Hagia Sophia

| |

| |

| |

| 41°00′30″N 28°58′48″E / 41.00833°N 28.98000°E | |

| Location | Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Designer | |

| Type |

|

| Material | Ashlar, Roman brick |

| Length | 82 m (269 ft) |

| Width | 73 m (240 ft) |

| Height | 55 m (180 ft) |

| Beginning date | c. 346 |

| Completion date | 360 |

| Dedicated date | 15 February 360 |

| Restored date |

|

| Dedicated to | The Holy Wisdom, a reference to the second person of the Trinity, or Jesus Christ[2] |

| Website | |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

Hagia Sophia (

The current structure was built by the

The religious and spiritual centre of the

After the fall of Constantinople to the

The complex remained a mosque until 1931, when it was closed to the public for four years. It was re-opened in 1935 as a museum under the secular Republic of Turkey, and the building was Turkey's most visited tourist attraction as of 2019[update].[20]

In July 2020, the Council of State annulled the 1934 decision to establish the museum, and the Hagia Sophia was reclassified as a mosque. The 1934 decree was ruled to be unlawful under both Ottoman and Turkish law as Hagia Sophia's waqf, endowed by Sultan Mehmed, had designated the site a mosque; proponents of the decision argued the Hagia Sophia was the personal property of the sultan. The decision to designate Hagia Sophia as a mosque was highly controversial. It resulted in divided opinions and drew condemnation from the Turkish opposition, UNESCO, the World Council of Churches and the International Association of Byzantine Studies, as well as numerous international leaders, while several Muslim leaders in Turkey and other countries welcomed its conversion into a mosque.

History

Church of Constantius II

The first church on the site was known as the Magna Ecclesia (Μεγάλη Ἐκκλησία, Megálē Ekklēsíā, 'Great Church')

The nearby Hagia Irene ("Holy Peace") church was completed earlier and served as cathedral until the Great Church was completed. Besides Hagia Irene, there is no record of major churches in the city-centre before the late 4th century.[24] Rowland Mainstone argued the 4th-century church was not yet known as Hagia Sophia.[27] Though its name as the 'Great Church' implies that it was larger than other Constantinopolitan churches, the only other major churches of the 4th century were the Church of St Mocius, which lay outside the Constantinian walls and was perhaps attached to a cemetery, and the Church of the Holy Apostles.[24]

The church itself is known to have had a timber roof, curtains, columns, and an entrance that faced west.[24] It likely had a narthex and is described as being shaped like a Roman circus.[28] This may mean that it had a U-shaped plan like the basilicas of San Marcellino e Pietro and Sant'Agnese fuori le mura in Rome.[24] However, it may also have been a more conventional three-, four-, or five-aisled basilica, perhaps resembling the original Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.[24] The building was likely preceded by an atrium, as in the later churches on the site.[29]

According to

The building was accompanied by a

Excavations on the western side of the site of the first church under the propylaeum wall reveal that the first church was built atop a road about 8 m (26 ft) wide.[30] According to early accounts, the first Hagia Sophia was built on the site of an ancient pagan temple,[31][32][33] although there are no artefacts to confirm this.[34]

The Patriarch of Constantinople John Chrysostom came into a conflict with Empress Aelia Eudoxia, wife of the emperor Arcadius (r. 383–408), and was sent into exile on 20 June 404. During the subsequent riots, this first church was largely burnt down.[23] Palladius noted that the 4th-century skeuophylakion survived the fire.[35] According to Dark and Kostenec, the fire may only have affected the main basilica, leaving the surrounding ancillary buildings intact.[35]

Church of Theodosius II

A second church on the site was ordered by Theodosius II (r. 402–450), who inaugurated it on 10 October 415.[36] The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, a fifth-century list of monuments, names Hagia Sophia as Magna Ecclesia, 'Great Church', while the former cathedral Hagia Irene is referred to as Ecclesia Antiqua, 'Old Church'. At the time of Socrates of Constantinople around 440, "both churches [were] enclosed by a single wall and served by the same clergy".[25] Thus, the complex would have encompassed a large area including the future site of the Hospital of Samson.[35] If the fire of 404 destroyed only the 4th-century main basilica church, then the 5th century Theodosian basilica could have been built surrounded by a complex constructed primarily during the fourth century.[35]

During the reign of Theodosius II, the emperor's elder sister, the Augusta

The area of the western entrance to the Justinianic Hagia Sophia revealed the western remains of its Theodosian predecessor, as well as some fragments of the Constantinian church.

The basilica was built by architect Rufinus.

At the western end, surviving stone fragments of the structure show there was

The 4th-century skeuophylakion was replaced in the 5th century by the present-day structure, a

A fire started during the tumult of the Nika Revolt, which had begun nearby in the Hippodrome of Constantinople, and the second Hagia Sophia was burnt to the ground on 13–14 January 532. The court historian Procopius wrote:[43]

And by way of shewing that it was not against the Emperor alone that they [the rioters] had taken up arms, but no less against God himself, unholy wretches that they were, they had the hardihood to fire the Church of the Christians, which the people of Byzantium call "Sophia", an epithet which they have most appropriately invented for God, by which they call His temple; and God permitted them to accomplish this impiety, foreseeing into what an object of beauty this shrine was destined to be transformed. So the whole church at that time lay a charred mass of ruins.

— Procopius, De aedificiis, I.1.21–22

- Remains of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia

-

Column and capital with aGreek cross

-

impost block

-

Soffits and cornice

-

Theodosian capital

-

Theodosian capital for a pilaster, one of the few remains of the church of Theodosius II

Church of Justinian I (current structure)

On 23 February 532, only a few weeks after the destruction of the second basilica, Emperor Justinian I inaugurated the construction of a third and entirely different basilica, larger and more majestic than its predecessors.[44] Justinian appointed two architects, mathematician Anthemius of Tralles and geometer and engineer Isidore of Miletus, to design the building.[45][46]

Construction of the church began in 532 during the short tenure of Phocas as

According to

Originally the exterior of the church was covered with marble veneer, as indicated by remaining pieces of marble and surviving attachments for lost panels on the building's western face.[50] The white marble cladding of much of the church, together with gilding of some parts, would have given Hagia Sophia a shimmering appearance quite different from the brick- and plaster-work of the modern period, and would have significantly increased its visibility from the sea.[50] The cathedral's interior surfaces were sheathed with polychrome marbles, green and white with purple porphyry, and gold mosaics. The exterior was clad in stucco that was tinted yellow and red during the 19th-century restorations by the Fossati architects.[51]

The construction is described by Procopius in On Buildings (

Referring to the destruction of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia and comparing the new church with the old, Procopius lauded the Justinianic building, writing in De aedificiis:[43]

... the Emperor Justinian built not long afterwards a church so finely shaped, that if anyone had enquired of the Christians before the burning if it would be their wish that the church should be destroyed and one like this should take its place, shewing them some sort of model of the building we now see, it seems to me that they would have prayed that they might see their church destroyed forthwith, in order that the building might be converted into its present form.

— Procopius, De aedificiis, I.1.22–23

Upon seeing the finished building, the Emperor reportedly said: "Solomon, I have surpassed thee" (

Justinian and

Earthquakes in August 553 and on

According to the history of the patriarch

In 726, the emperor

The basilica suffered damage, first in a great fire in 859, and again in an earthquake on 8 January 869 that caused the collapse of one of the half-domes.[71] Emperor Basil I ordered repair of the tympanas, arches, and vaults.[72]

In his book De caerimoniis aulae Byzantinae ("Book of Ceremonies"), the emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959) wrote a detailed account of the ceremonies held in the Hagia Sophia by the emperor and the patriarch.

