Love and Benevolence' p. 338.

- ^ Adam Smith. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Part III, section ii, Ch III in Rogers K (ed) Self Interest: An Anthology of Philosophical Perspectives. Routledge. London. 1997 p. 151.

- ^ a b John Stuart Mill. "Considerations on Representative Government". Ch VI. In Rogers K (ed) Self Interest: An Anthology of Philosophical Perspectives. Routledge. London. 1997 pp. 193–94

- ^ John K Roth (ed). The Philosophy of Josiah Royce. Thomas Y Crowell Co. New York. 1971 pp. 302–15.

- ^ Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Ethics. (Eberhard Bethge (ed) Neville Horton Smith (trans) Collins. London 1963 p. 242

- ^ a b Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Ethics. (Eberhard Bethge (ed) Neville Horton Smith (trans) Collins. London 1963 p. 66

- ^ Simon Soloveychik. Parenting For Everyone. Ch 12 "A Chapter on Conscience" Archived 16 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. 1986. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ Hannah Arendt. Crises of the Republic. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. New York. 1972 p. 62.

- ^ John Stuart Mill. "Utilitarianism" and "On Liberty" in Collected Works. University of Toronto Press. Toronto. 1969 Vols 10 and 18. Ch 3. pp. 228–29 and 263.

- ^ a b Hannah Arendt. The Life of the Mind. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1978. p. 191.

- ^ Hannah Arendt. The Life of the Mind. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1978. p. 190.

- S2CID 9421843.

- ^ Quoted in Gino Segre. Faust in Copenhagen: A Struggle for the Soul of Physics and the Birth of the Nuclear Age. Pimlico. London 2007. p. 144.

- ISBN 0-415-27101-0pp. 13 et seq.

- ^ Hellman, John. Simone Weil: An Introduction to Her Thought. Wilfrid Laurier, University Press, Waterloo, Ontario. 1982.

- ISBN 0-415-27101-0p. 13.

- ^ Charles Darwin. "The Origin of the Moral Sense" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 44.

- ^ Émile Durkheim. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. The Free Press. New York. 1965 p. 299.

- ^ AJ Ayer. "Ethics for Logical Positivists" in P Singer (ed). Ethics. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 151.

- ^ GE Moore. Principia Ethica. Cambridge University Press. London. 1968 pp. 178–79.

- ISBN 0-14-002967-2. p. 60

- ^ Michael Walzer. Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War and Citizenship. Clarion-Simon and Schuster. New York. 1970. p. 124.

- ^ Michael Walzer. Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War and Citizenship. Clarion-Simon and Schuster. New York. 1970. p. 131

- ^ Ronald Dworkin. Life's Dominion. Harper Collins, London 1995. pp. 239–40

- ^ Edward Conze. Buddhism: Its Essence and development. Harper Torchbooks. New York. 1959. pp. 20 and 46

- ^ Peter Singer. Democracy and Disobedience. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1973. p. 94.

- ^ David Chalmers. The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 1996 pp. 83–84

- ^ Nicholas Fearn. Philosophy: The Latest Answers to the Oldest Questions. Atlantic Books. London. 2005. pp. 176–177.

- ^ Roger Scruton. Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey. Mandarin. London. 1994. p. 271

- ISBN 0-241-14207-5pp. 87 and 102.

- ^ Jonathan Glover. I: The Philosophy and Psychology of Personal Identity. Penguin Books, London. 1988. p. 132.

- ^ a b Garrett Hardin, "The Tragedy of the Commons", Science, Vol. 162, No. 3859 (13 December 1968), pp. 1243–48. Also available here [1] and here.

- ^ Scott James Shackelford. 2008. "The Tragedy of the Common Heritage of Mankind". Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ISBN 0-88784-586-Xpp. 17, 81 and 172.

- ^ Alan Donagan. The Theory of Morality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 1977. pp. 131–38.

- ^ Beauchamp TL and Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. Oxford University Press, New York. 1994 pp. 478–79.

