Joe Hill (activist)

Joe Hill | |

|---|---|

Labor activist, songwriter, and member of the Industrial Workers of the World | |

| Signature | |

|

Joe Hill (October 7, 1879 – November 19, 1915), born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund and also known as Joseph Hillström,

In 1914, John G. Morrison, a Salt Lake City area grocer and former policeman, and his son were shot and killed by two men.[7] The same evening, Hill arrived at a doctor's office with a gunshot wound, and briefly mentioned a fight over a woman. He refused to explain further, even after he was accused of the grocery store murders on the basis of his injury. Hill was convicted of the murders in a controversial trial. Following an unsuccessful appeal, political debates, and international calls for clemency from high-profile figures and workers' organizations, Hill was executed in November 1915. After his death, he was memorialized by several folk songs. His life and death have inspired books and poetry.

The identity of the woman and the rival who supposedly caused Hill's injury, though frequently speculated upon, remained mostly conjecture for nearly a century. William M. Adler's 2011 biography of Hill presents information about a possible alibi, which was never introduced at the trial.[8] According to Adler, Hill and his friend and countryman Otto Appelquist were rivals for the attention of 20-year-old Hilda Erickson, a member of the family with whom the two men were lodging. In a recently discovered letter, Erickson confirmed her relationship with the two men and the rivalry between them. The letter indicates that when she first discovered Hill was injured, he explained to her that Appelquist had shot him, apparently out of jealousy.[9]

Early life

Joel Emmanuel Hägglund was born 1879 in Gävle (then spelled Gefle), a city in the province of Gästrikland, Sweden. He was the third child in a family of nine, where three children died young. His father, Olof, worked as a conductor on the Gefle-Dala railway line.[10] Olof (1846–1887) died at the age of 41, and his death meant economic disaster for the family. Joe's mother Margareta Catharina (1844–1902) did, however, succeed in keeping the family together until she died when Joel was in his early twenties.

The Hägglund family home still stands in Gävle at the address Nedre Bergsgatan 28, in Gamla Stan, the Old Town. As of 2011[update] it houses a museum and the Joe Hill-gården, which hosts cultural events.

In his late teens-early twenties, Joel fell seriously ill with skin and glandular tuberculosis, and underwent extensive treatment in Stockholm. In October 1902, when nearly 23, Joel and his brother Paul Elias Hägglund (1877–1955) emigrated to the United States. Hill became an itinerant laborer, moving from New York City to Cleveland, and eventually to the west coast. He was in San Francisco at the time of the 1906 earthquake.[11]

IWW

By this time using the name Joe or Joseph Hillstrom (possibly because of anti-union blacklisting), he joined the

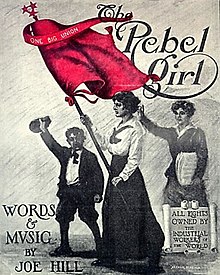

Hill rose in the IWW organization and traveled widely, organizing workers under the IWW banner, writing political songs and satirical poems, and making speeches. He and Harry McClintock were Spellbinders for the IWW and would show up as they did at the Tucker Utah strike on June 14, 1913 (Salt Lake Tribune). He shortened his pseudonym to "Joe Hill" as the pen-name under which his songs, cartoons and other writings appeared. His songs frequently appropriated familiar melodies from popular songs and hymns of the time. He coined the phrase "pie in the sky", which appeared in his song "The Preacher and the Slave" (a parody of the hymn "In the Sweet By-and-By"). Other songs written by Hill include "The Tramp", "There Is Power in a Union", "The Rebel Girl", and "Casey Jones—the Union Scab".

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

Trial

As an itinerant worker, Hill moved around the west, hopping freight trains, going from job to job. By the end of 1913, he was working as a laborer at the Silver King Mine in Park City, Utah, not far from Salt Lake City.