Early in the 10th century, the pagan ruler of the Kievan Rus' sent emissaries to his neighbors to learn about Judaism, Islam, and Roman and Orthodox Christianity. After visiting Hagia Sophia his emissaries reported back: "We were led into a place where they serve their God, and we did not know where we were, in heaven or on earth."[73]

In the 940s or 950s, probably around 954 or 955, after the

After the great earthquake of 25 October 989, which collapsed the western dome arch, Emperor

According to the 13th-century Greek historian

In 1181, the daughter of the emperor Manuel I,

Choniates further writes that in 1203, during the

During the

Upon the capture of Constantinople in 1261 by the

On 12 December 1452,

According to

The eventual fall of Constantinople had long been predicted in

From the time of Procopius in the reign of Justinian, the equestrian imperial statue on the

According to

What was the reason that compelled all to flee to the Great Church? They had been listening, for many years, to some pseudo-soothsayers, who had declared that the city was destined to be handed over to the Turks, who would enter in large numbers and would massacre the Romans as far as the Column of Constantine the Great. After this an angel would descend, holding his sword. He would hand over the kingdom, together with the sword, to some insignificant, poor, and humble man who would happen to be standing by the Column. He would say to him: "Take this sword and avenge the Lord's people." Then the Turks would be turned back, would be massacred by the pursuing Romans, and would be ejected from the city and from all places in the west and the east and would be driven as far as the borders of Persia, to a place called the Lone Tree …. That was the cause for the flight into the Great Church. In one hour that famous and enormous church was filled with men and women. An innumerable crowd was everywhere: upstairs, downstairs, in the courtyards, and in every conceivable place. They closed the gates and stood there, hoping for salvation.

— Doukas, XXXIX.18

In accordance with the traditional custom of the time, Sultan Mehmed II allowed his troops and his entourage three full days of unbridled pillage and looting in the city shortly after it was captured. This period saw the destruction of many Orthodox churches;[103] Hagia Sophia itself was looted as the invaders believed it to contain the greatest treasures of the city.[104] Shortly after the defence of the Walls of Constantinople collapsed and the victorious Ottoman troops entered the city, the pillagers and looters made their way to the Hagia Sophia and battered down its doors before storming inside.[105] Once the three days passed, Mehmed was to claim the city's remaining contents for himself.[106][107] However, by the end of the first day, he proclaimed that the looting should cease as he felt profound sadness when he toured the looted and enslaved city.[108][106][109]

Throughout the siege of Constantinople, the trapped people of the city participated in the Divine Liturgy and the Prayer of the Hours at the Hagia Sophia, and the church was a safe-haven and a refuge for many of those who were unable to contribute to the city's defence, including women, children, elderly, the sick and the wounded.[110][111][109] As they were trapped in the church, the many congregants and other refugees inside became spoils-of-war to be divided amongst the triumphant invaders. The building was desecrated and looted, and those who sought shelter within the church were enslaved.[104] While most of the elderly and the infirm, injured, and sick were killed, the remainder (mainly teenage males and young boys) were chained and sold into slavery.[105][109]

Mosque (1453–1935)

As described by Western visitors before 1453, such as the

Before 1481, a small

In the 16th century, Sultan

During the reign of

In 1594 (AH 1004) Mimar (court architect)

In 1717, under the reign of Sultan

Renovation of 1847–1849

The 19th-century restoration of the Hagia Sophia was ordered by Sultan

Eight new gigantic circular-framed discs or

In 1850, the architects Fossati built a new

Outside the main building, the minarets were repaired and altered so that they were of equal height.

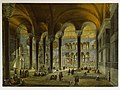

- Gaspare Fossati's Hagia Sophia (lithographs by Louis Haghe)

-

Main (western) façade of Hagia Sophia, seen from courtyard of the madrasa of Mahmud I. Lithograph by Louis Haghe after Gaspard Fossati (1852).

-

South-eastern side, seen from the Imperial Gate of theSultan Ahmed Mosquein the distance. Lithograph by Louis Haghe after Gaspard Fossati (1852).

-

The imperial lodge (b 1850)

-

Gaspare Fossati's 1852 depiction of the Hagia Sophia, after his and his brother's renovation. Lithograph by Louis Haghe.

-

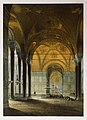

Nave before restoration, facing east

-

Nave and apse after restoration, facing east

-

Nave and entrance after restoration, facing west

-

Narthex, facing north

-

Exonarthex, facing north

-

North aisle from the entrance, facing east

-

North aisle, facing west

-

Nave and south aisle from the north aisle

-

Northern gallery and entrance to the matroneum from the north-west

-

Southern gallery from the south-west

-

Southern gallery from the Marble Door facing west

-

Southern gallery from the Marble Door facing east

Occupation of Istanbul (1918–1923)

In the aftermath of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Constantinople was occupied by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces. On 19 January 1919, the Greek Orthodox Christian military priest Eleftherios Noufrakis performed an unauthorized Divine Liturgy in the Hagia Sophia, the only such instance since the 1453 fall of Constantinople.[127] The anti-occupation Sultanahmet demonstrations were held next to Hagia Sophia from March to May 1919. In Greece, the 500 drachma banknotes issued in 1923 featured Hagia Sophia.[128]

Museum (1935–2020)

In 1935, the first

In 2014, Hagia Sophia was the second most visited museum in Turkey, attracting almost 3.3 million visitors annually.[132]

While use of the complex as a place of worship (mosque or church) was strictly prohibited,[133] in 1991 the Turkish government allowed the allocation of a pavilion in the museum complex (Ayasofya Müzesi Hünkar Kasrı) for use as a prayer room, and, since 2013, two of the museum's minarets had been used for voicing the call to prayer (the ezan) regularly.[134][135]

From the early 2010s, several campaigns and government high officials, notably Turkey's deputy prime minister Bülent Arınç in November 2013, demanded the Hagia Sophia be converted back into a mosque.[136][137][138] In 2015, Pope Francis publicly acknowledged the Armenian genocide, which is officially denied in Turkey. In response, the mufti of Ankara, Mefail Hızlı, said he believed the Pope's remarks would accelerate the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque.[139]

On 1 July 2016, Muslim prayers were held again in the Hagia Sophia for the first time in 85 years.

On 13 May 2017, a large group of people, organized by the Anatolia Youth Association (AGD), gathered in front of Hagia Sophia and prayed the morning prayer with a call for the re-conversion of the museum into a mosque.

Reversion to mosque (2018–present)

Since 2018,

In 2020, Turkey's government celebrated the 567th anniversary of the Conquest of Constantinople with an Islamic prayer in Hagia Sophia. Erdoğan said during a televised broadcast "Al-Fath surah will be recited and prayers will be done at Hagia Sophia as part of conquest festival".[154] In May, during the anniversary events, passages from the Quran were read in the Hagia Sophia. Greece condemned this action, while Turkey in response accused Greece of making "futile and ineffective statements".[155] In June, the head of Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) said that "we would be very happy to open Hagia Sophia for worship" and that if it happened "we will provide our religious services as we do in all our mosques".[141] On 25 June, John Haldon, president of the International Association of Byzantine Studies, wrote an open letter to Erdoğan asking that he "consider the value of keeping the Aya Sofya as a museum".[156]

On 10 July 2020, the decision of the Council of Ministers from 1935 to transform the Hagia Sophia into a museum was annulled by the Council of State, decreeing that Hagia Sophia cannot be used "for any other purpose" than being a mosque and that the Hagia Sophia was property of the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Han Foundation. The council reasoned Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, who conquered Istanbul, deemed the property to be used by the public as a mosque without any fees and was not within the jurisdiction of the Parliament or a ministry council.

On 17 July, Erdoğan announced that the first prayers in the Hagia Sophia would be open to between 1,000 and 1,500 worshippers. He said that Turkey had sovereign power over Hagia Sophia and was not obligated to bend to international opinion.[168]

While the Hagia Sophia has now been rehallowed as a mosque, the place remains open for visitors outside of prayer times. While at the beginning the entrance was free,[169] later the Turkish government decided that, starting from 15 January 2024, the foreign nationals will have to pay an entrance fee.[170]

On 22 July, a turquoise-coloured carpet was laid to prepare the mosque for worshippers;

In April 2022, the Hagia Sophia held its first Ramadan tarawih prayer in 88 years.[175]

International reaction and discussions

Days before the final decision on the conversion was made, Ecumenical Patriarch

Following the Turkish government's decision, UNESCO announced it "deeply regret[ted]" the conversion "made without prior discussion", and asked Turkey to "open a dialogue without delay", stating that the lack of negotiation was "regrettable".[180][160] UNESCO further announced that the "state of conservation" of Hagia Sophia would be "examined" at the next session of the World Heritage Committee, urging Turkey "to initiate dialogue without delay, in order to prevent any detrimental effect on the universal value of this exceptional heritage".[180] Ernesto Ottone, UNESCO's Assistant Director-General for Culture said "It is important to avoid any implementing measure, without prior discussion with UNESCO, that would affect physical access to the site, the structure of the buildings, the site's moveable property, or the site's management".[180] UNESCO's statement of 10 July said "these concerns were shared with the Republic of Turkey in several letters, and again yesterday evening with the representative of the Turkish Delegation" without a response.[180]

