Potato

| Potato | |

|---|---|

| |

| Potato cultivars appear in a variety of colors, shapes, and sizes. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Solanum |

| Species: | S. tuberosum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Solanum tuberosum | |

| Synonyms | |

|

see list | |

The potato (

Wild potato

The Spanish

Like the tomato and the nightshades, the potato is in the genus

Etymology

The English word "potato" comes from Spanish patata, in turn from Taíno batata, which means "sweet potato", not the plant now known as simply "potato".[1]

The name "spud" for a potato is from the 15th century spudde, a short knife or dagger, probably related to Danish spyd, "spear". From around 1840, the name transferred to the tuber itself.[2]

At least six languages—Afrikaans, Dutch, French, (West) Frisian, Hebrew, Persian[3] and some variants of German—use a term for "potato" that means "earth apple" or "ground apple".[4][5]

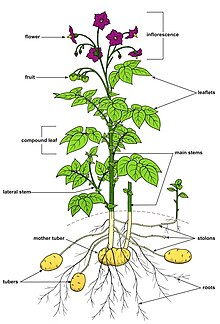

Description

Potato plants are herbaceous perennials that grow up to 1 metre (3.3 ft) high. The stems are hairy. The leaves have roughly four pairs of leaflets. The flowers range from white or pink to blue or purple; they are yellow at the centre, and are insect-pollinated.[6]

The plant develops

After flowering, potato plants produce small green fruits that resemble green cherry tomatoes, each containing about 300 very small seeds.[9]

Phylogeny

Wild and cultivated potatoes, like the tomato, belong to the genus Solanum, which is a member of the nightshade family, the Solanaceae. That is a diverse family of flowering plants, often poisonous, that includes the mandrake (Mandragora), deadly nightshade (Atropa), and tobacco (Nicotiana), as shown in the outline phylogenetic tree (many branches omitted). The most commonly cultivated potato is S. tuberosum; there are several other species.[10]

| Solanaceae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The major species grown worldwide is S. tuberosum (a

There are two major subspecies of S. tuberosum.[11] The Andean potato, S. tuberosum andigena, is adapted to the short-day conditions prevalent in the mountainous equatorial and tropical regions where it originated. The Chilean potato S. tuberosum tuberosum, native to the Chiloé Archipelago, is in contrast adapted to the long-day conditions prevalent in the higher latitude region of southern Chile.[12]

History

Domestication

Wild potato species occur from the southern United States to southern Chile.[13] The potato was first domesticated in southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia[14] by pre-Columbian farmers, around Lake Titicaca.[15] Potatoes were domesticated there about 7,000–10,000 years ago from a species in the S. brevicaule complex.[14][15][16]

The earliest archaeologically verified potato tuber remains have been found at the coastal site of Ancon (central Peru), dating to 2500 BC.[17][18] The most widely cultivated variety, Solanum tuberosum tuberosum, is indigenous to the Chiloé Archipelago, and has been cultivated by the local indigenous people since before the Spanish conquest.[12][19]

Spread

Following the

The International Potato Center, based in Lima, Peru, holds 4,870 types of potato germplasm, most of which are traditional landrace cultivars.[23] In 2009 a draft sequence of the potato genome was made, containing 12 chromosomes and 860 million base pairs, making it a medium-sized plant genome.[24]

It had been thought that most potato

Most modern potatoes grown in North America arrived through European settlement and not independently from the South American sources. At least one wild potato species,

Little of the diversity found in Solanum ancestral and wild relatives is found outside the original South American range.[28] This makes these South American species highly valuable in breeding.[28] The importance of the potato to humanity is recognised in the United Nations International Day of Potato, to be celebrated on 30 May each year, starting in 2024.[29]

Breeding

Potatoes, both S. tuberosum and most of its wild relatives, are

Varieties

There are some 5,000 potato varieties worldwide, 3,000 of them in the Andes alone — mainly in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia. Over 100 cultivars might be found in a single valley, and a dozen or more might be maintained by a single agricultural household.[35][36] The