On January 10, 1914, John G. Morrison and his son Arling were killed in their Salt Lake City grocery store by two armed intruders masked in red

The prosecution, for its part, produced a dozen eyewitnesses who said that the killer resembled Hill, including 13-year-old Merlin Morrison, the victims' son, and a brother, who upon first seeing Hill said, "That's not him at all" but later identified him as the murderer. The jury took just a few hours to find him guilty of murder.[12]

An appeal to the Utah Supreme Court was unsuccessful. Orrin N. Hilton, the lawyer representing Hill during the appeal, declared: "The main thing the state had on Hill was that he was a Wobbly and therefore sure to be guilty. Hill tried to keep the IWW out of [the trial] ... but the press fastened it upon him."[12]

In a letter to the court, Hill continued to deny that the state had a right to inquire into the origins of his wound, leaving little doubt that the judges would affirm the conviction. Chief Justice Daniel Straup wrote that his unexplained wound was "a distinguishing mark", and that "the defendant may not avoid the natural and

The case turned into a major media event. President Woodrow Wilson, Helen Keller (the blind and deaf author and fellow-IWW member), the Swedish ambassador and the Swedish public all became involved in a bid for clemency. It generated international union attention, and critics charged that the trial and conviction were unfair. Despite the various petitions the governor at the time William Spry maintained Hill's guilt. More recently, Utah Phillips considered Hill to have been a political prisoner who was executed for his political agitation through songwriting.[15]

In a biography published in 2011, William M. Adler concludes that Hill was probably innocent of murder, but also suggests that Hill came to see himself as worth more to the labor movement as a martyr than he was alive, and that this understanding may have influenced his decisions not to testify at the trial and subsequently to spurn all chances of a pardon.[16] Adler reports that evidence pointed to early police suspect Frank Z. Wilson, and cites Hilda Erickson's letter, which states that Hill had told her he had been shot by her former fiancé.[8]

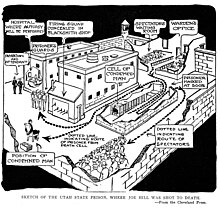

Execution

Hill was executed by firing squad on November 19, 1915, at Utah's Sugar House Prison. When Deputy Shettler, who led the firing squad, called out the sequence of commands preparatory to firing ("Ready, aim,") Hill shouted, "Fire—go on and fire!"[17]

That same day, a dynamite bomb was discovered at the

Just prior to his execution, Hill had written to Bill Haywood, an IWW leader, saying, "Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize ... Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don't want to be found dead in Utah."[12][19] Hunter S. Thompson asserted that Joe's last words were "Don't mourn. Organize."[20]

His last will, which was eventually set to music by Ethel Raim, founder of the group The Pennywhistlers, requested a cremation and reads:[21]

My will is easy to decide

For there is nothing to divide

My kin don't need to fuss and moan

"Moss does not cling to rolling stone"

My body? Oh, if I could choose

I would to ashes it reduce

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again.

This is my Last and final Will.

Good Luck to All of you

Joe Hill

Aftermath

Hill's body was sent to Chicago, where it was cremated; in accordance with his wishes, his ashes were placed into 600 small envelopes and sent around the world to be released to the winds. Delegates attending the Tenth Convention of the IWW in Chicago received envelopes November 19, 1916, one year to the day of Hill's execution (and not on May Day 1916 as Wobbly lore claims).[22][page needed] The rest of the 600 envelopes were sent to IWW locals, Wobblies and sympathizers around the world on January 3, 1917.[23][page needed]

In 1988, it was discovered that an envelope had been seized by the

After some negotiations, the last of Hill's ashes (but not the envelope that contained them) was turned over to the IWW in 1988. The weekly

One small packet of ashes was scattered at a 1989 ceremony which unveiled a monument to six unarmed IWW coal miners buried in Lafayette, Colorado, who had been machine-gunned by Colorado state police in 1927 in the Columbine Mine massacre. Until 1989 the graves of five of these men were unmarked. Another Wobbly, Carlos Cortez, scattered Hill's ashes on the graves at the commemoration.[26]

On the night of November 18, 1990, the Southeast Michigan IWW General Membership Branch hosted a gathering of "wobs" in a remote wooded area at which a dinner, followed by a bonfire, featured a reading of Hill's last will, "and then his ashes were released into the flames and carried up above the trees. ... The next day ... one wob collected a bowl full of ashes from the smoldering fire pit."[27] At that event several IWW members consumed a portion of Hill's ashes before the rest was consigned to the fire.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Hill's execution, Philip S. Foner published a book, The Case of Joe Hill, about the trial and subsequent events, which concludes that the case was a miscarriage of justice.[28]

Archival materials and legacy

Hill's handwritten last will and testament was uncovered in the first decade of the 21st century by archivist

Additional archival materials were donated to the

Influence and tributes

- Hill's exhortation, "Don't waste any time mourning. Organize!", often shortened to "Don't mourn—organize!", has become a widely used slogan of the political Left, especially after a defeat or death.