The

When President Erdoğan announced that the first Muslim prayers would be held inside the building on 24 July, he added that "like all our mosques, the doors of Hagia Sophia will be wide open to locals and foreigners, Muslims and non-Muslims." Presidential spokesman

On 14 July the prime minister of Greece, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, said his government was "considering its response at all levels" to what he called Turkey's "unnecessary, petty initiative", and that "with this backward action, Turkey is opting to sever links with western world and its values".[207] In relation to both Hagia Sophia and the Cyprus–Turkey maritime zones dispute, Mitsotakis called for European sanctions against Turkey, referring to it as "a regional troublemaker, and which is evolving into a threat to the stability of the whole south-east Mediterranean region".[207] Dora Bakoyannis, Greek former foreign minister, said Turkey's actions had "crossed the Rubicon", distancing itself from the West.[208] On the day of the building's re-opening, Mitsotakis called the re-conversion evidence of Turkey's weakness rather than a show of power.[167]

Armenia's Foreign Ministry expressed "deep concern" about the move, adding that it brought to a close Hagia Sophia's symbolism of "cooperation and unity of humankind instead of clash of civilizations."[209] Catholicos Karekin II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, said the move "violat[ed] the rights of national religious minorities in Turkey"[210] Sahak II Mashalian, the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, perceived as loyal to the Turkish government, endorsed the decision to convert the museum into a mosque. He said, "I believe that believers' praying suits better the spirit of the temple instead of curious tourists running around to take pictures."[211]

In July 2021, UNESCO asked for an updated report on the state of conservation and expressed "grave concern". There were also some concerns about the future of its World Heritage status.[212] Turkey responded that the changes had "no negative impact" on UNESCO standards and the criticism is "biased and political".[213]

Architecture

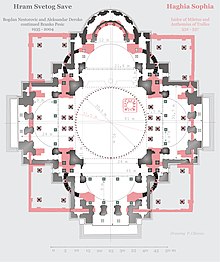

b) Plan of the ground floor (lower half)

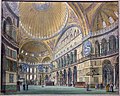

Hagia Sophia is one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture.[8] Its interior is decorated with mosaics, marble pillars, and coverings of great artistic value. Justinian had overseen the completion of the greatest cathedral ever built up to that time, and it was to remain the largest cathedral for 1,000 years until the completion of the cathedral in Seville in Spain.[214]

The Hagia Sophia uses masonry construction. The structure has brick and

Justinian's basilica was at once the culminating architectural achievement of

The vast interior has a complex structure. The nave is covered by a central dome which at its maximum is 55.6 m (182 ft 5 in) from floor level and rests on an arcade of 40 arched windows. Repairs to its structure have left the dome somewhat elliptical, with the diameter varying between 31.24 and 30.86 m (102 ft 6 in and 101 ft 3 in).[218]

At the western entrance and eastern liturgical side, there are arched openings extended by half domes of identical diameter to the central dome, carried on smaller

Each of the four sides of the great square Hagia Sophia is approximately 31 m long,

Floor

The stone floor of Hagia Sophia dates from the 6th century. After the first collapse of the vault, the broken dome was left in situ on the original Justinianic floor and a new floor was laid above the rubble when the dome was rebuilt in 558.[223] From the installation of this second Justinianic floor, the floor became part of the liturgy, with significant locations and spaces demarcated in various ways using different-coloured stones and marbles.[223]

The floor is predominantly made up of

The floor was praised by numerous authors and repeatedly compared to a sea.[114] The Justinianic poet Paul the Silentiary likened the ambo and the solea connecting it to the sanctuary with an island in a sea, with the sanctuary itself a harbour.[114] The 9th-century Narratio writes of it as "like the sea or the flowing waters of a river".[114] Michael the Deacon in the 12th century also described the floor as a sea in which the ambo and other liturgical furniture stood as islands.[114] During the 15th-century conquest of Constantinople, the Ottoman caliph Mehmed is said to have ascended to the dome and the galleries in order to admire the floor, which according to Tursun Beg resembled "a sea in a storm" or a "petrified sea".[114] Other Ottoman-era authors also praised the floor; Tâcîzâde Cafer Çelebi compared it to waves of marble.[114] The floor was hidden beneath a carpet on 22 July 2020.[166]

Narthex and portals

The Imperial Gate, or Imperial Door, was the main entrance between the exo- and esonarthex, and it was originally exclusively used by the emperor.[225][226] A long ramp from the northern part of the outer narthex leads up to the upper gallery.[227]

Upper gallery

The upper gallery, or

.

The northern first floor gallery contains runic graffiti believed to have been left by members of the Varangian Guard.[228] Structural damage caused by natural disasters is visible on the Hagia Sophia's exterior surface. To ensure that the Hagia Sophia did not sustain any damage on the interior of the building, studies have been conducted using ground penetrating radar within the gallery of the Hagia Sophia. With the use of ground-penetrating radar (GPR), teams discovered weak zones within the Hagia Sophia's gallery and also concluded that the curvature of the vault dome has been shifted out of proportion, compared to its original angular orientation.[229]

Dome

The

The great dome at the Hagia Sophia is 32.6 meters (one hundred and seven feet) in diameter and is only 0.61 meters (two feet) thick. The main building materials for the original Hagia Sophia were brick and mortar. Brick aggregate was used to make roofs easier to construct. The aggregate weighs 2402.77 kilograms per cubic meter (150 pounds per cubic foot), an average weight of masonry construction at the time. Due to the materials plasticity, it was chosen over cut stone due to the fact that aggregate can be used over a longer distance.[232] According to Rowland Mainstone, "it is unlikely that the vaulting-shell is anywhere more than one normal brick in thickness".[233]

The weight of the dome remained a problem for most of the building's existence. The original cupola collapsed entirely after the earthquake of 558; in 563 a new dome was built by Isidore the Younger, a nephew of Isidore of Miletus. Unlike the original, this included 40 ribs and was raised 6.1 meters (20 feet), in order to lower the lateral forces on the church walls. A larger section of the second dome collapsed as well, over two episodes, so that as of 2021, only two sections of the present dome, the north and south sides, are from the 562 reconstructions. Of the whole dome's 40 ribs, the surviving north section contains eight ribs, while the south section includes six ribs.[234]

Although this design stabilizes the dome and the surrounding walls and arches, the actual construction of the walls of Hagia Sophia weakened the overall structure. The

Hagia Sophia is famous for the light that reflects everywhere in the interior of the nave, giving the dome the appearance of hovering above. This effect was achieved by inserting forty windows around the base of the original structure. Moreover, the insertion of the windows in the dome structure reduced its weight.[235]

Buttresses

Numerous buttresses have been added throughout the centuries. The flying buttresses to the west of the building, although thought to have been constructed by the Crusaders upon their visit to Constantinople, were actually built during the Byzantine era. This shows that the Romans had prior knowledge of flying buttresses, which can also be seen at in Greece, at the Rotunda of Galerius in Thessaloniki, at the monastery of Hosios Loukas in Boeotia, and in Italy at the octagonal basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.[235] Other buttresses were constructed during the Ottoman times under the guidance of the architect Sinan. A total of 24 buttresses were added.[236]

Minarets

The minarets were an Ottoman addition and not part of the original church's Byzantine design. They were built for notification of invitations for prayers (adhan) and announcements. Mehmed had built a wooden minaret over one of the half domes soon after Hagia Sophia's conversion from a cathedral to a mosque. This minaret does not exist today. One of the minarets (at southeast) was built from red brick and can be dated back from the reign of Mehmed or his successor Beyazıd II. The other three were built from white limestone and sandstone, of which the slender northeast column was erected by Bayezid II and the two identical, larger minarets to the west were erected by Selim II and designed by the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan. Both are 60 m (200 ft) in height, and their thick and massive patterns complete Hagia Sophia's main structure. Many ornaments and details were added to these minarets on repairs during the 15th, 16th, and 19th centuries, which reflect each period's characteristics and ideals.[237][238]

Notable elements and decorations

Originally, under Justinian's reign, the interior decorations consisted of abstract designs on marble slabs on the walls and floors as well as mosaics on the curving vaults. Of these mosaics, the two archangels Gabriel and Michael are still visible in the spandrels (corners) of the bema. There were already a few figurative decorations, as attested by the late 6th-century ekphrasis of Paul the Silentiary, the Description of Hagia Sophia. The spandrels of the gallery are faced in inlaid thin slabs (opus sectile), showing patterns and figures of flowers and birds in precisely cut pieces of white marble set against a background of black marble. In later stages, figurative mosaics were added, which were destroyed during the iconoclastic controversy (726–843). Present mosaics are from the post-iconoclastic period.