For culinary purposes, varieties are often differentiated by their waxiness: floury or mealy baking potatoes have more starch (20–22%) than waxy boiling potatoes (16–18%). The distinction may also arise from variation in the comparative ratio of two different potato starch compounds: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose, a long-chain molecule, diffuses from the starch granule when cooked in water, and lends itself to dishes where the potato is mashed. Varieties that contain a slightly higher amylopectin content, which is a highly branched molecule, help the potato retain its shape after being boiled in water.[39] Potatoes that are good for making potato chips or potato crisps are sometimes called "chipping potatoes", which means they meet the basic requirements of similar varietal characteristics, being firm, fairly clean, and fairly well-shaped.[40]

Immature potatoes may be sold fresh from the field as "creamer" or "new" potatoes and are particularly valued for their taste. They are typically small in size and tender, with a loose skin, and flesh containing a lower level of starch than other potatoes. In the United States they are generally either a Yukon Gold potato or a red potato, called gold creamers or red creamers respectively.[41][42] In the UK, the Jersey Royal is a famous type of new potato.[43]

Dozens of potato

Genetic engineering

Genetic research has produced several

Potato starch contains two types of glucan, amylose and amylopectin, the latter of which is most industrially useful. Waxy potato varieties produce waxy potato starch, which is almost entirely amylopectin, with little or no amylose. BASF developed the 'Amflora' potato, which was modified to express antisense RNA to inactivate the gene for granule bound starch synthase, an enzyme which catalyzes the formation of amylose.[49] 'Amflora' potatoes therefore produce starch consisting almost entirely of amylopectin, and are thus more useful for the starch industry. In 2010, the European Commission cleared the way for 'Amflora' to be grown in the European Union for industrial purposes only—not for food. Nevertheless, under EU rules, individual countries have the right to decide whether they will allow this potato to be grown on their territory. Commercial planting of 'Amflora' was expected in the Czech Republic and Germany in the spring of 2010, and Sweden and the Netherlands in subsequent years.[50]

The 'Fortuna' GM potato variety developed by BASF was made resistant to

In October 2011 BASF requested cultivation and marketing approval as a feed and food from the EFSA. In 2012, GMO development in Europe was stopped by BASF.[54][55] In November 2014, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved a genetically modified potato developed by Simplot, which contains genetic modifications that prevent bruising and produce less acrylamide when fried than conventional potatoes; the modifications do not cause new proteins to be made, but rather prevent proteins from being made via RNA interference.[56]

Genetically modified varieties have met public resistance in the U.S. and in the European Union.[57][58]

Cultivation

Seed potatoes

Potatoes are generally grown from "seed potatoes", tubers specifically grown to be free from disease[clarification needed] and to provide consistent and healthy plants. To be disease free, the areas where seed potatoes are grown are selected with care. In the US, this restricts production of seed potatoes to only 15 states out of all 50 states where potatoes are grown.[59] These locations are selected for their cold, hard winters that kill pests and summers with long sunshine hours for optimum growth.[citation needed] In the UK, most seed potatoes originate in Scotland, in areas where westerly winds reduce aphid attacks and the spread of potato virus pathogens.[60][failed verification]

Phases of growth

Potato growth can be divided into five phases. During the first phase, sprouts emerge from the seed potatoes and root growth begins. During the second,

New tubers may start growing at the surface of the soil. Since exposure to light leads to an undesirable greening of the skins and the development of solanine as a protection from the sun's rays, growers cover surface tubers. Commercial growers cover them by piling additional soil around the base of the plant as it grows (called "hilling" up, or in British English "earthing up"). An alternative method, used by home gardeners and smaller-scale growers, involves covering the growing area with mulches such as straw or plastic sheets.[63]

At farm scale, potatoes require a well-drained neutral or mildly acidic soil (

-

Planting

-

Field in Fort Fairfield, Maine

-

Immature potato plants

-

Potatoes grown in a tall bag are common in gardens as they minimize digging.

