Marquand Collection

The Art Collection of Henry Gurdon Marquand was a collection of antiques and paintings owned by Henry Gurdon Marquand, the second president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, until his death in 1902.

History

In the late 1840s, after the sale of his family's jewelry business and store (which was renamed to Ball, Tompkins & Black), Marquand traveled to Europe where he met Henry Kirke Brown and other expatriate American sculptors in Rome.[1] While there, he "began to 'frequent studios' and "to understand the artists' 'hopes, aims, and aspirations.' There Marquand fell under the spell of what Henry James called 'the old and complex civilization.'"[1] He returned in 1852 with his new wife and spent a year in Rome, where the first of their six children was born.[1] In 1889, he became the second president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[2] and made many significant gifts to the Metropolitan Museum,[3][4] including works by Filippo Lippi, Lucas van Leyden, Frans Hals, Anthony van Dyck, Rembrandt, Diego Velázquez, Thomas Gainsborough, John Trumbull and John Singer Sargent.[5][6]

Following his 1902 death, his collection exhibited at the American Art Galleries in New York before it was put up for auction.

"He bought like an Italian price of the Renaissance. He collected for his own delight and for the enjoyment and instruction of his many friends. A noble

Van Dyck portrait appealed to him, and so did a Persian vase. He was the most eager purchaser of a single newly found gem of antique art; he would chase the elusive thing with more energy than another, and therefore he secured the price. He felt also the impossibility of understanding a branch of art, or a special manufacture, or mode of design, without having many pieces to represent and explain it, and so he bought largely along some chosen lines."[10]

The sale of his collection brought $197,070 for 93 paintings (including A Reading from Homer by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema which sold for $30,300[a]),[12] $22,637 for "255 vases, jars, dishes, bowls, beakers, incense burners, water-vases, wine cups, and writer's water jars",[13] and $234,564 for rugs and tapestries, including a 15th or early 16th-century Persian rug that brought $38,000. Another $117,000 was received for enamels, pottery, bronzes, tiles and intaglios. A single retable (altar piece) brought $26,000.[9][b]

Collection

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

Paintings

-

Portrait of a Man and a Woman by Filippo Lippi (c. 1440)

-

The Lamentation by Petrus Christus (c. 1450)

-

Girl with Cherries, attributed toMarco da Oggiono(c. 1491–95)

-

Virgin and Child in a Niche (c. 1500)

-

Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of Pharaoh (c. 1534–47)

-

Twenty-one Plaques Depicting Prophets, Apostles and Sibyls byLéonard Limousin(between c. 1535 and c. 1540)

-

Portrait of a Man, Possibly Jean de Langeac, Bishop of Limoges (1539)

-

Portrait of a Man in a Fur-Trimmed Coat (c. 1540)

-

Susanna and the Elders by Peter Paul Rubens (between 1597 and 1640)

-

Portrait of a Woman by Cornelis de Vos (between 1599 and 1651)

-

Christ Presented to the People by Lucas van Leyden (16th century)

-

Portrait of a Man by Anthony van Dyck (c. 1618)

-

The Smoker, or Three Heads by Frans Hals (c. 1623–25)

-

Landscape with a Cottage by Pieter de Molijn (1629)

-

James Stuart, Duke of Richmond and Lennox by Anthony van Dyck (c. 1633–35)

-

Saint Michael the Archangel by Ignacio de Ries (1640s)

-

A Kitchen by Hendrik Martenszoon Sorgh (c. 1643)

-

Man with a Beard by Rembrandt (17th century)

-

Portrait of a Man by Diego Velázquez (c. 1650)

-

Portrait of a Woman by Frans Hals (c. 1650)

-

Portrait of a Man by Frans Hals (early 1650s)

-

The Good Samaritan by David Teniers the Younger (between 1651 and 1656)

-

Portrait of a Woman by Adriaen Hanneman (c. 1653)

-

Shepherds and Sheep by David Teniers the Younger (1650s)

-

Portrait of a Seated Man by Gerard ter Borch (late 1650s or early 1660s)

-

A Musical Party byGabriel Metsu(1659)

-

The Forest Stream by Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1660)