Apart from the mosaics, many figurative decorations were added during the second half of the 9th century: an image of Christ in the central dome; Eastern Orthodox saints, prophets and

-

The Loge of the Empress. The columns are made of green Thessalian stone

-

Verd antique columns and disc in the empress's loggia

-

Marble Door

-

The wishing column

Loggia of the Empress

The

Lustration urns

Two huge marble lustration (ritual purification) urns were brought from Pergamon during the reign of Sultan Murad III. They are from the Hellenistic period and carved from single blocks of marble.[19]

Marble Door

The Marble Door inside the Hagia Sophia is located in the southern upper enclosure or gallery. It was used by the participants in synods, who entered and left the meeting chamber through this door. It is said[by whom?] that each side is symbolic and that one side represents heaven while the other represents hell. Its panels are covered in fruits and fish motifs. The door opens into a space that was used as a venue for solemn meetings and important resolutions of patriarchate officials.[242]

The Nice Door

The Nice Door is the oldest architectural element found in the Hagia Sophia dating back to the 2nd century BC. The decorations are of reliefs of geometric shapes as well as plants that are believed to have come from a pagan temple in

Imperial Gate

The Imperial Gate is the door that was used solely by the Emperor and his personal bodyguard and retinue.[226] It is the largest door in the Hagia Sophia and has been dated to the 6th century. It is about 7 meters long and Byzantine sources say it was made with wood from Noah's Ark.[244]

In April 2022, the door was vandalised by unknown assailant(s). The incident became known after the Association of Art Historians published a photo with the destruction. The Greek Foreign Ministry condemned the incident, while Turkish officials claimed that "a citizen has taken a piece of the door" and started an investigation.[245]

Wishing column

At the northwest of the building, there is a column with a hole in the middle covered by bronze plates. This column goes by different names; the "perspiring" or "sweating column", the "crying column", or the "wishing column". Legend states that it has been moist since the appearance of

The Viking Inscription

In the southern section of Hagia Sophia, a 9th-century

Mosaics

The first mosaics which adorned the church were completed during the reign of

During the

19th-century restoration

Following the building's conversion into a mosque in 1453, many of its mosaics were covered with plaster, due to Islam's ban on representational imagery. This process was not completed at once, and reports exist from the 17th century in which travellers note that they could still see Christian images in the former church. In 1847–1849, the building was restored by two

One mosaic they documented is

-

Imperial gate mosaic

-

Southwestern entrance mosaic with Justinian the Great (left) and Constantine the Great (right) with the Virgin Mary in the center

-

Apse mosaic of the Virgin Mary and Christ the Child.

-

TheEmpress Zoemosaic

-

The Comnenus mosaic

-

TheDeësismosaic

-

Mosaic in the northern tympanum depicting Saint John Chrysostom

-

Detail of the Christ Pantocrator mosaic, also known as the Deësis mosaic.

-

a Seraph angel. 13th century CE.

20th-century restoration

Many mosaics were uncovered in the 1930s by a team from the Byzantine Institute of America led by Thomas Whittemore. The team chose to let a number of simple cross images remain covered by plaster but uncovered all major mosaics found.

Because of its long history as both a church and a mosque, a particular challenge arises in the restoration process. Christian iconographic mosaics can be uncovered, but often at the expense of important and historic Islamic art. Restorers have attempted to maintain a balance between both Christian and Islamic cultures. In particular, much controversy rests upon whether the Islamic calligraphy on the dome of the cathedral should be removed, in order to permit the underlying Pantocrator mosaic of Christ as Master of the World to be exhibited (assuming the mosaic still exists).[254]

The Hagia Sophia has been a victim of natural disasters that have caused deterioration to the buildings structure and walls. The deterioration of the Hagia Sophia's walls can be directly attributed to salt crystallization. The crystallization of salt is due to an intrusion of rainwater that causes the Hagia Sophia's deteriorating inner and outer walls. Diverting excess rainwater is the main solution to the deteriorating walls at the Hagia Sophia.[255]

Built between 532 and 537, a subsurface structure under the Hagia Sophia has been under investigation, using LaCoste-Romberg

Imperial Gate mosaic

The Imperial Gate mosaic is located in the

Southwestern entrance mosaic

The southwestern entrance mosaic, situated in the tympanum of the southwestern entrance, dates from the reign of

Apse mosaics

The mosaic in the

Guillaume-Joseph Grelot, who had travelled to Constantinople, in 1672 engraved and in 1680 published in Paris an image of the interior of Hagia Sophia which shows the apse mosaic indistinctly.[261] Together with a picture by Cornelius Loos drawn in 1710, these images are early attestations of the mosiac before it was covered towards the end of the 18th century.[261] The mosaic of the Virgin and Child was rediscovered during the restorations of the Fossati brothers in 1847–1848 and revealed by the restoration of Thomas Whittemore in 1935–1939.[261] It was studied again in 1964 with the aid of scaffolding.[261][262]

It is not known when this mosaic was installed.

Other scholars have favoured earlier or later dates for the present mosaic or its composition. Nikolaos Oikonomides pointed out that Photius's homily refers to a standing portrait of the Theotokos – a Hodegetria – while the present mosaic shows her seated.[268] Likewise, a biography of the patriarch Isidore I (r. 1347–1350) by his successor Philotheus I (r. 1353–1354, 1364–1376) composed before 1363 describes Isidore seeing a standing image of the Virgin at Epiphany in 1347.[261] Serious damage was done to the building by earthquakes in the 14th century, and it is possible that a standing image of the Virgin that existed in Photius's time was lost in the earthquake of 1346, in which the eastern end of Hagia Sophia was partly destroyed.[269][261] This interpretation supposes that the present mosaic of the Virgin and Child enthroned is of the late 14th century, a time in which, beginning with Nilus of Constantinople (r. 1380–1388), the patriarchs of Constantinople began to have official seals depicting the Theotokos enthroned on a thokos.[270][261]

Still other scholars have proposed an earlier date than the later 9th century. According to George Galavaris, the mosaic seen by Photius was a Hodegetria portrait which after the earthquake of 989 was replaced by the present image not later than the early 11th century.

More recently, analysis of a

The portraits of the archangels Gabriel and Michael (largely destroyed) in the bema of the arch also date from the 9th century. The mosaics are set against the original golden background of the 6th century. These mosaics were believed to be a reconstruction of the mosaics of the 6th century that were previously destroyed during the iconoclastic era by the Byzantines of that time, as represented in the inaugural sermon by the patriarch Photios. However, no record of figurative decoration of Hagia Sophia exists before this time.[271]

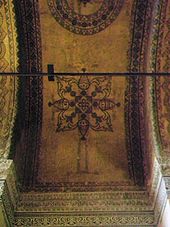

Emperor Alexander mosaic

The Emperor Alexander mosaic is not easy to find for the first-time visitor, located on the second floor in a dark corner of the ceiling. It depicts the emperor Alexander in full regalia, holding a scroll in his right hand and a globus cruciger in his left. A drawing by the Fossatis showed that the mosaic survived until 1849 and that Thomas Whittemore, founder of the Byzantine Institute of America who was granted permission to preserve the mosaics, assumed that it had been destroyed in the earthquake of 1894. Eight years after his death, the mosaic was discovered in 1958 largely through the researches of Robert Van Nice. Unlike most of the other mosaics in Hagia Sophia, which had been covered over by ordinary plaster, the Alexander mosaic was simply painted over and reflected the surrounding mosaic patterns and thus was well hidden. It was duly cleaned by the Byzantine Institute's successor to Whittemore, Paul A. Underwood.[272][273]

Empress Zoe mosaic

The Empress Zoe mosaic on the eastern wall of the southern gallery dates from the 11th century. Christ Pantocrator, clad in the dark blue robe (as is the custom in Byzantine art), is seated in the middle against a golden background, giving his blessing with the right hand and holding the