Pests and diseases

The historically significant

Insects that commonly transmit potato diseases or damage the plants include the

Harvest

On a small scale, potatoes can be harvested using a hoe or spade, or simply by hand. Commercial harvesting is done with large potato harvesters, which scoop up the plant and surrounding earth. This is transported up an apron chain consisting of steel links several feet wide, which separates some of the earth. The chain deposits into an area where further separation occurs. The most complex designs use vine choppers and shakers, along with a blower system to separate the potatoes from the plant. The result is then usually run past workers who continue to sort out plant material, stones, and rotten potatoes before the potatoes are continuously delivered to a wagon or truck. Further inspection and separation occurs when the potatoes are unloaded from the field vehicles and put into storage.[72]

Potatoes are usually cured after harvest to improve skin-set. Skin-set is the process by which the skin of the potato becomes resistant to skinning damage. Potato tubers may be susceptible to skinning at harvest and suffer skinning damage during harvest and handling operations. Curing allows the skin to fully set and any wounds to heal. Wound-healing prevents infection and water-loss from the tubers during storage. Curing is normally done at relatively warm temperatures (10 to 16 °C or 50 to 60 °F) with high humidity and good gas-exchange if at all possible.[73]

Storage

Storage facilities need to be carefully designed to keep the potatoes alive and slow the natural process of sprouting which involves the breakdown of starch. It is crucial that the storage area be dark, ventilated well, and, for long-term storage, maintained at temperatures near 4 °C (39 °F). For short-term storage, temperatures of about 7 to 10 °C (45 to 50 °F) are preferred.[74]

Temperatures below 4 °C (39 °F) convert the starch in potatoes into sugar, which alters their taste and cooking qualities and leads to higher acrylamide levels in the cooked product, especially in deep-fried dishes. The discovery of acrylamides in starchy foods in 2002 has caused concern, but it is not likely that the acrylamides in food, even if it is somewhat burnt, causes cancer in humans.[75]

Chemicals are used to suppress sprouting of tubers during storage.

Under optimum conditions in commercial warehouses, potatoes can be stored for up to 10–12 months.

Production

| Potato production – 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

| 94.3 | |

| 54.2 | |

| 21.4 | |

| 18.6 | |

| 18.3 | |

| World | 376 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[77]

| |

-

Production of potatoes (2019)[78]

-

Potatoes are one of the most widely produced primary crops in the world.

In 2021, world production of potatoes was 376 million tonnes (370,000,000 long tons; 414,000,000 short tons), led by China with 25% of the total. Other major producers were India and Ukraine (table).

The world dedicated 18.6 million hectares (46 million acres) to potato cultivation in 2010; the world average yield was 17.4 tonnes per hectare (7.8 short tons per acre). The United States was the most productive country, with a nationwide average yield of 44.3 tonnes per hectare (19.8 short tons per acre).[79]

New Zealand farmers have demonstrated some of the best commercial yields in the world, ranging between 60 and 80 tonnes per hectare, some reporting yields of 88 tonnes of potatoes per hectare.[80][81][82]

There is a big gap among various countries between high and low yields, even with the same variety of potato. Average potato yields in developed economies ranges between 38 and 44 metric tons per hectare (15 and 18 long ton/acre; 17 and 20 short ton/acre). China and India accounted for over a third of world's production in 2010, and had yields of 14.7 and 19.9 metric tons per hectare (5.9 and 7.9 long ton/acre; 6.6 and 8.9 short ton/acre) respectively.

Impact of climate change on production

Potato plants and crop yields are predicted to benefit from the

Potatoes grow best under temperate conditions.[93] Temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) have negative effects on potato crops, from physiological damage such as brown spots on tubers, to slower growth, premature sprouting, and lower starch content.[94] These effects reduce crop yield, affecting both the number and the weight of tubers. As a result, areas where current temperatures are near the limits of potatoes' temperature range (e.g. much of sub-Saharan Africa)[86] will likely suffer large reductions in potato crop yields in the future.[93] On the other hand, low temperatures reduce potato growth and present risk of frost damage.[86]

Changes in pests and diseases

Climate change is predicted to affect many potato pests and diseases. These include:

- Insect pests such as the potato tuber moth and Colorado potato beetle, which are predicted to spread into areas currently too cold for them.[86]

- Aphids which act as vectors for many potato viruses and will spread under increased temperatures.[95]

- Pathogens causing potato blackleg disease (e.g. Dickeya) grow and reproduce faster at higher temperatures.[96]

