Eppa Hunton Jr.

Eppa Hunton Jr. | |

|---|---|

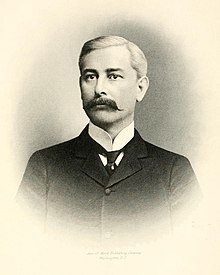

Portrait of Hunton, c. 1915 | |

| Born | Eppa Hunton III April 14, 1855 Brentsville, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | March 5, 1932 (aged 76) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Burial place | Hollywood Cemetery |

| Education | University of Virginia (LLB) |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2, including Eppa IV |

| Parent |

|

| Signature | |

Eppa Hunton III (April 14, 1855 – March 5, 1932), known as Eppa Hunton Jr., was an American lawyer, railroad executive, and politician. The son of General Eppa Hunton, he experienced a turbulent childhood with the American Civil War and Reconstruction as its backdrop. After graduating from the University of Virginia School of Law, he practiced law with his father in Warrenton, Virginia, for a number of years before moving south to Richmond in 1901 to help found the law firm Munford, Hunton, Williams & Anderson (now Hunton Andrews Kurth).

He served as

Early life and family

Childhood and education

Hunton was born on April 14, 1855, in

In March 1862, the Confederate Army evacuated northern Virginia to fight the

After the war, Hunton and his family moved to Warrenton, Virginia, where he attended private boarding schools. His father won election to the United States House of Representatives in 1872. Hunton was sent away to attend the Bellevue High School in Bedford County, followed by the University of Virginia School of Law, where he joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity and studied under John B. Minor. He graduated with a Bachelor of Laws in 1877.[2][3] Mere months earlier, congressional leaders agreed that the Electoral Commission (on which Hunton's father was the sole Southern member) would be allowed certify the election of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to the presidency, in exchange for the withdrawal of the last federal troops from the South, ending the Reconstruction era.[7][2]

Marriages

Hunton married the former Minerva Winston "Erva" Payne, the eldest daughter of General William H. F. Payne, at St. James' Episcopal Church in Warrenton on November 18, 1884.[8] The couple then took a train north for their honeymoon.[9] Erva suffered from poor health, and, despite Hunton's efforts over the succeeding years to get her medical help, she died on October 9, 1897.[10] Pallbearers at her funeral included Charles Minor Blackford, Henry Halleck, Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee Jr. and Joseph E. Willard.[11] No children were born from the marriage.[4]

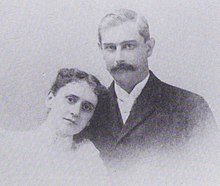

On April 24, 1901, Hunton married the former Virginia Semmes Payne, a younger sister of Erva, at St. James' Church in a wedding attended by many of the state's social and political elites.

Career

Law

Hunton was admitted to the Virginia bar upon his graduation from law school in 1877. He practiced law with his father in Warrenton under the name Hunton & Son for the next 25 years, living at Brentmoor with his parents for most of this period. During his first few years as an attorney, Hunton worked to rebuild the practice his father had neglected after his election to Congress. Shortly after his father retired from Congress in 1881, the two concluded that there was not enough work in the area for the both of them and that the younger Hunton would continue to work in Warrenton while the elder Hunton would open up an office in Washington, D.C.[6][14]

In 1901, while he was in Richmond as a member of the state's constitutional convention, Hunton was approached by the young lawyers E. Randolph Williams and Henry W. Anderson. Williams's law partner, William Wirt Henry, had died a few months before, and Anderson's, Beverley B. Munford, was suffering from ill health. Williams and Anderson proposed the creation of a new firm, modeled after the large, full-service firms of New York City, with Munford and Hunton at the helm as senior partners. After consulting with his father and meeting with his three partners in Washington in September, Hunton agreed to make his move to Richmond permanent, and Munford, Hunton, Williams & Anderson was officially formed on November 1, 1901.[4][6][14][15]

With his fellow senior partner ill, eventually dying of

Politics

A member of the

In early 1901, Hunton announced his intention to seek the Democratic nomination to the Fauquier County seat in the state constitutional convention to be held that June.[27] He successfully challenged commonwealth's attorney James P. Jeffries, the choice of T. C. Pilcher's county political machine, in the party primary election and was nominated by acclamation at the succeeding convention.[4][28][29] He defeated Republican W. K. Skinker in May in a race that was closer than expected.[30] The constitutional convention was called for two primary reasons: to disenfranchise black voters after the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments and to curb the influence of corporations in state politics. In a speech delivered on securing the Democratic nomination, Hunton himself expressed his support for taking back suffrage from "ignorant" black voters.[14][31] At the convention, he would later state that the participation of corporations in Virginia politics “ha[d] been demoralizing and debauching second only to the presence of the negro vote in the electorate”.[32]