Comnenus mosaic

The Comnenus mosaic, also located on the eastern wall of the southern gallery, dates from 1122. The Virgin Mary is standing in the middle, depicted, as usual in Byzantine art, in a dark blue gown. She holds the Christ Child on her lap. He gives his blessing with his right hand while holding a scroll in his left hand. On her right side stands emperor

Deësis mosaic

The

Northern tympanum mosaics

The northern tympanum mosaics feature various saints. They have been able to survive due to their high and inaccessible location. They depict Patriarchs of Constantinople John Chrysostom and Ignatios of Constantinople standing, clothed in white robes with crosses, and holding richly jewelled Bibles. The figures of each patriarch, revered as saints, are identifiable by labels in Greek. The other mosaics in the other tympana have not survived probably due to the frequent earthquakes, as opposed to any deliberate destruction by the Ottoman conquerors.[278]

Dome mosaic

The dome was decorated with four non-identical figures of the six-winged angels which protect the Throne of God; it is uncertain whether they are seraphim or cherubim. The mosaics survive in the eastern part of the dome, but since the ones on the western side were damaged during the Byzantine period, they have been renewed as frescoes. During the Ottoman period each seraph's (or cherub's) face was covered with metallic lids in the shape of stars, but these were removed to reveal the faces during renovations in 2009.[279]

Other burials

- Selim II (1524–15 December 1574)

- Murad III 1546–1595

- Mustafa I (c. 1600–20 January 1639), in the courtyard.

- Enrico Dandolo (c. 1107–June 1205), in the east gallery.

- Gli (c. 2004–7 November 2020), in the garden.

Works influenced by the Hagia Sophia

Many buildings have been modeled on the Hagia Sophia's core structure of a large central dome resting on pendentives and buttressed by two semi-domes.

Byzantine churches influenced by the Hagia Sophia include the Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki, and the Hagia Irene. The latter was remodeled to have a dome similar to the Hagia Sophia's during the reign of Justinian.

Several

As with Ottoman mosques, several churches based on the Hagia Sophia include four semi-domes rather than two, such as the

Several churches combine elements of the Hagia Sophia with a Latin cross plan. For instance, the

Synagogues based on the Hagia Sophia include the Congregation Emanu-El (San Francisco),[287] Great Synagogue of Florence, and Hurva Synagogue.

Gallery

-

Detail of the columns

-

Detail of the columns

-

Six patriarchs mosaic in the southern tympanum as drawn by the Fossati brothers

-

Moasics as drawn by the Fossati brothers

-

Guillaume-Joseph Grelot's engraving 1672, looking east and showing the apse mosaic

-

Guillaume-Joseph Grelot's engraving 1672, looking west

-

Interior of the Hagia Sophia by John Singer Sargent, 1891

-

Photograph bySébah & Joaillier, c. 1900–1910

-

Watercolour of the interior by Philippe Chaperon, 1893

-

Detail of relief on the Marble Door.

-

Imperial Gate from the nave

-

19th-century cenotaph of Enrico Dandolo, Doge of Venice, and commander of the 1204 Sack of Constantinople

-

Gate of the külliye, by John Frederick Lewis, 1838

-

Fountain of Ahmed III from the gate of the külliye, by John Frederick Lewis, 1838

-

Southern side of Hagia Sophia, looking east, by John Frederick Lewis, 1838

-

From Verhandeling van de godsdienst der Mahometaanen, by Adriaan Reland, 1719

-

Hagia Sophia from the south-west, 1914

-

Hagia Sophia in the snow, December 2015

-

Maschinengewehr 08 mounted on a minaret during World War II

See also

- Runic inscriptions in Hagia Sophia

- List of Byzantine inventions

- List of tallest domes

- List of largest monoliths

- List of oldest church buildings

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- List of Turkish Grand Mosques

- Conversion of non-Islamic places of worship into mosques

References

Notes

Citations

- S2CID 193099976.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4.(the second entity of the Trinity) or, alternatively, Christ as the Logos incarnate.

Hagia Sophia was consecrated on December 27, 537, five years after construction had begun. The church was dedicated to the Wisdom of God, referring to the Logos

- ^ Eyice, Semavi (1991). "Ayasofya" [Hagia Sophia]. İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 4. Istanbul: Turkish Diyanet Foundation. pp. 206–210.

- OCLC 607531385.

- ISBN 978-0-495-46740-3.

- S2CID 163442071.

- ISBN 978-0-313-35967-5.

Hagia Sophia, or the Church of Holy Wisdom, is one of the world's most spectacular churches, representing not only great beauty, but also masterful engineering.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-305304-2.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (22 August 1993). "Center of Ottoman Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ a b c Heinle & Schlaich 1996

- ^ Cameron 2009.

- ^ Meyendorff 1982.

- ^ a b Janin (1953), p. 471.

- ISBN 978-0-521-66738-8.

- ISBN 978-0-664-25652-4.

- ^ Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 112.

- ^ Jarus, Owen (1 March 2013). "Hagia Sophia: Facts, History & Architecture". livescience.com. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia". ArchNet. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 91.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia still Istanbul's top tourist attraction". hurriyet.

- ^ Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 84.

- ^ Alessandro E. Foni; George Papagiannakis; Nadia Magnentat-Thalmann. "Virtual Hagia Sophia: Restitution, Visualization and Virtual Life Simulation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Janin (1953), p. 472.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78925-030-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- ^ Patria of Constantinople

- ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- ^ Ahmad, Tufail. "Hagia Sophia History | Explore and Learn About This Monument". Hagia Sophia Tickets. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78925-030-5.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia". Hagia Sophia | History, Facts, & Significance. Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 August 2023.

The original church on the site of the Hagia Sophia is said to have been ordered to be built by Constantine I in 325 on the foundations of a pagan temple.

- ISBN 978-1-4408-5147-6.

- ISBN 978-1-884964-02-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78925-030-5.

- OCLC 1206400173.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, retrieved 1 October 2020

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, retrieved 1 October 2020

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9, retrieved 1 October 2020

- ISBN 978-960-8326-14-9.

- ^ Theodosius, Earlier Second Church Ordered by I. I.; Rufinus, Built by Architect; Justinian, Current Church was Ordered by Emperor; Tralles, Designed by Greek Scientists Isidore of Miletus Anthemius of. "Exterior, Walls and Architectural Elements".

Earlier second church ordered by Theodosius II, built by architect Rufinus, current Church was ordered by Emperor Justinian and designed by Greek scientists Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles

- ^ ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- ^ a b c "Book I (beginning)". The Buildings of Procopius. Loeb Classical Library. 1940. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- S2CID 162336421.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-6627-5.

- ^ Heath, Thomas Little (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 02 (11th ed.). p. 93.

- ^ S2CID 162336421.

- ^ a b John Lydus, De Magistratibus reipublicae Romanae III.76

- ^ Evagrius Scholasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica IV.30

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78925-030-5.

- ^ Teteriatnikov, Natalia (1998). Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The Fossati restoration and the work of the Byzantine Institute. Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. p. 17.

- ISBN 978-0-300-05296-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8478-0615-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7139-9997-6.

- ^ a b c d Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 86.

- ^ "The Chronicle of John Malalas," Bk 18.86 Translated by E. Jeffreys, M. Jeffreys, and R. Scott. Australian Association of Byzantine Studies, 1986 vol 4.

- ^ "The Chronicle of Theophones Confessor: Byzantine and Near Eastern History AD 284–813." Translated with commentary by Cyril Mango and Roger Scott. AM 6030 p. 316, with this note: Theophanes' precise date should be accepted.

- S2CID 159951797.

- ^ Stroth (2021), esp. pp. 19–53.

- ^ Janin, Raymond (1950). Constantinople Byzantine (in French) (1 ed.). Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines. p. 41.

- ^ "Haghia Sophia". Istanbul /: Emporis. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Baalbek keeps its secrets". stoneworld.

- ISBN 978-3-11-023907-2.

- OCLC 318874086.

- ^ S2CID 200105105, retrieved 20 October 2020

- S2CID 201011125, retrieved 20 October 2020

- S2CID 199934427, retrieved 20 October 2020

- ^ S2CID 199944450, retrieved 20 October 2020

- S2CID 200995315, retrieved 20 October 2020

- JSTOR 1291219.

- ^ , retrieved 19 June 2021

- .