- Bacterial infections such as Ralstonia solanacearum will benefit from higher temperatures and spread more easily through flash flooding.[86]

Adaptation strategies

Potato production is expected to decline in many areas due to hotter temperatures and decreased water availability. Conversely, production is predicted to become possible in high altitude and latitude areas where it has been limited by frost damage, such as in Canada and Russia.[93] This will shift potato production to cooler areas, mitigating much of the projected decline in yield. However, this may trigger competition for land between potato crops and other land uses, mostly due to changes in water and temperature regimes.[93]

The other approach is through the development of varieties or cultivars which would be more adapted to altered conditions. This can be done through 'traditional'

For instance, developing cultivars with greater heat stress tolerance would be critical for maintaining yields in countries with potato production areas near current cultivars' maximum temperature limits (e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa, India).[98] Superior drought resistance can be achieved through improved water use efficiency (amount of food produced per amount of water used) or the ability to recover from short drought periods and still produce acceptable yields. Further, selecting for deeper root systems may reduce the need for irrigation.[99]

Content

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 364 kJ (87 kcal) |

20.1 g | |

| Sugars | 0.9 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.8 g |

0.1 g | |

1.9 g | |

Niacin (B3) | 9% 1.44 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 10% 0.52 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 18% 0.3 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 3% 10 μg |

| Vitamin C | 14% 13 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 0% 5 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.31 mg |

| Magnesium | 5% 22 mg |

| Manganese | 6% 0.14 mg |

| Phosphorus | 4% 44 mg |

| Potassium | 13% 379 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 4 mg |

| Zinc | 3% 0.3 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 77 g |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[100] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[101] | |

In a reference amount of 100 grams (3.5 oz), a boiled potato with skin supplies 87 calories and is 77% water, 20% carbohydrates (including 2% dietary fiber in the skin and flesh), 2% protein, and contains negligible fat (table). The protein content is comparable to other starchy vegetable staples, as well as grains.[102]

Boiled potatoes are a rich source (20% or more of the

The potato is rarely eaten raw because raw potato starch is poorly digested by humans.

In the UK, potatoes are not considered by the National Health Service as counting or contributing towards the recommended daily five portions of fruit and vegetables, the 5-A-Day program.[105]

Toxicity

Raw potatoes contain toxic glycoalkaloids, of which the most prevalent are solanine and chaconine. Solanine is found in other plants in the same family, Solanaceae, which includes such plants as deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna), henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) and tobacco (Nicotiana spp.), as well as food plants like tomato. These compounds, which protect the potato plant from its predators, are especially concentrated in the aerial parts of the plant. The tubers are low in these toxins, unless they are exposed to light, which makes them go green.[106][107]

Exposure to light, physical damage, and age increase glycoalkaloid content within the tuber.

Uses

Culinary

-

Pommes frites, also called chips and French fries

-

Baked potato with sour cream and chives

-

German Bauernfrühstück ("farmer's breakfast")

Other uses

Potatoes are sometimes used to brew alcoholic spirits such as vodka, poitín, akvavit, and brännvin.[119][120]

Potatoes are used as fodder for livestock. They may be made into silage which can be stored for some months before use.[121][122]

Potato starch is used in the food industry as a thickener and binder for soups and sauces, in the textile industry as an adhesive, and in the paper industry for the manufacturing of papers and boards.[123][124]

Potatoes are commonly used in plant research. The consistent parenchyma tissue, the clonal nature of the plant and the low metabolic activity make it an ideal model tissue for experiments on wound-response studies and electron transport.[125]

Cultural significance

In mythology

In Inca mythology, a daughter of the earth mother Pachamama, Axomamma, is the goddess of potatoes. She ensured the fertility of the soil and the growth of the tubers.[126] According to Iroquois mythology, the first potatoes grew out of Earth Woman's feet after she died giving birth to her twin sons, Sapling and Flint.[127]

In art

The potato has been an essential crop in the Andes since the

-

Potato ceramic from theMocheculture

-

The potato harvest by Jules Bastien-Lepage, 1877, National Gallery of Victoria

-

Van Gogh, 1885 (Van Gogh Museum)

