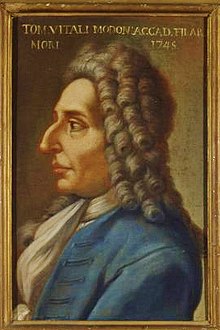

Tomaso Antonio Vitali

Tomaso Antonio Vitali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Tomaso Antonio Vitali 7 March 1663 Bologna, Italy |

| Died | 9 May 1745 (aged 82) Modena, Italy |

| Occupations |

|

Tomaso Antonio Vitali (7 March 1663 – 9 May 1745) was an Italian composer and violinist of the mid to late

Biography

Vitali was born in

Authentic works by Vitali include a set of trio sonatas published as his opus numbers 1 and 2 (1693), sonatas da camera (chamber sonatas), and violin sonatas (including his opus 6)[citation needed] among other works. Among those that have been recorded include all of the op. 1 (on Naxos 8.570182), three of the violin sonatas (on the Swiss label Gallo), and some of the sonatas from the opp. 2 and 4 sets (opus 4, no. 12 on Classica CL 101 from Finland.)

He died at Modena on 9 May 1745.[4]

The chaconne

A

Despite musicological doubts, the piece has been ever popular amongst violinists. For example, Jascha Heifetz chose it, in a "very much arranged and altered version", with organ accompaniment, to open his American debut in Carnegie Hall in 1917.[12] Arrangements of it exist for violin and piano by Ferdinand David and by Léopold Charlier, for violin and organ, for violin and orchestra by Ottorino Respighi, and there are transcriptions of it for viola and piano by Friedrich Hermann (1828-1907) and for cello and piano by Luigi Silva.

Selected discography

- Tomaso Antonio Vitali: Twelve Trio Sonatas Op. 1. Performed by Luigi Cozzolino (violin), Luca Giardini (violin), Bettina Hoffmann (cello), Gianluca Lastraioli (theorbo and guitar), Andrea Perugi (organ and harpsichord). Released in 2006. Naxos 8.570182

References

- ^ "Vitali, Tomaso Antonio". Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Suess 2001, "Introduction".

- ^ Jameson, Michael. "Chaconne for violin & continuo in G minor". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ a b Suess 2001, "(2) Tomaso Antonio Vitali".

- RISM 212001253Chaconnes

- ProQuest 1648503208.

- ^ Greich 1970, p. 39.

- ^ "Baroque Virtuoso" Archived 8 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greich 1970, p. 40.

- ^ Andrew Manze. "Angels & devils of the violin" Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Giovanni Battista Vitali. 1689. "Artificii musicali, Op.13." Modena: Eredi Cassiani, p. 34; p. 28

- ISBN 978-1-317-02164-3.

Sources

- Greich, Wolfgang (1970). "Sein oder nicht sein? Nochmals zur 'Chaconne von Vitali'". JSTOR 41116504.

- Suess, John G. (2001). "Vitali family". ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membershiprequired)

Further reading

- Newman, William S. (1972). The Sonata in the Baroque Era (3rd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Greich, Wolfgang (1965). "Die Chaconne g-Moll: von Vitali?". Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft (in German). 7: 149–152.