- ISBN 9780300246063

- ^ JSTOR 1291660.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, retrieved 17 October 2020

- JSTOR 41036130.

- ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4, retrieved 17 October 2020

- ISBN 978-0-19-959660-7, retrieved 17 October 2020

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-89720-0.

- JSTOR 3592516.

- ^ Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 87.

- ^ a b c d Mamboury (1953) p. 287

- ISBN 978-1-315-59054-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8.

- ISBN 978-1-135-01469-8.

- ISBN 978-0-429-89969-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-6319-5.

- ISBN 978-0-19-088329-4.

- ^ Gallo, Rudolfo (1927). "La tomba di Enrico Dandolo in Santa Sofia a Constantinople". Rivista Mensile della Citta di Venezia. 6: 270–83.

- S2CID 191369605.

- ISBN 978-1-4094-1064-5.

- ISBN 978-3-030-16684-7, retrieved 20 October 2020

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4094-1064-5.

- ^ a b c Kraft, András (2012). "Constantinople in Byzantine Apocalyptic Thought" (PDF). Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU. 18: 25–36. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ JSTOR 1291359.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4094-1064-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4094-1064-5.

- ^ "Fall of Constantinople". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b Nicol. The End of the Byzantine Empire, p. 90.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7131-6250-9.

- JSTOR 1291293.

- ^ a b c Calian, Florin George (25 March 2021). "The Hagia Sophia and Turkey's Neo-Ottomanism". The Armenian Weekly. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Runciman. The Fall of Constantinople, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261–1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972, p. 389.

- ISBN 978-90-04-32580-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- ^ S2CID 194078403.

- Tafur, Pero (1926). Travels and Adventures, 1435–1439. Trans. M. Letts. London: G. Routledge. pp. 138–48.

- ^ G. Gerola, "Le vedute di Costantinopoli di Cristoforo Buondemonti," SBN 3 (1931): 247–79.

- ^ Mamboury (1953), p. 288.

- ^ Necipoĝlu (2005), p. 13

- ^ Boyar & Fleet (2010), p. 145

- ^ Gökovali, Şadan. Istanbul. Istanbul: Ticaret Matbaacilik T.A.Ş. pp. 22–23.

- ISBN 978-90-5809-642-5.

- ^ a b c d Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 93.

- ^ "Facts About Hagia Sophia | Discover A Historic Masterpiece!". hagiasophiatickets.com. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Fossati brothers". Turkish Cultural Foundation. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ Admin (11 September 2020). "Architectural Adventure of Hagia Sophia". Architecture News. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Stivaktakis, Anthony E. (27 February 2004). "The Last Divine Liturgy in Hagia Sophia of 1919". www.johnsanidopoulos.com. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "500 Drachmai". Numista. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Tarihin aktığı takvim..." www.ntv.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- OCLC 801099151.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Top 10: Turkey's most visited museums". Hürriyet Daily News. 10 November 2014.

- ^ "İstanbul Tanıtımı – Ayasofya Müzesi". Istanbul. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Ayasofya'nın 4 minaresinden 5 vakit ezan sesi yükseliyor: Ayasofya Müzesi'nin ibadete açık olan bölümü Hünkar Kasrı'na, Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı tarafından uzun yıllardan sonra ilk kez asaleten imam atandı" (in Turkish). Anadolu Agency. 20 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Ayasofya'da her ezan okuduğunda ilk günkü heyecanı yaşıyor: Büyük Ayasofya Camisi İmam Hatibi Kurra Hafız Önder Soy, Ayasofya'da 4 yıldır ilk günkü heyecanıyla görevini yapıyor" (in Turkish). Anadolu Agency. 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Call to reinstate Hagia Sophia as mosque". Financial Times. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Greece angered over Turkish Deputy PM's Hagia Sophia remarks". Hürriyet. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Turkey: Pressure mounts for Hagia Sophia to be converted into mosque". Christian Today. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Pope's remarks 'to accelerate Hagia Sophia's conversion into mosque'". Hürriyet Daily News. 16 April 2015.

- ^ "First call to prayer inside Istanbul's Hagia Sophia in 85 years". Hürriyet.

- ^ a b "Turkish politics heats up over Hagia Sophia". hurriyetdailynews. 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Court declares Hagia Sophia a 'monument museum'". hurriyetdailynews. 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia imam: part of Erdogan's Islamization drive?". Deutsche Welle. 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Muslim group prays in front of Hagia Sophia to demand re-conversion into mosque". Hürriyet.

- ^ "Turkey rejects Greek criticism of Hagia Sophia prayers". Hürriyet.

- ^ a b c Gall, Carlotta (10 July 2020). "Turkish Court Clears Way for Hagia Sophia to Be Used as a Mosque Again". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkish President Erdoğan recites Islamic prayer at the Hagia Sophia". Hürriyet. April 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia's status to be changed to mosque: Erdoğan". Hürriyet.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia: Controversy as Erdogan says museum and former cathedral will become a mosque". Euronews.

- ^ "UNESCO "halts" Erdogan's plans to turn the Hagia Sophia into Mosque". Daily Hellas. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Milli Gazete | Erdoğan Administration Takes Control Of Istanbul's Historic Topkapı Palace". en.milligazete.com.tr. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Erdoğan administration takes control of Istanbul's historic Topkapı Palace". Ahval. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip (6 September 2019). "Presidential Decree" (PDF). Resmî Gazete (in Turkish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Turkey goes back to the future as Hagia Sophia set for Islamic prayers". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkey refutes Greece on Quran session in Hagia Sophia – Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Byzantine News, Issue 33, July 2020". us17.campaign-archive.com. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Making the Hagia Sophia a mosque is a political slap in the face for the West". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkish court rules 1934 conversion of Hagia Sophia into museum illegal". Turkish court rules 1934 conversion of Hagia Sophia into museum illegal. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Ayasofya'yı camiden müzeye dönüştüren Bakanlar Kurulu kararı iptal edildi". www.aa.com.tr.

- ^ a b c d e "Turkey turns iconic Istanbul museum into mosque". BBC News. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b Avundukluoğlu, Muhammet Emin (11 July 2020). "'Hagia Sophia decision ends our nation's longing'". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia converted into mosque as Erdoğan signs decree". hurriyetdailynews. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia icons to be preserved: Presidential spokesperson". hurriyetdailynews. 12 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "İnsanlık mirasına dair kararlar iktidarın politik oyunlarına göre alınamaz" [Decisions on human heritage cannot be made on the basis of political games played by the government]. www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Istanbul mayor supports Hagia Sophia conversion move, 'as long as it benefits Turkey'". hurriyetdailynews. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Hagia Sophia opens to Muslims for Friday prayers". BBC News. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "First Friday prayers at Hagia Sophia for 86 years". BBC News. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Cagatay Zontur, Erdogan (17 July 2020). "Hagia Sophia a matter of Turkey's sovereignty: Erdogan". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ "Russian tourists to benefit from Hagia Sophia status change". Russian tourists to benefit from Hagia Sophia status change. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Foreign visitors to pay entrance fee at Hagia Sophia". hurriyetdailynews. November 2023. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Turkey will cover Hagia Sophia mosaics during prayers - ruling party spokesman". Reuters. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "The mosaics of the Virgin Mary in Hagia Sophia are hidden with white curtains – How Erdogan set up the fiesta". Orthodox Times. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Erdoğan invites Pope Francis to the inauguration of Hagia Sophia Mosque". romereports. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (15 July 2020). "Erdogan Signs Decree Allowing Hagia Sophia to Be Used as a Mosque Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkiye's Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque to hold 1st tarawih prayer in 88 years". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew about Hagia Sophia". www.ecupatria.org/. 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Orthodox Patriarch says turning Istanbul's Hagia Sophia into mosque would be divisive". Reuters. 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Заявление Патриарха Московского и всея Руси Кирилла в связи с ситуацией относительно Святой Софии". www.patriarchia.ru (in Russian). 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Russian church leader says calls to turn Hagia Sophia into mosque threaten Christianity". Reuters. 6 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "UNESCO statement on Hagia Sophia, Istanbul". UNESCO. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "WCC letter to President Erdogan to keep Hagia Sophia as the shared heritage of humanity". www.oikoumene.org. 11 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Church body wants Hagia Sophia decision reversed". BBC News. 11 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b "World Council of Churches "dismayed" at Hagia Sophia shift". AP News. 11 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Pope Francis: 'I think of Hagia Sophia, and I am very saddened'". www.vaticannews.va. 12 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- LaPresse. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Pope 'pained' by Hagia Sophia mosque decision". BBC News. 12 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkey: Statement by the High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell on the decision regarding Hagia Sophia". EEAS – European External Action Service – European Commission. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Stearns, Jonathan (13 July 2020). "EU Urges Turkey to 'Reverse' Hagia Sophia Reconversion Plan". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Casert, Raf; Fraser, Suzan; Gatopoulos, Derek (13 July 2020). "EU, Turkey clash over Hagia Sophia, Mediterranean drilling". AP NEWS. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "World reacts to Turkey reconverting Hagia Sophia into a mosque". Al Jazeera. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Greece pushes for sanctions against Turkey, but EU insists on dialogue". EURACTIV. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Kucukgocmen, Ali; Butler, Daren (13 July 2020). "Turkey will cover Hagia Sophia mosaics during prayers – ruling party spokesman". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Firat, Esat (13 July 2020). "Israeli group burns Turkish flag over Hagia Sophia move". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Cagatay Zontur, Erdogan (14 July 2020). "Turkey condemns burning of Turkish flag in E.Jerusalem". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b Aytekin, Emre (11 July 2020). "Northern Cyprus content with Hagia Sophia decision". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Kursun, Muhammet; Salari, Elaheh (13 July 2020). "Iran praises Turkey's reopening of Hagia Sophia mosque". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Teslova, Elena (13 July 2020). "Russia: Hagia Sophia status 'Turkey's internal affair'". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ "Why did Moscow call Ankara's Hagia Sophia decision "Turkey's internal affair"?". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Yusuf, Ahmed; Asmar, Ahmed (13 July 2020). "Arabs hail Turkey's reopening of Hagia Sophia mosque". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Yildiz, Hamdi (11 July 2020). "Hamas movement supports Hagia Sophia decision". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Latif, Aamir (11 July 2020). "Pakistani lawmaker hails Turkey's Hagia Sophia move". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Kavak, Gokhan (13 July 2020). "South African Muslims hail Turkey's Hagia Sophia move". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Erdem, Omer (11 July 2020). "Mauritania rejoices opening of Hagia Sophia as mosque". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Mufti of Egypt says Turkey's Hagia Sophia mosque conversion is 'forbidden'". 18 July 2020.