- Hill was memorialized in a tribute poem written about him c. 1930 by better source needed] Hayes gave a copy of his poem to fellow camp staffer Robinson, who wrote the tune in 40 minutes.[33]

- Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band opened their concert in Tampa, Florida, with the song.

- An eponymous opera by Alan Bush was premiered in Berlin in 1970 and later broadcast by BBC Radio 3.

- The Swedish socialist leader Ture Nerman(1886–1969) wrote a biography of Joe Hill. For the project, Nerman did the first serious research about Hill's life story, including finding and interviewing Hill's family members in Sweden. Nerman, who was a poet himself, also translated most of Hill's songs into Swedish.

- Ralph Chaplin wrote a tribute poem/song called "Joe Hill"[34] and referred to him in his song "Red November, Black November".

- Phil Ochs wrote and recorded a different, original song called "Joe Hill",[35] using a traditional melody found in the song "John Hardy", which tells a much more detailed story of Joe Hill's life and death.

- Singer/songwriter Josh Joplin wrote and recorded a song entitled Joseph Hillstrom 1879–1915 as a tribute to Joe Hill for the self-titled debut album Among the Oak & Ash of his band.

- In 1990, Smithsonian Folkways released Don't Mourn — Organize!: Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill. The compilation album featured the likes of Harry "Haywire Mac" McClintock, Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson, and Entertainment Workers IU630 I.W.W. performing Hill's songs, Billy Bragg and Si Kahn, and narrative interludes from Utah Phillips and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

- In 1990, Billy Bragg released his song "I Dreamed I Saw Phil Ochs Last Night", set to the melody of "I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night", on his EP The Internationale.

- Wallace Stegner published a fictional biography called Joe Hill in 1950.

- Authors Stephen and Tabitha King named their second child Joseph Hillstrom King, after Joe Hill.[36]

- Gibbs M. Smith wrote a biography, Joe Hill, later adapted for the 1971 movie Tempo Books was written by John McDermott, under that byline, although, as a mainstream novelist, he had been previously known only by his pen name, J. M. Ryan.

- A chapter of 1919is a stylized biography of Joe Hill.

- Thomas Babe's 1980 full-length play Salt Lake City Skyline retells the story of Joe Hill's trial.[38]

- "Calling Joe Hill" by Ray Hearne is frequently performed by Roy Bailey, a British socialist folk singer.

- In 1995, the first "Raise Your Banners" festival of political song was held in Sheffield, inspired by the 80th anniversary of the death of Joe Hill. Sheffield Socialist choir which was formed in 1988 organised the event and performed an arrangement by Nigel Wright of the Earl Robinson song about Joe Hill. Since then the festival has been held roughly every two years.[39]

- In 1980, Postverket, the Swedish postal service, issued a Joe Hill postage stamp. Red on a white background with the lyrics in English "We'll have freedom, love and health/When the grand red flag is flying, In the Workers' Commonwealth." The stamp cost SKr 1,70 which was the amount for airmail to the United States.[40]

- In 2003, on the album Blackout, Dropkick Murphys performed a song quoting the beliefs of Joe Hill and using the phrase "pie in the sky". The song was titled "Worker's Song" and was composed by Ed Pickford. It was also performed by Dick Gaughan, Scottish folk singer and socialist.[41]

- Chumbawamba's song about Joe Hill, "By and By", appears on the 2005 album A Singsong and a Scrap. It incorporates the first stanza of Alfred Hayes' poem and is set to substantially the same melody as "The Preacher and the Slave".

- Track three on Mickey Hart's Mystery Box CD (2008) titled "Down The Road" makes reference to Joe Hill.[42]

- Seattle composer and bandleader Wayne Horvitz created a musical tribute to Joe Hill in 2008. Joe Hill: 16 Actions for Orchestra, Voice and Soloist, which premiered at Meany Hall in Seattle, features the Northwest Sinfonia and guest soloists Bill Frisell, Robin Holcomb, Danny Barnes, and Rinde Eckert.

