Ferrara

Ferrara

Fràra ( Emilian) | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Ferrara | |

From top left: The Castello Estense , Via Giuseppe Mazzini, Braghini-Rossetti Palace, San Giorgio di Ferrara Cathedral, aerial view of the city during its balloon festival, statue to Nicolò III d'Este in Palazzo Municipale, statue to Girolamo Savonarola in Piazza Savonarola. | |

St. George | |

| Saint day | April 23 |

| Website | www |

Ferrara (

History

Antiquity and Middle Ages

The first documented settlements in the area of the present-day Province of Ferrara date from the 6th century BC.

There is uncertainty among scholars about the proposed

Ferrara appears first in a document of the

Early modern

In 1452

The architecture of Ferrara greatly benefited from the genius of Biagio Rossetti, who was requested in 1484 by Ercole I to draft a masterplan for the expansion of the town. The resulting "Erculean Addition" is considered one of the most important examples of Renaissance urban planning[13] and contributed to the selection of Ferrara as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv, v, vi |

| Reference | 733 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

In spite of having entered its golden age, Ferrara was severely hit by a

Upon his death in 1534, Alfonso I was succeeded by his son

Late modern and contemporary

Ferrara, a university city second only to Bologna, remained a part of the

During the last decades of the 1800s and the early 1900s, Ferrara remained a modest trade centre for its large rural hinterland that relied on commercial crops such as

After almost 450 years, another earthquake struck Ferrara in May 2012 causing only limited damage to the historic buildings of the town and no victims.

Geography and climate

The town of Ferrara lies on the southern shores of the

The climate of the Po valley is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa) under the Köppen climate classification, a type of climate commonly referred to as "warm temperate" that features mild winters and hot summers, heavy rains in spring and autumn but there is also a lot of rain even in the driest month of January for Ferrara.[22]

Government

The legislative body of the

The current division of the seats in the city council, after the 2019 local election, is the following:

- Lega Nord – 14

- Democratic Party – 8

- Ferrara Change (centre-right) – 3

- Forza Italia – 2

- Fratelli d'Italia – 1

- Gente a Modo (centre-left) – 1

Cityscape

Architecture

The imposing Este Castle, sited in the very centre of the town, is iconic of Ferrara. A very large manor house featuring four massive bastions and a moat, it was erected in 1385 by architect Bartolino da Novara with the function to protect the town from external threats and to serve as a fortified residence for the Este family.[25] It was extensively renovated in the 15th and 16th centuries.[25]

The

Near the cathedral and the castle also lies the 15th-century city hall, that served as an earlier residence of the Este family, featuring a grandiose marble flight of stairs and two ancient bronze statues of Niccolò III and Borso of Este.[9]

The southern district is the town's oldest, crossed by a myriad of narrow alleys that date back to the

The northern quarter, which was added by Ercole I in 1492–1505 thanks to the master plan of

Parks and gardens

The town is still almost totally encircled by 9 kilometres (6 miles) of ancient brick walls, mostly built between 1492 and 1520.[9] Today the walls, after a careful restoration, make up a large urban park around the town and are a popular destination for joggers and cyclists.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 64,204 | — |

| 1871 | 67,306 | +4.8% |

| 1881 | 70,442 | +4.7% |

| 1901 | 81,301 | +15.4% |

| 1911 | 95,721 | +17.7% |

| 1921 | 106,768 | +11.5% |

| 1931 | 115,628 | +8.3% |

| 1936 | 119,265 | +3.1% |

| 1951 | 133,949 | +12.3% |

| 1961 | 152,654 | +14.0% |

| 1971 | 154,066 | +0.9% |

| 1981 | 149,453 | −3.0% |

| 1991 | 138,015 | −7.7% |

| 2001 | 130,992 | −5.1% |

| 2011 | 132,545 | +1.2% |

| 2021 | 129,872 | −2.0% |

| Source: ISTAT | ||

In 2007, there were 135,369 people residing in Ferrara, of whom 46.8% were male and 53.2% were female. Minors (children ages 18 and younger) totalled 12.28% of the population compared to pensioners who number 26.41%. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06% (minors) and 19.94% (pensioners). The average age of Ferrara residents is 49, compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Ferrara grew by 2.28%, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.85%.[29]