- ^ Kara Aydin, Havva (11 July 2020). "Turkish spokesman: Hagia Sophia icons to be preserved". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Kucukgocmen, Ali; Butler, Daren (13 July 2020). "Turkey will inform UNESCO about Hagia Sophia moves – minister". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b Kambas, Michele (14 July 2020). "Greece says Turkey is being 'petty' over Hagia Sophia". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Koutantou, Angeliki; Maltezou, Renee; Kambas, Michele (10 July 2020). "Greece condemns Turkey's decision to convert Hagia Sophia into mosque". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Comment by the Spokesperson of the Foreign Ministry of Armenia on changing the status of Hagia Sophia by the decision of the Turkish authorities". mfa.am. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia. 11 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021.

- ^ "The Reflections of His Holiness Karekin II, Catholicos of All Armenians; on the Decision of the Turkish Authorities to turn the Hagia Sophia Cathedral-Museum into a Mosque". armenianchurch.org. Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 14 July 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Armenian Patriarch backs opening Hagia Sophia to worship". Hürriyet Daily News. 14 June 2020. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021.

- ^ Romey, Kristin (13 July 2020). "Hagia Sophia stripped of museum status, paving its return to a mosque". National Geographic.

- ^ "Turkey hits back at UNESCO concern over Hagia Sophia". dw.com. 24 July 2021.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. p. 513.

- ISSN 0267-7261.

- ^ Sqour, Saqer (5–6 May 2016). Influence of Hagia Sophia on the Construction of Dome in Mosque Architecture (PDF). 8th International Conference on Latest Trends in Engineering and Technology (ICLTET'2016). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- S2CID 193354724.

- .

- ^ "Helge Svenshon 2010: Das Bauwerk als "Aistheton Soma" – Eine Neuinterpretation der Hagia Sophia im Spiegel antiker Vermessungslehre und angewandter Mathematik. In: Falko Daim · Jörg Drauschke (Hrsg.) Byzanz – das Römerreich im Mittelalter Teil 2, 1 Schauplätze, Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Forschungsinstitut für Vor- und Frühgeschichte" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-936033-31-1

- ISBN 978-1-317-12415-3.

- ^ Stiftung, Gerda Henkel. "Die Hagia Sophia Justinians – Mathematischer Raum als Bühne des Kaisers". L.I.S.A. WISSENSCHAFTSPORTAL GERDA HENKEL STIFTUNG.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78925-030-5.

- JSTOR 1291426.

- JSTOR 44172340.

- ^ S2CID 201516637.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia Imperial Gate | Visit & Explore The Iconic Landmark". Hagia Sophia Tickets. 10 April 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- OCLC 1233690226.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISSN 0950-0618.

- ^ Kleiner and Mamiya. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, p. 331.

- ^ "pendentive (architecture) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- JSTOR 1566853.

- ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- ^ OCLC 15378795.

- ^ "Buttresses | Hagia Sophia Museum". ayasofyamuzesi.gov.tr. Directorate of Hagia Sophia Museum. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Mosque". Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Minarets | Hagia Sophia Museum". Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Ronchey (2010), p. 157

- ^ "Hagia Sophia: Facts, History & Architecture". Live Science. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Istanbul City Guide (English). ASBOOK. 2009.

- ^ "The Marble Door." The Marble Door |Hagia Sophia Museum, ayasofyamuzesi.gov.tr/en/door-marble-door.

- ^ ""The Nice Door." The nice door, Hagia Sophia Museum". Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ ""The Emperor Door." The Emperor Door, Hagia Sophia Museum". Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "'Imperial Gate' in Hagia Sophia Mosque vandalized". 21 April 2022. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Aya Sofya or Hagia Sophia Mosque-Church and Museum". Very Turkey. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ "The Architectural Review". Architectural Press Limited. 15 July 1905. Retrieved 15 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Discover the Beautiful Inside Hagia Sophia in Istanbul". istanbul-pulse.com. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- )

- ^ Gökovali, Şadan. Istanbul. Istanbul: Ticaret Matbaacilik T.A.Ş. p. 27.

- ^ "Hagia Sophia. Nova PBS program; originally aired 2/25/2015". YouTube. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b Hoffman (1999), p. 207

- ^ "Monuments éternels". Programmes ARTE. 21 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015.

- ^ "The Hagia Sophia". Mount Holyoke College. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ISSN 1876-6102.

- S2CID 129375039.

- ^ "The Hagia Sophia Church". Guideistanbul.net. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Imperial Door Mosaic". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-88-7470-229-9), pp. 357–71.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Southwestern Vestibule". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ JSTOR 24643764.

- JSTOR 1291228.

- S2CID 191481936.

- ISSN 0350-1361.

- ISSN 0141-6790.

- JSTOR 1291625.

- ISBN 978-0-226-57171-3.

- ^ JSTOR 1291518.

- ^ a b Galavaris, George P. (1964). "Observations on the date of the apse mosaic of the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople". Actes du XIIe Congrès International des Études Byzantines. 3: 107–110.

- ^ ISSN 2241-2190.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Apse Mosaic". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Lord Kinross. "Hagia Sophia: A History of Constantinople." Newsweek, 1972, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Emperor Alexander". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Empress Zoe". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Comnenus". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "Deesis". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Hagia Sophia. "North Tympanum". hagiasophia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Dome Angel Figures". Hagia Sophia Museum. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. (archived).

- ^ Almughrabi, Naser; Prijotomo, Josef; Faqih, Mohammad (6 June 2015). "SULEYMANIYE MOSQUE: SPACE CONSTRUCTION AND TECHNICAL CHALLENGES". International Journal of Education and Research. 3.

- ^ Piltz, Elisabeth (2014). "Hagia Sophia and Ottoman architecture". Byzantinoslavica - Revue internationale des Études Byzantines. 1–2: 293–309.

- JSTOR 3050788.

- ISBN 978-93-84422-65-3.