- Singer-songwriter Justin Townes Earle's 2009 song "They Killed John Henry" references folk heroes such as John Henry and contains a verse about Joe Hill.

- Otis Gibbs made the Joe Hill's Ashes album in 2010.

- Folk Punk Band Mischief Brew's song "Nevada City Serenade" in the 2011 Album The Stone Operation, vaguely references Joe Hill in its lyrics.

- In October 2011, activist/songwriter Si Kahn's one-man play Joe Hill's Last Will, featuring Hill's catalogue of songs and starring singer John McCutcheon, was produced by Main Stage West in Sebastopol, California.[43] The one-person musical was performed by McCutcheon several times, including a show in Salt Lake City on November 19, 2015, the 100th anniversary of Joe Hill's death. The centennial event was recorded on video and audio.

- In 2012, Anti-Flag released The General Strike, an album including a song titled "1915" telling the story of Joe Hill.

- In 2013, trombonist Roswell Rudd recorded a four-movement tribute to Joe Hill with the NYC Labor Chorus and others as part of his Trombone for Lovers album.[44]

- In 2014, Finnish rap-artist Paleface referenced "Joel Hägglund's ashes" in his song "Mull' on lupa" (I Have a Permit/I Am Allowed).

- In 2016, Shelby Bottom Duo released the CD Joe Hill Roadshow as a companion to their multimedia presentation A Musical History of Joe Hill and the Early Labor Movement.

- In 2019 Joe Hill is a minor character in the novel Deep River by Karl Marlantes.

See also

Works cited

- Adler, William M. (August 31, 2011). The Man Who Never Died: The Life, Times, and Legacy of Joe Hill, American Labor Icon. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60819-285-4.

- Davidson, Jared (2011). Remains to be Seen: Tracing Joe Hill's ashes in New Zealand. Wellington: Rebel Press. ISBN 978-0-473-18927-3.

- ISBN 0-06-093731-9.

References

- ^ "Joehill.org". Joehill.org. November 19, 1915. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Adler 2011, pp. 92–94, 121.

- ^ Adler 2011, pp. 115–119.

- ^ Harry McClintock (2004). Long Haired Preacher (Preacher and the Slave) – via YouTube.

- ^ Adler 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Adler 2011, pp. 12–13, 206.

- ^ Adler 2011, pp. 44–52.

- ^ ProQuest 885453470.

His [William Adler's] research is just incredible -- it expands what we know in really dramatic ways," said John R. Sillito, co-author of a new book on radicalism in Utah and a retired archivist at Weber State University in Ogden. "It builds a strong case that Wilson should have been the prime suspect.

- ^ Adler 2011, pp. 294–297.

- ^ "Joe's bio". The Joe Hill Project. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- OCLC 1039093111.

- ^ H2G2. February 19, 2002. Archived from the originalon March 29, 2005.

- ^ "Chief Justice Daniel N. Straup". KUED. June 25, 1914. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Joe Hill, Appeal to Reason, August 15, 1915; cited in "Joe Hill: Murderer or Martyr?"

- ^ Phillips, Utah (February 2005). Utah Phillips covers Joe Hill's "Pie in the Sky" "The Preacher and the Slave" (Speech). Live at the Rose Wagner Theater. Salt Lake City. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021.

- ^ "Songwriter shot dead". The Economist. August 6, 2011.

- ^ Hickerson, Joe (December 2, 2010). "Joe's Last Will". Labor Notes. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ "Dynamite Bomb For J.D. Archbold". The New York Times. November 22, 1915.

- ^ Zinn 2001, p. 335.

- ISBN 9780345301130.

- ^ Hill, Joe (November 18, 1915). – via Wikisource. [scan

]

]

- ^ "Joe Hill's Ashes Divided". The New York Times. November 20, 1916. p. 22. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Davidson 2011.

- ^ Jeff Ditz, "Drinking Joe Hill’s Ashes, "Fifth Estate", 2005.

- ^ "Episode 29: Billy Bragg (Part 1)". Thanks for Giving a Damn with Otis Gibbs. Episode 29. April 23, 2013.

- ^ Denver Post. June 11, 1989.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Landry, Carol (December 1990). "Joe Hill's Wake". Industrial Worker. p. 6.

- ISBN 978-0-7178-0022-3..