-

Girl peeling potatoes by Albert Anker, 1886, oil on canvas

In popular culture

Invented in 1949, and marketed and sold commercially by Hasbro in 1952, Mr. Potato Head is an American toy that consists of a plastic potato and attachable plastic parts, such as ears and eyes, to make a face. It was the first toy ever advertised on television.[132][133][134]

In the 2015 fictionalized film, The Martian, stranded astronaut and botanist, Mark Watney, cultivates potatoes in the artificial crew habitat using Martian soil fertilized with frozen feces, and produces water from unused rocket fuel.[135]

See also

- Irish potato candy

- List of potato museums

- Loy (spade), a form of early spade used in Ireland for the cultivation of potatoes

- New World crops

- Potato battery

- International Year of the Potato

References

- ISBN 978-84-00-08266-6. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "spud (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "jordäpple | SAOB | svenska.se" (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Hooshmand, Dana (12 October 2020). ""Earth Apple": The 5 Languages that Use This for "Potato"". discoverdiscomfort.com. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Laws, Christopher (9 February 2015). "A Cultural History of the Potato as Earth Apple". Culturedarm. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Solanum tuberosum: Potato". Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-471-57339-5.

- International Journal of Developmental Biology (45): S37–S38. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ISBN 0-89118-034-6.

- ^ Olmstead, Richard G., et al. "Phylogeny and provisional classification of the Solanaceae based on chloroplast DNA." Solanaceae IV 1.1 (1999): 1-137. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tharindu-Ranasinghe-2/post/Is-there-a-complete-phylogenetic-description-of-the-Solanaceae-family/attachment/59d63db579197b807799a764/AS%3A421051545735172%401477397919618/download/PHYLOGENY+AND+PROVISIONAL+CLASSIFICATION+OF+THE+SOLANACEAE+BASED+ON+CHLOROPLAST+DNA.pdf

- ^ University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ hdl:10925/320. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- PMID 21669641.

- ^ PMID 16203994.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-309-04264-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85109-421-9.

- ^ Martins-Farias 1976; Moseley 1975

- ISBN 978-1-317-59829-9.

- ^ "Using DNA, scientists hunt for the roots of the modern potato". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ ISBN 9780367449872

- S2CID 17631317. Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ PMID 30731850.

- ^ "Cultivated Potato Genebank". International Potato Center. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- .

- S2CID 41052277.

- PMID 12872003.

- PMID 35576021.

- ^ S2CID 30648732.

- ^ "United Nations: International Day of Potato: 30 May". United Nations. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ PMID 34230471.

- S2CID 40678039.

- PMID 34230469.

- S2CID 39719359.

- S2CID 260349512.

- ^ Theisen, K (1 January 2007). "History and overview". World Potato Atlas: Peru. International Potato Center. Archived from the original on 14 January 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Solanum tuberosum L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Europotato.org". Europotato.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ Potato Council. "Potato Varieties". Agriculture & Horticulture Development Board. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- Cooks Illustrated. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Agricultural Marketing Service. "Potatoes for Chipping Grades and Standards". Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Creamer Potato". recipetips.com. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "What is a new potato? New guidelines issued". BBC News. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "A look back at a Royal history". 25 January 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "So many varieties, so many choices". Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association. 2017.

- PMID 23589519.

- S2CID 34297429.

- PMID 21520708.

- ^ "Genetically Engineered Organisms Public Issues Education Project/Am I eating GE potatoes?". Cornell University. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ "GMO compass database". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "GM potatoes: BASF at work". 31 May 2010. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010.

- ^ S2CID 247999992.

- ^ "Research in Germany: Business BASF applies for approval for another biotech potato". 2 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013.

- ^ Burger, Ludwig (10 November 2015). "BASF applies for EU approval for Fortuna GM potato | Reuters". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015.