- ^ "Catedrala Ortodoxă: Strada Mitropoliei". sibiul.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ Ljubomir Milanović 2001: Materializing Authority: The Church of Saint Sava in Belgrade and its Architectural Significance. Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies, Volume 24, Numbers 1-2: 63-81 (PDF) Archived 29 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tanja Damnjanović 2005: "Fighting" the St. Sava: Public Reaction to the Competition for the Largest Cathedral in Belgrade. Centropa, 5 (2), 125–135.

- S2CID 159508818.

Sources

- Boyran, Ebru; Fleet, Kate (2010). A social History of Ottoman Istanbul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19955-1.

- Brubaker, Leslie; Haldon, John (2011). Byzantium in the Iconoclast era (ca 680–850). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43093-7.

- Cameron, Averil (2009). Οι Βυζαντινοί (in Greek). Athens: Psychogios. ISBN 978-960-453-529-3.

- Hagia Sophia. Hagia Sophia Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 23 September 2014.

- Heinle, Erwin; Schlaich, Jörg (1996), Kuppeln aller Zeiten, aller Kulturen, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-421-03062-6)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Hoffman, Volker (1999). Die Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (in German). Bern: Lang. ISBN 978-3-906762-81-4.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères. Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines.

- Mainstone, Rowland J. (1997). Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure, and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church (reprint ed.). W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8..

- Mamboury, Ernest (1953). The Tourists' Istanbul. Istanbul: Çituri Biraderler Basımevi.

- ISBN 978-0-913836-90-3.

- ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Necipoĝlu, Gulru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-244-7.

- Ronchey, Silvia; Braccini, Tommaso (2010). Il romanzo di Costantinopoli. Guida letteraria alla Roma d'Oriente (in Italian). Torino: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-18921-1.

- Runciman, Steven (1965). The Fall of Constantinople Archived 27 December 2022 at the ISBN 0-521-39832-0.

- Savignac, David (2020). "The Medieval Russian Account of the Fourth Crusade – A New Annotated Translation" – via Academia.edu.

- Stroth, Fabian (2021). Monogrammkapitelle. Die justinianische Bauskulptur Konstantinopels als Textträger (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert. ISBN 978-3-95490-272-9.

- Turner, J. (1996). ISBN 978-0-19-517068-9.

Further reading

See also the thematically organised full bibliography in Stroth 2021.[1]

- Balfour, John Patrick Douglas (1972). Hagia Sophia. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-88225-014-4.

- Cimok, Fatih (2004). Hagia Sophia. Milet Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-975-7199-61-8.

- Doumato, Lamia (1980). The Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia: Selected references. Vance Bibliographies. ASIN B0006E2O2M.

- Goriansky, Lev Vladimir (1933). Haghia Sophia: analysis of the architecture, art and spirit behind the shrine in Constantinople dedicated to Hagia Sophia. American School of Philosophy. ASIN B0008C47EA.

- Glinavos, I. (2021). "Hagia Sophia at ICSID? The Limits of Sovereign Discretion". European Yearbook of International Economic Law. Vol. 12. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 253–273. ISBN 978-3-031-05082-4.

- Harris, Jonathan, Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium. Hambledon/Continuum (2007). ISBN 978-1-84725-179-4

- Howland Swift, Emerson (1937). The bronze doors of the gate of the horologium at Hagia Sophia. University of Chicago. ASIN B000889GIG.

- Kahler, Heinz (1967). Haghia Sophia. Praeger. ASIN B0008C47EA.

- Kinross, Lord (1972). "Hagia Sophia, Wonders of Man". Newsweek. ASIN B000K5QN9W.

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugene; Anthony White (2007). Hagia Sophia. London: Scala Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85759-308-2.

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugene (2000). Saint Sophia at Constantinople: Singulariter in Mundo (Monograph (Frederic Lindley Morgan Chair of Architectural Design), No. 5.). William L. Bauhan. ISBN 978-0-87233-123-5.

- ISBN 978-0-300-05294-7.

- Mainstone, R.J. (1997). Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure, and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27945-8.

- Mainstone, Rowland J. (1988). Hagia Sophia. Architecture, structure and liturgy of Justinian's great church. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-34098-1.

- Mango, Cyril; Ahmed Ertuğ (1997). Hagia Sophia. A vision for empires. Istanbul.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mark, R.; Çakmaktitle, AS. (1992). Hagia Sophia from the Age of Justinian to the Present. Princeton Architectural. ISBN 978-1-878271-11-2.

- Nelson, Robert S. (2004). Hagia Sophia, 1850–1950: Holy Wisdom Modern Monument. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-57171-3.

- Özkul, T.A. (2007). Structural characteristics of Hagia Sophia: I-A finite element formulation for static analysis. Elsevier.

- Scharf, Joachim: Der Kaiser in Proskynese. Bemerkungen zur Deutung des Kaisermosaiks im Narthex der Hagia Sophia von Konstantinopel. In: Festschrift Percy Ernst Schramm zu seinem siebzigsten Geburtstag von Schülern und Freunden zugeeignet, Wiesbaden 1964, S. 27–35.

- Strube, Christine (1973). Polyeuktoskirche und Hagia Sophia. Umbildung und Auflösung antiker Formen, Entstehen des Kämpferkapitells. Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7696-0087-8.

- Swainson, Harold (2005). The Church of Sancta Sophia Constantinople: A Study of Byzantine Building. Boston, MA: Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4021-8345-4.

- ISBN 978-0-87099-179-0

- Xydis, Stephen G. (1947). "The Chancel Barrier, Solea, and Ambo of Hagia Sophia". The Art Bulletin. 29 (1): 1–24. JSTOR 3047098.

- Yucel, Erdem (2005). Hagia Sophia. Scala Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85759-250-4.

Articles

- Alchermes, Joseph D. (2005). "Art and Architecture in the Age of Justinian". In Maas, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P. pp. 343–75. ISBN 978-0-521-52071-3.

- Atchison, Bob (2020). "History of Hagia Sophia – the Church of Holy Wisdom". My World of Byzantium.

- Bordewich, Fergus M., "A Monumental Struggle to Preserve Hagia Sophia", Smithsonian magazine, December 2008

- Calian, Florian, The Hagia Sophia and Turkey's Neo-Ottomanism Archived 20 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Armenian Weekly.

- Osseman, Dick. "Aya Sofya Photo Gallery". Pbase.com.

- Ousterhout, Robert G. "Museum or Mosque? Istanbul's Hagia Sophia has been a monument to selective readings of history Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine." History Today (Sept 2020).

- Suchkov, Maxim, Why did Moscow call Ankara's Hagia Sophia decision "Turkey's internal affair"? Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Middle East Institute.

Mosaics

- Hagia Sophia, hagiasophia.com: Mosaics.

- MacDonald, William Lloyd (1951). The uncovering of Byzantine mosaics in Hagia Sophia. Archaeological Institute of America. ASIN B0007GZTKS.

- Mango, Cyril (1972). The mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: The church fathers in the north Tympanum. Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ASIN B0007CAVA0.

- Mango, Cyril (1968). The Apse mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: Report on work carried out in 1964. Johnson Reprints. ASIN B0007G5RBY.

- Mango, Cyril; Heinz Kahler (1967). Hagia Sophia: With a Chapter on the Mosaics. Praeger. ASIN B0000CO5IL.

- Teteriatnikov, Natalia B. (1998). Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The Fossati Restoration and the Work of the Byzantine Institute. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-264-0.

- Riccardi, Lorenzo (2012). Alcune riflessioni sul mosaico del vestibolo sud-ovest della Santa Sofia di Costantinopoli, in Vie per Bisanzio. VIII Congresso Nazionale dell'Associazione Italiana di Studi Bizantini (Venezia 25–28 novembre 2009), a cura di Antonio Rigo, Andrea Babuin e Michele Trizio. Bari. pp. 357–71. ISBN 978-88-7470-229-9.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Yücel, Erdem (1988). The mosaics of Hagia Sophia. Efe Turizm. ASIN B0007CBGYA.

External links

| External image | |

|---|---|

![Guillaume-Joseph Grelot [fr]'s engraving 1672, looking east and showing the apse mosaic](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Relation_nouvelle_d%27un_voyage_de_Constantinople_-_enrichie_de_plans_levez_par_l%27auteur_sur_les_lieux%2C_and_des_figures_de_tout_ce_qu%27il_y_a_de_plus_remarquable_dans_cette_ville_%281680%29_%2814773026492%29.jpg/92px-thumbnail.jpg)