As of 2006[update], 95.59% of the population was

Culture

Jewish community

The Jewish community of Ferrara is the only one in Emilia Romagna with a continuous presence from the Middle Ages to the present day. It played an important role when Ferrara enjoyed its greatest splendor in the 15th and 16th century, with the duke

In 1799, the Jewish community saved the city from sacking by troops of the

Klenau took possession of the town on 21 May, and garrisoned it with a light battalion. The Jewish residents of Ferrara paid 30,000 ducats to prevent the pillage of the city by Klenau's forces; this was used to pay the wages of Gardani's troops.[33] Although Klenau held the town, the French still possessed the town's fortress. After making the standard request for surrender at 08:00, which was refused, Klenau ordered a barrage from his mortars and howitzers. After two magazines caught fire, the commandant was summoned again to surrender; there was some delay, but a flag of truce was sent at 21:00, and the capitulation was concluded at 01:00 the next day. Upon taking possession of the fortress, Klenau found 75 new artillery pieces, plus ammunition and six months worth of provisions.[34]

In 1938, Mussolini's fascist government instituted racial laws reintroducing segregation of Jews which lasted until the end of the German occupation. During the Second World War, 96 of Ferrara's 300 Jews were deported to German concentration and death camps; five survived. The Italian Jewish writer,

During WWII, the Este Castle, adjacent to the Corso Roma, now known as the Corso Martiri della Libertà, was the site of an infamous massacre in 1943.

On December 13, 2017, the first day of

Visual art

During the Renaissance the Este family, well known for its patronage of the arts, welcomed a great number of artists, especially painters, that formed the so-called

Literature

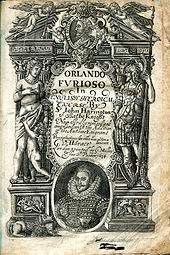

The Renaissance literary men and poets Torquato Tasso (author of Jerusalem Delivered), Ludovico Ariosto (author of the romantic epic poem Orlando Furioso) and Matteo Maria Boiardo (author of the grandiose poem of chivalry and romance Orlando Innamorato) lived and worked at the court of Ferrara during the 15th and 16th century.

The

Religion

Ferrara gave birth to Girolamo Savonarola, the famous medieval Dominican priest and leader of Florence from 1494 until his execution in 1498. He was known for his book burning, destruction of what he considered immoral art, and hostility to the Renaissance. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia).

During the time that Renée of France was Duchess of Ferrara, her court attracted Protestant thinkers such as John Calvin and Olympia Fulvia Morata.[37] The court became hostile to Protestant sympathizers after the marriage of Renée's daughter Anna d'Este to the fervently Catholic Duke of Guise.

Music

The Ferrarese musician Girolamo Frescobaldi was one of the most important composers of keyboard music in the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. His masterpiece Fiori musicali (Musical Flowers) is a collection of liturgical organ music first published in 1635. It became the most famous of Frescobaldi's works and was studied centuries after his death by numerous composers, including Johann Sebastian Bach.[38][39] Maurizio Moro (15??–16??) an Italian poet of the 16th century best known for madrigals is thought to have been born in Ferrara.

Cinema

Ferrara is the birthplace of Italian

In the third season of

Festivals

The

Sport

The town's football team,

Ferrara's basketball team

Cuisine

The culinary tradition of Ferrara features many typical dishes that can be traced back to the Middle Ages, and that sometimes reveals the influence of its important Jewish community.

The signature dish is cappellacci di zucca, special ravioli with a filling of butternut squash, Parmesan and flavored with nutmeg. It is served with a sauce of butter and sage or bolognese sauce. Another peculiar dish, that was allegedly cooked by Renaissance chef Cristoforo di Messisbugo, is pasticcio di maccheroni, a domed macaroni pie, consisting of a crust of sweet dough enclosing macaroni in a Béchamel sauce, studded with porcini mushrooms and ragù alla bolognese.

The traditional Christmas first course is cappelletti, large meat filled ravioli served in chicken broth. It is often followed by salama da sugo, a very big, cured sausage made from a selection of pork meats and spices kneaded with red wine.

Seafood is also an important part of the local tradition, that boast rich fisheries in the Po delta lagoons and Adriatic sea. Pasta with clams and grilled or stewed eel dishes are especially well-known. Popular food items include also zia garlic salami and the traditional coppia bread, protected by the IGP (protected geographical status) label.[49] Not unusual is the typical kosher salami made of goose meat stuffed in goose neck skin.