- ^ a b Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Lingis A (trans) Duquesne University Press, Pittsburgh, PA 1998. pp. 84, 100–01

- ^ ISBN 9780198854142.

- ^ Knafla LA. Conscience in the English Common Law Tradition. University of Toronto Law Journal 1976; 26:1–16

- ^ Jeremy Lee. Conscience Voting. Veritas Pub. Co. Morley, W.A. 1981.

- ISBN 0-14-018765-0. p. 293.

- ^ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A [XX1]. 16 December 1966 U.N.T.S. No. 14668, vol 999 (1976), p. 171.

- ^ Emily Miles. A Conscientious Objector's Guide to the UN Human Rights System Archived 15 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Quaker United Nations Office, Geneva & CONCODOC, London. 2000. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ a b c John Rawls. A Theory of Justice. Oxford University Press. London 1971. pp. 368–70

- ^ Peter Singer. Democracy and Disobedience. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1973. pp. 86–91

- ^ Peter Singer. Democracy and Disobedience. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1973 pp. 94–99.

- S2CID 145099462.

- ^ Henry David Thoreau. Civil Disobedience. 1848. reprinted Signet Classic, New York. 1960 pp. 228, 229, 236.

- ^ "Army Deserter Arrested at Border; Opposed Iraq War". ABC News. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Hayes D. Challenge of Conscience: The Story of the Conscientious Objectors. Allen & Unwin. London 1949.

- ^ For example see Jan Brabec, Václav Havel, Ivan Lamper, David Nemec, Petr Placak, Joska Skalnik et al. "Prisoners of Conscience". New York Review of Books. 1989; 36 (1) 2 February. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Katherine White. "Crisis of Conscience: Reconciling Religious Health Care Providers' Beliefs and Patients' Rights", Stanford Law Review 1999; 51: 1703–24.

- ISBN 0-8156-0276-6p. 208.

- ^ a b Dykhuizen, George. The Life and Mind of John Dewey. Southern Illinois University Press. London. 1978. p. 165

- ^ Walter Isaacson. Einstein: His Life and Universe. Simon and Schuster. New York. 2008. p. 414.

- ^ Life of Johnson. Oxford University Press. London. 1927 Vol. I 1709–1776. p. 505.

- ^ John Rawls. A Theory of Justice. Oxford University Press. London 1971. pp. 364–65.

- ^ Peter Singer. Democracy and Disobedience. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1973 p. 85.

- ISBN 0-691-02281-X

- ISBN 978-0-670-89160-3.

- ^ Greg Myre. "Israeli Army Bulldozer Kills American Protesting in Gaza". The New York Times, 17 March 2003. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ^ Michelle Nichols. "Gore urges civil disobedience to stop coal plants". Reuters. Wed, 24 September 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ "NASA Scientist Hansen Arrested at Tar Sands Protest - A Grim Sign of the Times | Jeff Goodell | Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. 11 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Bill McKibben. "The keystone pipeline revolt: why mass arrests are just the beginning". Rolling Stone. 28 September 2011. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-keystone-pipeline-revolt-why-mass-arrests-are-just-the-beginning-20110928 (accessed 29 December 2012)

- ^ Anti-coal protestors arrested in Little Rock. CBC news Mat y 6 2012 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/story/2012/05/05/bc-jaccard-coal-protest.html (accessed 29 December 2012)

- ^ "Nasa climate expert makes personal appeal to Obama". the Guardian. 2 January 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ James Hansen. Tell Barack Obama the Truth – The Whole Truth. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 10 December 2009. - ^ "Nature Climate Change". Nature. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "The Wallenberg Effect". The Journal of Leadership Studies. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ISBN 1-58430-157-0

- ^ University of Minnesota. Center from Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ISBN 0-375-40211-X

- ^ ""The White Rose Leaflets" Revolt & Resistance www.HolocaustResearchProject.org". www.holocaustresearchproject.org. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Sohn, LB (1982). "The new international law: Protection of the rights of individuals rather than states". American University Law Review. 32: 1.