-

The Forest Stream by Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1660)

-

Woman with a Water Jug by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1662)

-

The Card Party by Caspar Netscher (c. 1665)

-

Girl Building a House of Cards by Thomas Frye (mid-18th century)

-

A Boy with a Cat—Morning by Thomas Gainsborough (1787)

-

Mariana of Austria, Queen of Spain by Diego Velázquez (17th century)

-

Man with a Beard by School of Rembrandt (17th century)

-

Landscape with Cattle by Jacob van Strij (c. 1800)

-

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull (1804–6)

-

Hautbois Common, Norfolk by John Crome (c. 1810)

-

Saltash with the Water Ferry, Cornwall by J. M. W. Turner (1811)

-

An Old Chapel in a Valley by Théodore Rousseau (c. 1835)

-

Amo Te, Ama Me by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1881)

-

A Reading from Homer Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1885)

-

Study for the Ceiling of the Marquand Music Room by Frederic Leighton (c. 1886)

-

Mnemosyne, Mother of the Muses by Frederic Leighton (c. 1886)

-

Portrait of Mabel Marquand Ward, by John Singer Sargent (c. 1891–94)

-

Portrait of Elizabeth Allen Marquand by John Singer Sargent (1887)

-

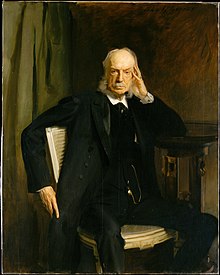

Portrait of Henry G. Marquand by John White Alexander (1896)

Furniture and stained glass

-

Wood and ivory cabinet (late 17th–early 18th century)

-

Table by Elkington & Co. (19th century, after 18th century original)

-

Bed from the Henry G. Marquand House in New York City (c. 1881–84)

-

Writing table from the Marquand House by Louis Comfort Tiffany (c. 1885)

-

Stained glass window from the conservatory of the Marquand House, designed by Hunt and made by Eugène Stanislas Oudinot (1883-1884)

-

1884Steinway grand piano designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema with painted panel by Sir Edward Poynter[c]

Sculptures

-

Bronze statuette of a youth (late 5th century B.C.)

-

Bronze statue of a camillus (acolyte) (ca. A.D. 14–54)

-

Statuette of a woman

-

Statuette of Aphrodite with apple

-

Bronze statuette of Cybele on a cart drawn by lions (2nd half of 2nd century A.D.)

-

Virgin and Child in a niche by Luca della Robbia (c. 1460)

-

Head-shaped flacon Glasshouse of Bernard Perrot, Verrerie Royale d'Orléans (c. 1700)

Decorative arts

-

Glass alabastron (perfume bottle) (late 6th–5th century B.C.)

-

Ewer, Delft (c. 1710–60)

-

Snuffbox (mid-18th century)

-

Nécessaire (c. 1760–80)

-

Chocolate pot with cover, Delft (1761–69)

-

Goblet and saucer Imperial Porcelain Manufactory (1804)

Illustrated Catalogue (1903)

-

Portrait of Peg Woffington by Tintoretto

-

Painting of Dedham Vale by John Constable (1811)

-

Landscape and cattle by Constant Troyon

-

Panel of painted and leaded glass (1570)

-

Panel of painted and leaded glass (1680)

-

Study for the Ceiling of the Marquand Music Room by Frederic Leighton (c. 1886)

-

Sculpture by François Duquesnoy

-

Rare cloth of gold tapestry

-

Screen orLéonard Limousin(1543)

-

Portrait of Marquand, by John Singer Sargent, 1897.

