Mao Kun map

Mao Kun map, usually referred to in modern Chinese sources as Zheng He's Navigation Map (

Origin

The map is thought by sinologist

The introduction to the map in Wubei Zhi indicates that the geographical and navigational details of the charts are based on works from the

According to Mills, the map may not have been the work of a single person, rather it was produced in an office with information added and corrected when new information became available after each voyage. He suggested that this map may have been prepared for the 6th expedition in 1421, with some content added during the course of the expedition, and that the map may, therefore, be dated to around 1422.[10] Others proposed a date sometime between 1423 and 1430.[8] It has also been suggested by J.J.L. Duyvendak and Paul Pelliot that the map may have been partly based on Arab nautical charts.[10]

Format and content

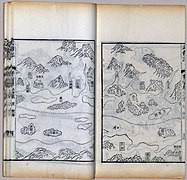

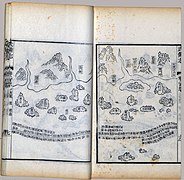

The map was originally in the form of a

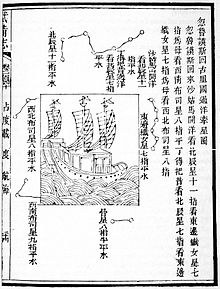

Also marked on the map as dotted lines are sailing routes, with instructions given along the route markings. The sailing instructions are given in compass points and distances – the compass point uses a

The map does not attempt to give a true or consistent representation in its scale or orientation – the scale can vary from 7 miles/inch in the Nanjing area to 215 miles/inch along parts of the African coast, and in some parts, such as the page with

Places on map

There are 499 place names in the map, 423 of these have been identified by Mills,[13] although some locations are identified differently by other authors.[17] Some misprints have been noted, for example Barawa or Brava is given as shi-la-wa (十剌哇), with shi (十) substituting for bu (卜). There are also unexplained omissions of centers known to be active in the period, such as Nakhon Si Thammarat of Thailand. Some of the places may also have been located in the wrong position. Despite its imperfections, it is considered a map of some significance that provides valuable information to historians.[2]

China

Almost half of the map (18 out of 40 pages) depicts the sailing route from

South East Asia

The map shows South East Asia in some details. Its main focus is on the route to the Western Ocean (西洋), a Chinese designation for the stretch of water starting from around Java or Sumatra to the

Among the places marked on the map are

South and West Asia

Some of the places marked include

. Sri Lanka appears significantly larger than it actually is in relation to India.Africa

The east coast of Africa is shown in sections of the map with Sri Lanka and India with its land mass at the top of the map and the Maldives in the middle. Places such as Mombasa (慢八撒), Barawa (卜剌哇), and Mogadishu (木骨都束) are marked on the map. Other locations identified include Lamu Island, Manda Island, and Jubba and Marka in Somalia.[14] What appears to be Malindi (麻林地) is shown in the wrong location to the right of Mombasa, and it has been suggested that this Malindi was meant to represent Mozambique or Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania.[13][19] Another proposal is that this portion of the map represents only the Kenya Coast and that Malindi was the terminus of the journey. In this scenario the place thought to be Mombasa would actually be Faza or Mfasa on Pate Island, and that the order of the places on the map would be correct. This proposal also suggests that the Zheng He voyages never traveled more than six degrees south of the Equator, which would explain the omission of the important trading center of Kilwa in Southern Tanzania.[14]

Gallery

- Mao Kun map

Arrangement in traditional Chinese format, to be read from right to left; first pages on top right, last pages on bottom left.

- Stellar charts

Popular culture

- The Sao Feng, and referred to as a Chinese allegory map, the navigational charts, the Map of the Land of the Dead or simply Sao Feng's Map in various media, while serving as the route to the Farthest Gate in the film. In an accompanying book for the following film, On Stranger Tides, the map was given the name Mao Kun Map though it was never said onscreen.[20]

See also

- History of Chinese cartography

- Cartography of China

- Chinese exploration

- Chinese geography

Similar maps

- Da Ming Hun Yi Tu, c. late 14th century

- Gangnido Map, 1402

- Sihai Huayi Zongtu, 1532

- Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, 1602

- Shanhai Yudi Quantu, 1609

- Selden Map, c. 17th century

Notes

- ^ Original text: 當是時,臣為內豎鄭和,亦不辱命. 焉,其圖列道里國土,詳而不誣,載以昭來世,志武功也。

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1402045592.

- ^ ISBN 978-0521010320.

- ^ Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1933). Ma Huan Re-examined. N. V. Noord-Hollandsche Uitgeversmaatschappij.

- ISBN 978-0521010320.

- OCLC 504030596.

- ISBN 978-1107018686.

- ISBN 978-9971695743.

- ^ ISBN 978-7-5027-6377-0.

- ISBN 9787501003044.

- ^ ISBN 978-0521010320.

- ISBN 978-1107018686.

- OCLC 504030596.

- ^ ISBN 978-0521010320.

- ^ ISBN 978-967-11386-0-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-9041110565.

- ^ a b Ulises Granados (2006). "The South China Sea and Its Coral Reefs during the Ming and Qing Dynasties: Levels of Geographical Knowledge and Political Control" (PDF). East Asian History. 32/33: 109–128.

- OCLC 504030596. Note for example the identification of the islands of Singapore

- ISBN 978-9004117730.

- JSTOR 1151020.

- ISBN 978-1405363419.

Further reading

- "Appendix 2-6". Ma Huan: Ying-yai sheng-lan 'The overall survey of the ocean's shores' (1433). Translated by J. V. G. Mills (New ed.). White Lotus Co. Ltd. 1996. ISBN 978-974-8496-78-8.

External links

- Wu Bei Zhi at the Library of Congress

- Mao Kun Explorer - An interactive application to explore the locations and shipping routes on the Mao Kun Map