- ^ S Milgram. Obedience to Authority. New York. 1974.

- ^ Bede Griffiths. A New Vision of Reality: Western Science, Eastern Mysticism and Christian Faith. Fount. London. 1992. p. 276.

- ^ William Thompson. Passages About the Earth: An Exploration of the New Planetary Culture. Rider and Co. London. 1974. Ch 7. 'To Findhorn and Lindisfarne' pp. 150–83.

- ^ P willets 'Introduction' in P. Willetts (ed) The Conscience of the World. The Influence of Non-Governmental Organizations in the UN System. Hurst & Co, London (1996) p. 11.

- ISBN 0-349-11112-Xp. 332.

- Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered. Abacus London. 1974. p. 112.

- ^ Edward Goldsmith. The Way. Shambhala, Boston. 1993. p. 64.

- ^ James Lovelock. Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1979 p. 123.

- ^ Geoff Davies. Economia: New Economic Systems to Empower People and Support the Living World. ABC Books. Sydney. 2004. pp. 202–03.

- ^ Cabrera, Luis. Political Theory of Global Justice: A Cosmopolitan Case for the World State. London, Routledge. 2006.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (15 May 2009). "Can 350.org save the world?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (25 September 2009). "Why 350 is the most important number on the planet | Opinion". the Guardian. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Editorial. "Microcredit Movement Tackling Poverty one Tiny Loan at a Time". San Francisco Chronicle. 3 October 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ Bob Brown. Memo For a Saner World. Penguin Books. Melbourne. 2004. pp. 12–13.

- ^ James Norman. Bob Brown: Gentle Revolutionary. Allen & Unwin. Sydney. 2004. p. 180.

- ^ Nick Lewer. Physicians and the Peace Movement. Frank Cass, London. 1992. pp. 78–80 and 107.

- ISBN 0-14-004461-2

- ISBN 0-465-02121-2

- ISBN 978-90-411-0505-9

- .

- ^ Peter Singer. One World: The Ethics of Globalisation. Text Publishing. Melbourne. 2002 p. 213.

- ^ Ninian Smart. Beyond Ideology: Religion and the Future of Western Civilisation. Collins, London. 1981. p. 313.

- ^ RW McChesney. "Introduction to Noam Chomsky". Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order. Seven Stories Press. New York. 1999. pp. 9–11.

- ^ John Passmore. The Perfectibility of Man. Duckworth, London. 1972. pp. 324–27.

- ^ US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Anonymous. "The Global Arms Trade: Strengthening International Regulations. Interview with Oscar Arias Sanchez". Harvard International Review. 1 July 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2010

- ^ Jonathan Allen. "Tibet challenges world conscience, U.S. Speaker says". Reuters. Fri, 21 March 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ "How Mandela shaped the conscience of the world". Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Right Livelihood Award. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Greenpeace. Press Release Archived 16 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine. 13 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ Mu Xuequan. "Alternative Nobel awards go to Congo, New Zealand, Australia" Archived 17 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine. www.chinaview.cn 2009-10-13 22:35:19. Retrieved 18 October 2009

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (2 March 2012). "Avaaz faces questions over role at centre of Syrian protest movement". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Dick Jones. "The Pedder Tragedy" in Roger Green: Battle for The Franklin. Fontana. ACF. Sydney 1981 p. 53

- ^ Chinua Achebe, G.F. Michelsen, Ben Okri, Harold Pinter, Norman Rush, Susan Sontag et al. "The Case of Ken Saro-Wiwa". New York Review of Books. Volume 42, Number 7 · 20 April 1995 accessed 17 October 2009.

- ^ Pico Iyer. "The Unknown Rebel: with a single act of defiance, a lone Chinese hero revived the world's image of courage". Time. 13 April 1998. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ Henry P Van Dusen. Dag Hammarskjöld: A Biographical Interpretation of Markings. Faber and Faber London. 1967

- ^ Trent Angers. The Forgotten Hero of My Lai: The Hugh Thompson Story. Acadian House Publishing, 1999

- ^ Ben Hills. The Hilton Fiasco. SMH 12 February 1998, p. 11 "Articles". Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012. (Retrieved 6 September 2010)

- ^ "SOVIETS CLOSE TO USING A-BOMB IN 1962 CRISIS, FORUM IS TOLD". www.latinamericanstudies.org. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Sanburn, Josh (20 January 2011). "A Brief History of Self-Immolation". Time. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011.