-

Amo Te, Ama Me by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1881)

-

Rich Venetian Velvet Panel (16th century)

-

Portrait of Mrs Wells by Sir Joshua Reynolds[d]

-

Portrait of young Shelley by John Hoppner (1805)

-

An Old Chapel in a Valley by Théodore Rousseau (c. 1835)

-

A Reading from Homer Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1885)

-

Antique Ivory Cabinet

-

1884Steinway grand piano designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

-

Greek and Roman Marble Sculpture

-

The Shy Child by George Romney (1790)

-

Hon. Mrs. Stanhope, print made by John Raphael Smith after Sir Joshua Reynolds

-

Gobelins tapestry (Louis XV period) (1735)

-

Wood and ivory corner cabinet

-

Large old English Hall armchair (one of two) and Old English high-backed char (one of four)

-

Mariana: Measure for Measure" by Edwin Austin Abbey

-

Madonna and child Luca della Robbia (15th century)

References

- Notes

- Pentimenti show that the composition continued to evolve: for example, Alma-Tadema changed the speaker's arm, which had been thrown out in a dramatic declamatory gesture.[11]

- ^ The painted enamel plaques in gilt screen by Léonard Limosin were purchased by Marquand in April 1883 during the Beurdeley sale. During the 1903 Marquand sale, it was purchased by Henry Walters for $26,000. Upon Walters' death, he bequeathed the piece to the Walters Art Museum in 1931.[14]

- West 45th Street. In 1980, after fifty years in the upstairs lounge, the piano was sold at auction for $390,000 which, at the time, was "the highest price ever paid for a musical instrument or for any piece of 19th century furniture."[16]

- ^ Marquand acquired the painting from the collection of The Rt. Hon. Edward Pleydell-Bouverie. In the 1903 sale, the painting was incorrectly listed as by George Romney and was acquired by Sir [R?] Cooper. In 2008, it was sold by Christie's for £49,250.[17]

- Sources

- ^ ISBN 978-0-670-01831-4. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "HENRY G. MARQUAND DEAD; His Career as a Business Man and a Patron of Art--Funeral to Take Place To-morrow. President of the Metropolitan Museum Passes Away at His Home". The New York Times. 27 February 1902. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "MR. MARQUAND'S GREAT GIFT.; HIS VALUABLE PAINTINGS TO GO TO THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM". The New York Times. 16 January 1889. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "THE MARQUAND PICTURES". The New York Times. 28 January 1889. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ProQuest 94683872.

- ^ "THE MARQUAND DONATION". The New York Times. 20 January 1889. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- The Churchman. Churchman Company. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "THE MARQUAND COLLECTION.; The Rugs, Tapestries, Furniture, Antique Glass, Tiles, and Terra Cottas". The New York Times. 22 January 1903. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b "THE MARQUAND SALE". The New York Times. 2 February 1903. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b Marquand, Henry Gurdon; Kirby, Thomas E. (1903). Illustrated Catalogue of the Art and Literary Property Collected by the late Henry G. Marquand. Press of J. J. Little & Co. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ British Painting in the Philadelphia Museum of Art: From the Seventeenth through the Nineteenth Century, 1986, p.3-8

- ^ "MARQUAND PICTURE SALE; Total on the First Day for Ninety-three Paintings, $197,070. " A Reading from Homer," by Alma-Tadema, Brought $30,300, and a Portrait of Mrs. Gwyn $22,200". The New York Times. 24 January 1903. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "PORCELAINS AT AUCTION; Marquand Treasures Bring $22,637.50 on Second Day's Sale". The New York Times. 25 January 1903. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- The Walters Art Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "WHAT COST THE MOST.; A FEW ARTICLES FOR WHICH THE HIGHEST PRICES HAVE BEEN PAID". The New York Times. 21 May 1888. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b Reif, Rita (27 March 1980). "Piano Sold At $390,000, A Record". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A. (Plympton Devon 1723-1792 London)". www.christies.com. Christie's. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

Portrait of Mrs Wells, three-quarter-length, seated, in a striped dress and straw hat

External links

- Collecting Old Masters for New York, Esmée Quodbach

![1884 Steinway grand piano designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema with painted panel by Sir Edward Poynter[c]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/Clark_Art_Institute_-_piano_a.JPG/120px-Clark_Art_Institute_-_piano_a.JPG)

![Portrait of Mrs Wells by Sir Joshua Reynolds[d]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Illustrated_catalogue_of_the_art_and_literary_property_collected_by_the_late_Henry_G._Marquand_%281903%29_%2814758543706%29.jpg/96px-Illustrated_catalogue_of_the_art_and_literary_property_collected_by_the_late_Henry_G._Marquand_%281903%29_%2814758543706%29.jpg)