Religious law

Religious law includes

Examples of religiously derived legal codes include Christian canon law (applicable within a wider theological conception in the church, but in modern times distinct from secular state law[3]), Jewish halakha, Islamic sharia, and Hindu law.[4]

Established religions and religious institutions

A

is recognized as the supreme civil ruler.In both theocracies and some religious jurisdictions,

Baháʼí Faith

A few examples of laws and basic religious observances of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas which are considered obligatory for Baháʼís include:

- Recite an obligatory prayer each day. There are three such prayers among which one can be chosen each day.

- Observe a Nineteen Day Fastfrom sunrise to sunset from March 2 through March 20. During this time Baháʼís in good health between the ages of 15 and 70 abstain from eating and drinking.

- Gossip and backbiting are prohibited and viewed as particularly damaging to the individual and their relationships.

Buddhism

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

In Buddhism, Patimokkha is a code of 227 rules and principles followed by Buddhist monks and nuns.[7]

Christianity

Within the framework of

In some

John 1:16-18

— And of his fullness have all we received, and grace for grace. For the law was given by Moses, but grace and truth came by Jesus Christ., KJV

Biblical/Mosaic law

Christian views of the

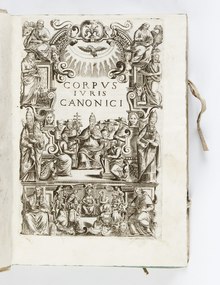

Canon law

Canon law is the body of laws and regulations made by or adopted by ecclesiastical authority for the governance of the Christian organization and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the

Canons of the Apostles

The

Catholic Church

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

Catholicism portal |

The

Positive ecclesiastical laws derive formal authority in the case of universal laws from

It has all the ordinary elements of a mature legal system:[17] laws, courts, lawyers, judges,[17] a fully articulated legal code for the Latin Church as well as a code for the Eastern Catholic Churches,[18] principles of legal interpretation,[19] and coercive penalties.[20] It lacks civilly binding force in most secular jurisdictions. Those who are versed and skilled in canon law, and professors of canon law, are called canonists[21] (or colloquially, canon lawyers).[22] Canon law as a sacred science is called canonistics.

The jurisprudence of Catholic canon law is the complex of legal principles and traditions within which canon law operates, while the philosophy, theology, and fundamental theory of Catholic canon law are the areas of philosophical, theological, and legal scholarship dedicated to providing a theoretical basis for canon law as a legal system and as true law.

In the

Later, they were gathered together into

By the 19th century, this body of legislation included some 10,000 norms, many difficult to reconcile with one another due to changes in circumstances and practice. This situation impelled

The canon law of the Eastern Catholic Churches, which had developed some different disciplines and practices, underwent its own process of codification, resulting in the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches promulgated in 1990 by Pope John Paul II.

The institutions and practices of canon law paralleled the legal development of much of Europe, and consequently both modern Civil law and Common law bear the influences of canon law. Edson Luiz Sampel, a Brazilian expert in canon law, says that canon law is contained in the genesis of various institutes of civil law, such as the law in continental Europe and Latin American countries. Sampel explains that canon law has significant influence in contemporary society.

Currently, all

Orthodox Churches

The Greek-speaking Orthodox have collected canons and commentaries upon them in a work known as the Pēdálion (Greek: Πηδάλιον, "Rudder"), so named because it is meant to "steer" the Church. The Orthodox Christian tradition in general treats its canons more as guidelines than as laws, the

Anglican Communion

In the

Other churches in the

Presbyterian and Reformed Churches

In Presbyterian and Reformed Churches, canon law is known as "practice and procedure" or "church order", and includes the church's laws respecting its government, discipline, legal practice and worship.

Lutheranism

The

The United Methodist Church

The Book of Discipline contains the laws, rules, policies and guidelines for The United Methodist Church. It is revised every four years by the General Conference, the law-making body of The United Methodist Church; the last edition was published in 2016.[24]

Hinduism

Hindu law, a term of colonial origin, is derived from Hindu texts such as the Vedas, Upanishads, Dharmashastras, Puranas, Itihasas, Dharmasutras, Grihya Sutras, Arthashastra and Niti Shastras.

Islam

Muslims believe the sharia is

Sharia deals with many topics addressed by secular law, including

The reintroduction of sharia is a longstanding goal for

Jainism

Jain law or Jaina law refers to the modern interpretation of ancient Jain Law that consists of rules for adoption, marriage, succession and death for the followers of Jainism.[37]

Judaism

The halakhah has developed gradually through a variety of legal and quasi-legal mechanisms, including judicial decisions, legislative enactments, and customary law. The literature of questions to rabbis, and their considered answers, are referred to as Responsa. Over time, as practices develop, codes of Jewish law were written based on Talmudic literature and Responsa. The most influential code, the Shulchan Aruch, guides the religious practice of most Orthodox and some Conservative Jews.

According to rabbinic tradition there are

See also

- Doctrine and Covenants

- Ethics in religion

- Law and religion, the interdisciplinary study of religion and law

- Lawsuits against God

- Morality and religion

- List of national legal systems

- Religious police

- Rule according to higher law

- Rule of law

References

- ^ "In history, systems of law have almost always been based on religion: decisions regarding what was to be lawful among men were taken with reference to the divinity. Unlike other great religions, Christianity has never proposed a revealed law to the State and to society, that is to say a juridical order derived from revelation. Instead, it has pointed to nature and reason as the true sources of law" ("Address of His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI to the Reichstag". Retrieved 2019-12-16.).