- PMID 9641922.

- ^ Marie Brenner. "The Man Who Knew Too Much". Vanity Fair. May 1996.

- ^ "Whistler-Blower Guardians Say FDA Officials Tried to Undermine Critic". San Francisco Chronicle. 24 November 2004

- ^ Andrew Revkin. "Bush Aide Softened Greenhouse Gas Links to Global Warming". The New York Times. 8 June 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ "Iraqi shoe-throwing reporter becomes the talk of Iraq". Reuters. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ISBN 1-85424-129-X

- ^ Hurst, Mike (7 October 2006). "Peter Norman's Olympic statement". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ "50 stunning Olympic moments No13: Tommie Smith and John Carlos salute | Simon Burnton". the Guardian. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ISBN 0-399-11904-3)

- ^ Jones JH. "The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment" in Emanuel EJ et al. The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 2008. pp. 86–96 at 94.

- ^ Martin Khor. "Gaza, under attack again, a stain on world's conscience" Archived 3 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Third World Network. Tuesday, 4 March 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-8225-4931-4.

- ^ James Bone. "Sacked envoy Peter Galbraith accuses UN of 'cover-up' on Afghan vote fraud". The Times. 1 October 2009.

- ^ Neely Tucker. "A Web of Truth. Whistle-Blower or Troublemaker, Bunny Greenhouse Isn't Backing Down". The Washington Post. Wednesday, 19 October 2005

- ^ "On This Day 1950–2005, 22 July, 1987: Cartoonist shot in London street". BBC. 22 July 1987.

- ISBN 0-226-67432-0

- ^ Natalya Estemirova: "I'm sure that human rights defenders are murdered on authorities' blessing", Vyacheslav Feraposhkin, Caucasian Knot, Memorial, 15 July 2009

- ^ Tait, Robert and Weaver, Matthew (22 June 2009). "How Neda Soltani became the face of Iran's struggle". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Scott MacLeod. "Shirin Ebadi: For Islam and Humanity". Time. 26 April 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2009

- ^ Schiller, Bill (10 April 2010). "'Conscience of China' comes home". The Star. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ McKey, Robert (8 October 2010) Jailed Chinese Dissident's 'Final Statement', The New York Times accessed 8 November 2010

- ^ Margarette Driscoll (14 November 2010). "Dying in agony: his reward for solving a $230 million fraud". The Sunday Times. http://www.justiceforsergei.com/download.php?id=16 (accessed 29 December 2012)

- ^ David Leser. Children Overboard. Two Women, Two Stories. WW 2007; August: pp. 76–82 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (Retrieved 26 July 2011). - ^ Synovitz, Ron (12 October 2012). "Malala Yousafzai, the Girl Shot by the Taliban, Becomes a Global Icon". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- CNN-IBN. Archived from the originalon 31 December 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ "India's collective conscience is finally stirred". Arab News. 1 January 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Edward Snowden: the whistleblower behind the NSA surveillance revelations". the Guardian. 11 June 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Edward Snowden: I Acted To Protect 'Basic Liberties'". HuffPost. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ Vyasa (Kamala Subramaniam abr.). Mahabharata. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay. 1989. pp. 430–32

- ^ Vyasa (Kamala Subramaniam abr.). Mahabharata. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay. 1989. p. 742.

- ^ Michel de Montaigne. Essays. Cohen JM (trans.) Penguin Books. Ringwood. 1984. p. 397.

- ^ Matsuo Bashō. (Yuasa N (trans.) Narrow Road to the Deep North. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth. 1966. p. 118.