- ^ a b Shapiro, Gary (August 23, 2012). "Michael Nash, Record-Keeper of the Left, Dead at 66". The Villager. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012.

- ^ "Joe Hill Papers". Walter P. Reuther Library. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ISBN 978-0870494895.

- ^ "Joe Hill (Alfred Hayes/Earl Robinson)(1936)". Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ISBN 1879407051.

- ISBN 9781604864830.

- ^ Ochs, Phil (January 19, 2002). "Joe Hill". Trent A. Fisher. Portland State University. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- Yahoo. Archived from the originalon July 28, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- IMDb

- ISBN 978-0-8222-0982-9. Archived from the originalon November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ "Raise Your Banners". Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "joe hill030.jpg". Gefle Dagblad (in Swedish). November 4, 2011. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "Dick Gaughan's Song Archive". Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Down The Road. Mickey Hart. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "Musical Theatre". SiKahn. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ Rudd, Roswell. Trombone For Lovers. Sunnyside Records. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

Recordings of songs

Cover albums of his songs:

- Joe Glazer, Songs of Joe Hill, Smithsonian Folkways, 1954

- Bucky Halker, Anywhere But Utah: Songs of Joe Hill, Revolting Records, 2015

Further reading

- Buhle, Paul; Schulman, Nicole, eds. (2005). Wobblies! A Graphic History of the Industrial Workers of the World. New York: Verso.

- Chaplin, Ralph (November 1923). "Joe Hill, a Biography". The Industrial Pioneer. Chicago: Industrial Workers of the World: 23–26.

- We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Quadrangle.

- Gibbs, Smith. Joe Hill: The Man and the Myth. Salt Lake: University of Utah Press.

- Leier, Mark (1989). Where the Fraser River Flows: The Industrial Workers of the World in British Columbia. New Star Books.

- Nolan, Dean; Thompson, Fred. Joe Hill: IWW Songwriter. Montreal: Kersplebedeb.

- Difranco, Ani(1999). Fellow Workers. NY: Righteous Babe Records.

- ISBN 0-88286-264-2.

- Stavis, Barrie (1954). The Man Who Never Died: A Play about Joe Hill, with Notes on Joe Hill and His Times. New York: Haven Press. — The "notes" are actually a carefully researched, 116-page history of the period, with detailed analysis of the trial of Joe Hill, including photographs of people, events, and documents. The play was produced in New York City off-broadway at the Jan Hus Play House in 1958.

- Stavis, Barrie (1972). The Man Who Never Died: A Play about Joe Hill, with Notes on Joe Hill and His Times. Cranbury NJ: A. S. Barnes. — revised play and compressed notes

- The Nightwatchman (2007). "Union Song". One Man Revolution.

External links

Video

- Joe Hill Documentary produced by PBS affiliate KUED.

- Discussion with William Adler, author of The Man Who Never Died: The Life, Times, and Legacy of Joe Hill, American Labor Icon on C-SPAN from October 29, 2011.

- Joe Hill documentary (Swedish with English subtitles)

Articles

YouTube Music

- Songs of Joe Hill, Joe Glazer, 1954, 10 songs, 22 minutes.

- Don't Mourn—Organize!: Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill, Various Artists, 1990, 15 songs, 54 minutes.

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

- Songs of Joe Hill. Can purchase a digital download of the recording, or alternatively a CD. (Music on the album also available on ad supported YouTube Music for free)

- Don't Mourn—Organize!: Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill. Can purchase a digital download of the recording released in 1990, or alternatively a CD. Can also download a PDF file of the liner notes for free. (Music on the album also available on ad supported YouTube Music for free)

Songs

- The Songs of Joe Hill at Folk Archive.

- Lyrics, sheet music, and audio files at Political Folk Music (About).

University of Utah Special Collections

- Joe Hill photograph collection, 1914–1990

- Joe Hill Organizing Committee records, 1914–1991

- Joe Hill Conference photograph collection, 1915–1990s

County Museum of Gävleborg, Sweden

Internet Archive

- Songs of the Workers to Fan the Flames of Discontent—IWW songbook

- Joe Hill melodies

- Swedish labor songs

- Songs of the Wobblies LP

- "Joe Hill": song by Alfred Hayes and Earl Robinson

- Works by Joe Hill at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)