Local patisserie include spicy pampepato chocolate pie, tenerina, a dark chocolate and butter cake, and zuppa inglese, a chocolate and custard pudding on a bed of sponge cake soaked in Alchermes. The clay terroir of the area, an alluvial plain created by the river Po, is not ideal for wine; a notable exception is Bosco Eliceo (DOC) wine, made from grapes cultivated on the sandy coast line.[50]

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Broni, Italy

Broni, Italy Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina Formia, Italy

Formia, Italy Giessen, Germany

Giessen, Germany Highland Park, United States

Highland Park, United States Kallithea, Greece

Kallithea, Greece Kaufbeuren, Germany

Kaufbeuren, Germany Koper, Slovenia

Koper, Slovenia Krasnodar, Russia

Krasnodar, Russia Lleida, Spain

Lleida, Spain Prague 1, Czech Republic

Prague 1, Czech Republic Saint-Étienne, France

Saint-Étienne, France Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom

Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom Szombathely, Hungary

Szombathely, Hungary

See also

Notes

- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Popolazione 2016" (in Italian). Municipality of Ferrara. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ferrara". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 283.

- ISBN 0719057396.

- ISBN 978-0415673082.

- ^ ISBN 9781274747815.

- ^ ISBN 978-0313307331.

- ^ ISBN 9788836534401.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-0521522632.

- ISBN 978-0521792486.

- ISBN 978-8772890500.

- ISBN 978-0226554037.

- ISBN 978-0582057586.

- ISBN 978-0582491465.

- ISBN 978-9044110920.

- ISBN 978-0230360334.

- ISBN 978-0198287735.

- ISBN 978-88-95014-00-5.

- ISBN 978-0792323556.

- ISBN 978-0521408486.

- ^ "The Municipal Statute of Ferrara (in Italian)". Municipality of Ferrara. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Local self-government authority system under the Italian legislation". Italian Ministry of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-9004243613.

- ISBN 978-0824047894.

- ISBN 978-0415267090.

- ^ Varese, Ranieri (1972). "BRASAVOLA, Pietrobono". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 14. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". Demo.istat.it. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ISBN 978-0262610483.

- ^ Colonel Danilo Oreskovich and 1,300 Croatians of the 2nd Banat battalion, 4,000 Ferrarese auxiliary troops commanded by Count Antonio Gardani, and several hundred local peasants commanded by Major Angelo Pietro Poli. Acerbi. The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition’s Left Wing April – June 1799.

- ^ Acerbi, The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition’s Left Wing April – June 1799.

- ^ Accerbi reports that wages were the equivalent of a daily intake of 21 "Baiocchi" in cash and four in bread. Acerbi, The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition’s Left Wing April – June 1799.

- ^ Acerbi, The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition’s Left Wing April – June 1799; Klenau's force included a battalion of light infantry, a couple battalions of border infantry, a squadron of the Nauendorf Hussars (8th Hussars), and approximately 4,000 armed peasants. For details on Austrian force, see Smith, Ferrara, Data Book, p. 156. Klenau's force also captured 75 guns from the fortress.

- ^ "Once It Imprisoned Jews, Now It's a Museum of Their History in Italy". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ Robin, Diana Maury; Larsen, Anne R; Levin, Carole (2007). Encyclopedia of women in the Renaissance: Italy, France, and England. ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 269.

- ISBN 0-19-816576-5.

- ISBN 0-521-58780-8

- ^ Redazione (November 23, 2019). "Medici 3: ten locations where the series about Lorenzo the Magnificent was filmed". Finestre sull Arte. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "PALIO DI FERRARA". Emiliaromagnaturismo.com. Official tourist information site of the Emilia-Romagna Region. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Clare, Horatio (28 March 2014). "The Palio of Ferrara". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "FERRARA BUSKERS FESTIVAL". Emiliaromagnaturismo.com. Official tourist information site of the Emilia-Romagna Region. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Ferrara Balloons Festival 2017". www.ferrarainfo.com. "Ferrara Terra e Acqua", the official website for Ferrara and its province. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "SPAL RECEIVES BOOST TO FURTHER EXPAND STADIUM". TheStadiumBusiness. 20 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Ferrara's bread – IGP". Ferrara Terra e Acqua. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "The Zia ferrarese Salami". Ferrara Terra e Acqua. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Typical Melon from Emilia". Ferrara Terra e Acqua. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-11879-193-6. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Bosco Eliceo DOC". Enoteca Regionale Emilia-Romagna. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Gemellaggi e patti d'amicizia" (in Italian). Ferrara. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

References

- Acerbi, Enrico. "The 1799 Campaign in Italy: Klenau and Ott Vanguards and the Coalition’s Left Wing April – June 1799". Napoleon Series, Robert Burnham, editor in chief. March 2008. Accessed 30 October 2009.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-88-98086-23-8.

