Posy Simmonds

| Posy Simmonds | |

|---|---|

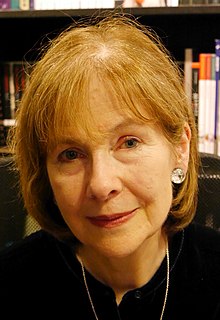

Simmonds at Hatchards, London, November 2018 | |

| Born | Rosemary Elizabeth Simmonds 9 August 1945 Berkshire, England |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist Illustrator Writer |

Notable works | Gemma Bovery Tamara Drewe |

| Awards | MBE, Prix de la critique, British Comic Awards Hall of Fame (2014) |

Rosemary Elizabeth "Posy" Simmonds

Early life

Posy Simmonds was born in

Career

Simmonds started her newspaper career drawing a daily cartoon, "Bear", for The Sun in 1969. She contributed humorous illustrations to The Times from 1968 to 1970. She also contributed to Cosmopolitan, and a satirical cartoon to Tariq Ali's Black Dwarf magazine. She moved to The Guardian as an illustrator in 1972.

In May 1977 she started drawing a weekly comic strip for The Guardian, initially titled The Silent Three of St Botolph's as a tribute to the 1950s strip The Silent Three by Evelyn Flinders. It began as a silly parody of girls' adventure stories making satirical comments about contemporary life. The strip soon focused on three 1950s schoolfriends in their later, middle-class and nearly middle-aged lives: Wendy Weber, a former nurse married to polytechnic sociology lecturer George with a large brood of children; Jo Heep, married to whisky salesman Edmund with two rebellious teenagers; and Trish Wright, married to philandering advertising executive Stanhope and with a young baby. The strip, which was latterly untitled and usually known just as "Posy", ran until the late 1980s. It was collected into a number of books: Mrs Weber's Diary, Pick of Posy, Very Posy and Pure Posy, and one original book featuring the same characters, True Love. Her later cartoons for The Guardian and The Spectator were collected as Mustn't Grumble in 1993.

In 1981, Simmonds was named Cartoonist of the Year

In the late 1990s Simmonds returned to the pages of The Guardian with Gemma Bovery, which reworked the story of Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary into a satirical tale of English expatriates in France. It was published as a graphic novel in 1999 and was made into a feature film of the same name (Gemma Bovery), directed by Anne Fontaine, in 2014, and starring Gemma Arterton.[6] The Literary Life series of cartoons appeared in The Guardian's "Review" section on Saturdays from November 2002 until December 2004, and was published in book form in 2003 (Literary Life) and, in an expanded version, in 2017 (Literary Life Revisited).

Simmond's 2005-6 Guardian series, Tamara Drewe, which echoes Thomas Hardy's novel Far From the Madding Crowd, made its début in the Review section on 17 September 2005, in the first Saturday paper after the Guardian's relaunch in the Berliner format. It ended, with episode 109 and an epilogue, on 2 December 2006 and was published as a book in 2007. In 2010 the story was adapted as a feature film of the same name, directed by Stephen Frears from a screenplay by Moira Buffini, again starring Gemma Arterton.[7]

Simmonds' third, critically acclaimed graphic novel, Cassandra Darke, was published in 2018.[8][9][10] It is loosely based on Charles Dickens' novella A Christmas Carol; although the story unfolds in 2016-17, its eponymous protagonist is in some respects a female version of Ebenezer Scrooge, and also undergoes a profound (though more subtle and ambiguous) moral transformation.

Simmonds drew the illustrations for the opening titles of the

Selected bibliography

- The Posy Simmonds Bear Book (1969)

- Bear (1974)

- More Bear (1975)

- Mrs Weber's Diary (1979)

- True Love (1981)

- Pick of Posy (1982)

- Very Posy (1985)

- Pure Posy (1987)

- Mustn't Grumble (1993)

- Gemma Bovery (1999)

- Literary Life (2003)

- Tamara Drewe (2007)[16]

- Cassandra Darke (2018)

Children's books

- Fred (1987)

- Lulu and the Flying Babies (1988)

- The Chocolate Wedding (1990)

- Matilda: Who Told Lies and Was Burned To Death (1991)

- Bouncing Buffalo (1994)

- F-Freezing ABC (1996)

- Cautionary Tales And Other Verses (1997)

- Mr Frost (2001, in Little Litt #2)

- Lavender (2003)

- Baker Cat (2004)

Television/film scripts

- The Frog Prince (1984)

- Tresoddit for Easter (1991)

- Famous Fred (1996)

References

- ^ "Paul Gravett interviewing Posy Simmonds". 4 November 2007.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-954088-4. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "BBC News, June 2002". BBC News. 14 June 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ "Simmonds's satirical touch". BBC News. 14 June 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ "Press Awards Winners 1980 - 1989". Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ The Falmouth School of Art (2 March 2015). "Posy Simmonds lecture". Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Interview: Posy Simmonds, cartoonist", The Scotsman, 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Cassandra Darke by Posy Simmonds review – a Christmas Carol for our time". the Guardian. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Cassandra Darke by Posy Simmonds — snob appeal". Financial Times. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Simmonds's satirical touch", BBC News, 14 June 2002.

- ^ "Lauréat 2009" (in French). ACBD. December 2008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ^ "Bande dessinée – Posy Simmonds recevra le Grand Prix Töpffer".

- ^ "Les prix Rodolphe Töpffer - Département de la culture et de la transition numérique - Ville de Genève".

- ^ "Posy Simmonds wins Grand Prix at Angoulême Comics Festival". Le Monde.fr. 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "Briefly Noted," The New Yorker (3 November 2008).

External links

- Tamara Drewe archive

- Literary Life archive

- Lambiek comiclopedia entry on Posy Simmonds

- Profile from the British Council's "Magic Pencil" exhibition

- Posy Simmonds talks drawing, writing and Tamara Drewe with ITV Local Anglia

- Clive James interview with Posy Simmonds

- BBC Radio 4, Desert Island Discs, first broadcast on 29 June 2008

- Paul Gravett interview

- MsLexia profile/interview

- Telegraph profile/interview

- Guardian profile/interview

- "Tamara Drewe's Wessex: an article in the TLS by Mick Imlah, 14 November 2007