- ^ BASF stops GM crop development in Europe, Deutsche Welle, 17 January 2012

- ^ Kanter, James (16 January 2012). "BASF to Stop Selling Genetically Modified Products in Europe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 January 2024. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (7 November 2014). "U.S.D.A. Approves Modified Potato. Next Up: French Fry Fans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Consumer acceptance of genetically modified potatoes" (PDF). American Journal of Potato Research. 2002. cited through Bnet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (24 July 2007). "A genetically modified potato, not for eating, is stirring some opposition in Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ United States Potato Board. "Seed Potatoes". Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Seed & Ware Potatoes". www.sasa.gov.uk. Scottish Agricultural Science Agency; Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ "Potatoes Home Garden". sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu. UF/IFAS Extension. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ISSN 0003-4746.

- Extension Service. Archived from the original(PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Potato Production USAID-Inma -- POTATO PRODUCTION: PLANTING THROUGH HARVEST" (PDF). USAID. pp. 2–21. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "How to grow potatoes: Planting". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "Potatoes". The National Allotment Society. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Organic Management of Late Blight of Potato and Tomato (Phytophthora infestans)". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ "Potato, Identifying Diseases". University of Massachusetts Amherst. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Potato Disease Identification". Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Alyokhin, A. (2009). "Colorado potato beetle management on potatoes: current challenges and future prospects" (PDF). In Tennant, P.; Benkeblia, N. (eds.). Potato II. Fruit, Vegetable and Cereal Science and Biotechnology 3 (Special Issue 1). pp. 10–19.

- ^ "Potato Cyst Nematode". Agriculture Victoria. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- PMID 37284722.

- ^ Kleinkopf, G.E.; Olsen, N. (2003). "Storage Management". In J.C. Stark; S.L. Love (eds.). Potato Production Systems. University of Idaho Agricultural Communications. pp. 363–381.

- ^ a b c Potato storage, value Preservation: Kohli, Pawanexh (2009). "Potato storage and value Preservation: The Basics" (PDF). CrossTree techno-visors. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ "Can eating burnt foods cause cancer?". Cancer Research UK. 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b Epp, Melanie (12 April 2021). "The Worry with CIPC". EuropeanSeed. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Potato production in 2021 Region/World/Production Quantity/Crops from pick lists". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division. 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- S2CID 240163091. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Sarah Sinton (2011). "There's yet more gold in them thar "hills"!". Grower Magazine, The Government of New Zealand.

- ^ "Phosphate and potatoes". Ballance. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "International Year of the Potato: 2008, Asia and Oceania". Potato World. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Workshop to Commemorate the International Year of the Potato. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2008.

- S2CID 4346486.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-8981-8.

- ^ S2CID 22794078.

- PMID 28811375.

- ^ "Potato". CIP. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ISSN 0032-0862.

- ^ a b "Climate change and potatoes: The risks, impacts and opportunities for UK potato production" (PDF). Cranfield Water Science Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Crop Water Information: Potato". FAO Water Development and Management Unit. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ISSN 0021-8596.

- ^ S2CID 3355406.

- ^ S2CID 602971.

- ^ Pandey, S.K. "Potato Research Priorities in Asia and the Pacific Region". FAO. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Czajkowski, R. "Why is Dickeya spp. (syn. Erwinia chrysanthemi) taking over? The ecology of a blackleg pathogen" (PDF). Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Forbes, G.A. "Implications for a warmer, wetter world on the late blight pathogen: How CIP efforts can reduce risk for low-input potato farmers" (PDF). CIP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Information highlights from World Potato Congress, Kunming, China, April 2004" (PDF). World Potato Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Potato and water resources". FAO. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- PMID 30844154.

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 15800557.

- ^ "5 A Day: what counts?". nhs.uk. 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Tomato-like Fruit on Potato Plants". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on 16 July 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ISSN 0735-2689.

- Food Science Australia. 2005. Archived from the originalon 25 November 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Koerth-Baker, Marggie (25 March 2013). "The case of the poison potato". boingboing.net. Archived from the original on 8 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- PMID 12720378.

- ISBN 978-3-540-21286-7.

- ^ Hayes, Monte (24 June 2007). "Peru Celebrates Potato Diversity". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ISBN 0-8165-1023-7, pp. 82–84

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Early Potato gets protected European status". BBC News. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-89480-845-6.

- ^ "D.E.L.A.C." delac.eu. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-09-976220-1.

- ISBN 978-0-85561-688-5.