- ^ "SUMMA THEOLOGIAE: The moral precepts of the old law (Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 100)". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ Ladislas Orsy, "Towards a Theological Conception of Canon Law" (published in Jordan Hite, T.O.R., & Daniel J. Ward, O.S.B., "Readings, Cases, Materials in Canon Law: A Textbook for Ministerial Students, Revised Edition" (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1990), pg. 11

- ^ Gad Barzilai, Law and Religion, Ashgate, 2007

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- ^ a b c Smith 2008, pp. 159[citation not found]

- ^ "Pāṭimokkha | The Buddhist Monastic Code, Volumes I & II". www.dhammatalks.org. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- Contra Faustum, where he states that the Apostles had given this command in order to unite the heathens and Jews in the one ark of Noah; but that then, when the barrier between Jewish and heathen converts had fallen, this command concerning things strangled and blood had lost its meaning, and was only observed by few. But still, as late as the eighth century, Pope Gregory the Third (731) forbade the eating of blood or things strangled under threat of a penance of forty days. No one will pretend that the disciplinary enactments of any council, even though it be one of the undisputed Ecumenical Synods, can be of greater and more unchanging force than the decree of that first council, held by the Holy Apostles at Jerusalem, and the fact that its decree has been obsolete for centuries in the West is proof that even Ecumenical canons may be of only temporary utility and may be repealed by disuse, like other laws."

- ^ "Canon law". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Apostolic Canons". New Advent. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ "The Ecclesiastical Canons of the Same Holy Apostles". Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol VII. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary, 5th Edition, pg. 771: "Jus canonicum"

- ^ Della Rocca, Manual of Canon Law, pg. 3

- ^ Berman, Harold J. Law and Revolution, pg. 86 & pg. 115

- Dr. Edward N. Peters, CanonLaw.info Home Page, accessed June-11-2013

- ^ Canon 331, 1983 Code of Canon Law

- ^ a b Edward N. Peters, "A Catechist's Introduction to Canon Law" Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine, CanonLaw.info, accessed June-11-2013

- ^ Manual of Canon Law, pg. 49

- ^ "Code of Canon Law: text - IntraText CT". www.intratext.com. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ St. Joseph Foundation newsletter, Vol. 30 No. 7 Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, pg. 3

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary, 5th Edition, pg. 187: "Canonist"

- ^ Berman, Law and Revolution, pg. 288

- ^ F. Bente, ed. and trans., Concordia Triglotta, (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1921), p. i

- ^ Book of Discipline (United Methodist)

- ^ Otto, Jan Michiel (2008). p. 7. "When people refer to the sharia, they are in fact referring to their sharia, in the name of the eternal will of the Almighty God."

- ^ Hamann, Katie (December 29, 2009). "Aceh's Sharia Law Still Controversial in Indonesia". Voice of America. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Iijima, Masako (January 13, 2010). "Islamic Police Tighten Grip on Indonesia's Aceh". Reuters. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "Aceh Sharia Police Loved and Hated". The Jakarta Post.

- ^ Staff (January 3, 2003). "Analysis: Nigeria's Sharia Split". BBC News. Retrieved September 19, 2011. "Thousands of people have been killed in fighting between Christians and Muslims following the introduction of sharia punishments in northern Nigerian states over the past three years".

- ^ Harnischfeger, Johannes (2008) p. 16. "When the Governor of Kaduna announced the introduction of Sharia, although non-Muslims form almost half of the population, violence erupted, leaving more than 1,000 people dead" (p. 189). "When a violent confrontation loomed in February 200?, because the strong Christian minority in Kaduna was unwilling to accept the proposed sharia law, the sultan and his delegation of 18 emirs went to see the governor and insisted on the passage of the bill."

- ^ Mshelizza, Ibrahim (July 28, 2009). "Fight for Sharia Leaves Dozens Dead in Nigeria – Islamic Militants Resisting Western Education Extend Their Campaign of Violence". The Independent. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ "Nigeria in Transition: Recent Religious Tensions and Violence" Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine. PBS.

- ^ Staff (December 28, 2010). "Timeline: Tensions in Nigeria – A Look at the Country's Bouts of Inter-Religious and Ethnic Clashes and Terror Attacks". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved September 19, 2011. "Thousands of people are killed in northern Nigeria as non-Muslims opposed to the introduction of sharia, or Islamic law, fight Muslims who demand its implementation in the northern state of Kaduna.".

- ^ Ibrahimova, Roza (July 27, 2009). "Dozens Killed in Violence in Northern Nigeria" (video (requires Adobe Flash; 00:01:49)). Al Jazeera English. Retrieved September 19, 2011. "The group Boko Haram, which wants to impose sharia (Islamic law) across the country, has attacked police stations and churches."

- ^ Library of Congress Country Studies: Sudan:. "The factors that provoked the military coup, primarily the closely intertwined issues of Islamic law and of the civil war in the south, remained unresolved in 1991. The September 1983 implementation of the sharia throughout the country had been controversial and provoked widespread resistance in the predominantly non-Muslim south. ...Opposition to the sharia, especially to the application of hudud (sing., hadd), or Islamic penalties, such as the public amputation of hands for theft, was not confined to the south and had been a principal factor leading to the popular uprising of April 1985 that overthrew the government of Jaafar an Nimeiri."

- ^ "FRONTLINE/WORLD . Sudan - The Quick and the Terrible . Facts and Stats | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ISBN 9788188677016

Further reading

- Norman Doe. Comparative Religious Law: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Buddhism and Law: An Introduction. Edited by Rebecca Redwood French and Mark A. Nathan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. Pp. 407.- Volume 31. Issue 1.

- Ulanov, M.S., Badmaev, V.N., Holland, E.C. Buddhism and Kalmyk Secular Law in the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries. Inner Asia, 2017, no.19, pp. 297–314.