On taking his seat, Hunton led the so-called "independent Democrats" in supporting John Goode for convention president over establishment favorite John W. Daniel.[33][34] After Daniel declined to stand for the position, Goode won and appointed Hunton chair of the convention's Judiciary Committee. In this role, Hunton proposed the elimination of Virginia's county court system, in an effort to weed out local corruption.[35] He would go on to vote for the adoption of the new constitution without a statewide referendum.[14] After the convention, he expressed to his father his lack of interest in a political future, though he would continue to take stands on certain issues, such as his opposition to state alcohol prohibition laws during the 1910s.[4][36]

Civic life

Hunton was a leading Richmond society figure during his three decades in that city. He was long associated with the

Hunton was also a member of the

Later life and death

On September 16, 1920, Hunton was elected president of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad by its board of directors, and he retired from Munford, Hunton, Williams & Anderson the same day. Taking up an office in Richmond's Broad Street Station, he succeeded the late William H. White, under whom he had served as the railroad's general counsel since 1914.[46] Chief among Hunton's accomplishments as president was the establishment of a Voluntary Relief Department that allowed railroad employees to save a portion of their salary to go towards supporting their family after their death.[47]

Hunton died on March 5, 1932, at his residence, 810 West Franklin Street, in Richmond. He had suffered from a heart affliction for over a year but was only seriously ill for a few days. Following services at St. Paul's Church, he was buried in Hollywood Cemetery alongside his parents, his first wife, and his daughter.[1] His estate was valued at $880,000 (equivalent to $19,651,902 in 2023). In his will, he left over $500,000 to his widow, $250,000 to his son, $10,000 to MCV, and $5,000 to St. Paul's Church; he also established a $50,000 trust fund to be used to aid Richmond's neediest residents.[48]

In 1939, MCV announced that its new dormitory at 12th and Marshall Streets, which had opened the previous year, would be named Hunton Hall in recognition of Hunton's years of service and financial contributions to the school.[49] The building was demolished in 1977.[50] In 1989, Virginia Commonwealth University named the First Baptist Church building Hunton Hall (now the Hunton Student Center) for Hunton and his son, who succeeded him on the MCV board of visitors.[51]

Hunton's

In 1999, he was named by Style Weekly as one of the 100 most influential Richmonders of the previous century.[45]

References

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c History of Virginia. Vol. 5. Chicago/New York: American Historical Society. 1924. pp. 2–4. Retrieved January 26, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Men of Mark in Virginia: Ideals of American Life. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Men of Mark Publishing Co. 1906. pp. 306–308. Retrieved October 8, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hunton, Eppa (1933). Autobiography of Eppa Hunton. Richmond: William Byrd Press. pp. 9–23, 63–64, 134–137, 227–235. Retrieved August 16, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Bible of Virginia Weirs" (PDF). Manassas Journal. February 13, 1913. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ .

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann (1951). Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 169–171, 200–202. Retrieved August 6, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Gay, Thomas B. (1971). The Hunton Williams Firm and Its Predecessors, 1877–1954. Vol. 1. Richmond: Lewis Printing Company. pp. 1–12, 51–54.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ George, Charles E., ed. (August 1916). "Personal Sketches: Hon. Eppa Hunton Jr". The Lawyer and Banker and Southern Bench and Bar Review. Vol. 9, no. 4. New Orleans, Louisiana. p. 259. Retrieved April 6, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- .

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pulley, Raymond H. (1968). Old Virginia Restored. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. p. 95. Retrieved October 17, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- .

- ^ Ferrell, Henry C. Jr. (1966). Prohibition, Reform, and Politics in Virginia, 1895-1916. p. 232. Retrieved April 6, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Written at Richmond, Virginia. "Funeral Will Be Today For Eppa Hunton Jr". The Washington Post. No. 20353. Washington, D.C. Associated Press. March 7, 1932. p. 10. Retrieved October 9, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Corks & Curls. Vol. 46. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. 1933. p. 10. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- A. N. Marquis Company (published 1930). 1930–31. p. 1169. Retrieved October 8, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The 100 most influential Richmonders of the century". Style Weekly. Vol. 17, no. 20. Richmond, Virginia. May 19, 1999. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ "Railway Officers". Railway Age. Chicago, Illinois. October 1, 1920. p. 593. Retrieved October 8, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Voluntary Relief Department Was Pride of Mr. Hunton". R. F. & P. Monthly Bulletin. Vol. 1, no. 7. Richmond, Virginia. April 1932. p. 5. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lepley, Pamela DiSalvo (January 25, 2007). "Hunton Student Center grand reopening honors VCU's history". VCU News. Retrieved October 3, 2022.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: West Franklin Street Historic District" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. January 1972. p. 1A. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hunton House". Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

External links

Media related to Eppa Hunton Jr. at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eppa Hunton Jr. at Wikimedia Commons- Eppa Hunton Jr. at the Virginia House of Delegates

- Eppa Hunton Jr. at Find a Grave