- ISBN 1-59033-594-5.

- ^ Brännvinsbränning Archived 21 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine in Nordisk familjebok, volume 4 (1905)

- ^ Halliday, Les; et al. (2015). "Ensiling Potatoes" (PDF). Prince Edward Island Agriculture and Fisheries. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Schroeder, Ken (October 2012). "Feeding Cull Potatoes to Dairy and Beef Cattle" (PDF). University of Wisconsin Extension. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-306-45583-4.

- ISBN 978-1-56022-272-9.

- ISSN 0030-7270.

- OCLC 1242739583.

- ^ Converse, Harriet Maxwell (Ya-ie-wa-no); Parker, Arthur Caswell (Ga-wa-so-wa-neh) (15 December 1908). "Myths and Legends of the New York State Iroquois". Education Department Bulletin. University of the State of New York: 31–41 "Creation: Ata-en-sic, the Sky Woman" and "The Sun, Moon and Stars". Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York:Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-5628-4.

- ^ van Tilborgh, Louis (2009). "The Potato Eaters by Vincent van Gogh". The Vincent van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ISBN 1857592433

- ^ "Mr Potato Head". Museum of Childhood. V&A Museum of Childhood. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "About Mr. Potato Head". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ISBN 0-7407-5571-4.

- ^ "Could we grow potatoes on Mars?". Knowledge Centre, University of Warwick. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

Further reading

- Atlas of Wild Potatoes (2002), Systematic and Ecogeographic Studies on Crop Genepools 10, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), ISBN 9789290435181

- Economist. "Llamas and mash", The Economist 28 February 2008

- Economist. "The potato: Spud we like", (leader) The Economist 28 February 2008

- Bohl, William H.; Johnson, Steven B., eds. (2010). Commercial Potato Production in North America: The Potato Association of America Handbook (PDF). Second Revision of American Potato Journal Supplement Volume 57 and USDA Handbook 267. The Potato Association of America. Archived from the original(PDF) on 16 August 2012.

- Boomgaard, Peter (2003). "In the Shadow of Rice: Roots and Tubers in Indonesian History, 1500–1950". JSTOR 3744936.

- Gauldie, Enid (1981). The Scottish Miller 1700–1900. Pub. John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-067-7.

- Hawkes, J.G. (1990). The Potato: Evolution, Biodiversity & Genetic Resources, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC

- Lang, James (1975). Notes of a Potato Watcher. Texas A&M University Agriculture series. ISBN 978-1-58544-138-9.

- Langer, William L (1975). "American Foods and Europe's Population Growth 1750–1850". JSTOR 3786266.

- McNeill, William H. "How the Potato Changed the World's History." Social Research (1999) 66#1 pp. 67–83. Ebsco, by a leading historian

- McNeill William H (1948). "The Introduction of the Potato into Ireland". S2CID 145099646.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. Black '47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory. (1999). 272 pp.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac, Richard Paping, and Eric Vanhaute, eds. When the Potato Failed: Causes and Effects of the Last European Subsistence Crisis, 1845–1850. (2007). 342 pp. ISBN 978-2-503-51985-2. 15 essays by scholars looking at Ireland and all of Europe

- Reader, John. Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History (2008), 315pp a standard scholarly history

- Salaman, Redcliffe N. (1989) [1949. The History and Social Influence of the Potato, Cambridge University Press.

- Spooner, David M.; McLean, Karen; Ramsay, Gavin; Waugh, Robbie; Bryan, Glenn J. (October 2005). "A single domestication for potato based on multilocus amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (41). PMID 16203994.

- Stevenson, W.R., Loria, R., Franc, G.D., and Weingartner, D.P. (2001) Compendium of Potato Diseases, 2nd ed, Amer. Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN.

- The World Potato Atlas, released by the International Potato Center in 2006 and regularly updated.

- World Geography of the Potato at UGA.edu, released in 1993.

- Zuckerman, Larry. The Potato: How the Humble Spud Rescued the Western World. (1998). 304 pp. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-86547-578-4.

![Production of potatoes (2019)[78]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Production_of_potatoes_%282019%29.svg/622px-Production_of_potatoes_%282019%29.svg.png)