- ISBN 978-88-89248-06-5.

- ISBN 978-88-89248-14-0.

- Gerolamo Melchiorri (2009). ISBN 978-88-89248-21-8.

- SBNIT\ICCU\VEA\0042366.

- ISBN 88-06-18259-5.

- FERRARA entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia italiana

- FERRARA entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia italiana

- Ferrante Borsetti, Ferranti Bolani (1970). Historia almi Ferrariae Gymnasii (in Italian). Vol. 2. Bologna: Forni. SBNIT\ICCU\MIL\0064484.

- AAVV (2008). Servizio protezione flora e fauna oasi e zone protette della Provincia di Ferrara (ed.). I grandi alberi della Provincia di Ferrara (in Italian). Vol. 2. Ferrara: Provincia di Ferrara. SBNIT\ICCU\UFE\0838673.

- AAVV (1998). Atlante cartografico dell'artigianato tipico italiano (in Italian). Rome: ACI, Automobile club d'Italia. SBNIT\ICCU\CAG\1325138.

- Comitato diocesano per il grande giubileo, ed. (2000). Guida del pellegrino in terra ferrarese (in Italian). Milano e Ferrara: Banca Popolare di Milano – Arcidiocesi di FerraraComacchio. SBNIT\ICCU\FER\0180423.

- Ilaria Pavan (2006). Il podestà ebreo. La storia di Renzo Ravenna tra fascismo e leggi razziali (in Italian). Roma-Bari: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-7899-9.

- SBNIT\ICCU\PAR\1233731.

- Antonella Guarnieri (2011). Il fascismo ferrarese. Dodici articoli per raccontarlo. Con un saggio inedito su Edmondo Rossoni (in Italian). Ferrara: Casa Editrice Tresogni. ISBN 978-88-97320-03-6.

- Antonella Guarnieri; Delfina Tromboni; Davide Guarnieri (2014). Lo squadrismo: come lo raccontarono i fascisti, come lo vissero gli antifascisti (PDF). Ferrara: Comune di Ferrara. ISBN 978-88-98786-06-0. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2020-11-22. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- Alessandro Roveri (2000). Ferrara città europea: storia politica e civile dalle origini ai giorni nostri. Ferrara: Este edition. SBN IT\ICCU\FER\0181191. Archived from the originalon 2018-08-18. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- Giulia Aguzzoni e Angela Ghinato (2013). "prefazione di Anna Maria Quarzi, introduzione di Giuseppe Vancini". Arte e bottega (in Italian). Ferrara: Este edition. SBNIT\ICCU\UFE\0979179.

- E. Carina H. Keskitalo, ed. (2010). Developing adaptation policy and practice in Europe: multi-level governance of climate change. Dordrecht: Springer. SBNIT\ICCU\PUV\1423725.

- Biennale ortofrutticola internazionale Ferrara (1969). Eurofrut '69: 21-28 settembre 1969: catalogo ufficiale/4. biennale ortofrutticola internazionale (in Italian). Ferrara: Ente Manifestazioni Ortofrutticole. SBNIT\ICCU\FER\0190433.

- ISBN 978-88-222-5741-3.

- Mary Ellen Snodgrass (2004). Encyclopedia of kitchen history. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. SBNIT\ICCU\BVE\0266908.

External links

- Official Tourism Office Site – in six languages

- Official website

- Search engine and index of websites related to Ferrara Archived 2005-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- The Comunale Theatre

- Ferrara Balloons Festival – the biggest Hot Air Balloons Fiesta in Italy

- Ferrara Under the Stars – The most important Italian summer music festival

- Ferrara Buskers' Festival

- Palazzo dei Diamanti – Ferrara National Museum of Art

- The University of Ferrara

- Local Newspaper