- ^ Geoffrey Chaucer. The Franklin's Prologue and Tale (Spearing AC intro.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1997. p. 42.

- ^ AC Bradley. Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. Macmillan and Co. London. 1937. pp. 97–101

- ^ AC Bradley. Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. Macmillan and Co. London. 1937 p. 99.

- ^ Manning Clark. A Discovery of Australia: 1976 Boyer Lectures. Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney. 1976. p. 37.

- ^ Joan Bennett. Five Metaphysical Poets. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1971. p. 33.

- ^ Stephen Grecco. "A physician healing himself: Chekhov's treatment of doctors in the major plays" in ER Peschel (ed). Medicine and Literature (1980) pp. 3–10.

- ^ Anton Chekhov. Selected Stories (J Coulson, trans.) Oxford University Press. London. 1963 p. 249.

- ^ Anton Chekhov. The Island: A Journey to Sakhalin (L and M Terpak trans) Century. London 1987 p. ix.

- ^ EH Carr. Dostoevsky. 1821–1881. Unwin Books. London. 1962 pp. 147–52.

- ^ Ralph Freedman. Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis. Jonathan Cape, London 1978. pp. 233–37.

- ^ Paul Kocher. Master of Middle Earth: The Achievement of JRR Tolkien. Thames and Hudson, London. 1973. p. 120.

- ^ Conor Cruise O'Brien. Camus. Fontana/Collins. London 1970 p. 84.

- ^ At Your Library 'To Kill a Mockingbird http://atyourlibrary.org/culture/kill-mockingbird-world-needs-him-now-atticus-finch-continues-inspire accessed 3 November 2012

- ^ Robert Bolt. A Man For All Seasons: A Play of Sir Thomas More. Heinemann. London 1961 p. 92.

- ISBN 0-434-69517-3pp. 469–73.

- ^ George Orwell. Nineteen Eighty-Four. Penguin Books, Ringwood. 1974. pp. 214–15, 216

- ISBN 978-0-520-25007-9

- ^ Albert Tucker. Man's Head. National Gallery of Australia. Accn No: NGA 82.384. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ISBN 0-14-044674-5. p. 54.

- ^ Ingmar Bergman. The Seventh Seal. Touchstone. New York. 1960 p. 146

- ^ Aljean Harmetz. Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Making of Casablanca. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. London. 1992.

- ^ Robert Bolt. Doctor Zhivago (screenplay). Collins and Harvill Press. London. 1965 p. 217

- Doppelganger" in Judith B. Kerman (ed). Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Bowling Green State University Popular Press. Bowling Green, Ohio. 1991 p. 4 at 6.

- ^ J.S. Bach. Messe H-Moll/Mass in B minor BWV 232. Balthasar-Neumann-Choir. Freiburger Barockorchester. Thomas Hengelbrock. BMG Music. 1997.

- ^ Christoph Wolff. Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 2000. pp. 8, 339, 438–42.

- ^ JWN Sullivan. Beethoven: His Spiritual Development. George Allen & Unwin, London. 1964 p. 120.

- ^ Ludwig van Beethoven. The Late Quartets Vol II. String Quartet in A minor, Op. 132. Quartetto Italiano. Phillips Classics Productions 1996.

- ^ Ben Urish and Kenneth G. Bielen. The Words and Music of John Lennon. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2007 pp. 99–100.

- ISBN 0-8118-3793-9p. 118.

- ^ James Schofield Saeger. The Mission and Historical Missions: Film and the Writing of History. The Americas. 1995; 51(3):393–415.

- ^ Al Weisel, "Deep Forest's Lush Lullaby", Rolling Stone, 21 April 1994, 26

- ^ Dream Academy. 'Forest Fire'. Lyrics "The Dream Academy - Forest Fire Lyrics". Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2012. (accessed 7 December 2012)

- ^ Valk, Elizabeth P. (24 February 1992). "From the Publisher". Time. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

External links

The dictionary definition of conscience at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of conscience at Wiktionary Quotations related to Conscience at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Conscience at Wikiquote