History of Solidarity

This article is missing information about the history of Solidarity after 2020. (August 2023) |

The

In the 1990s, Solidarity's influence on politics of Poland waned. A political arm of the Solidarity movement, Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS), was founded in 1996 and would win the 1997 Polish parliamentary election, only to lose the subsequent 2001 Polish parliamentary election. Thereafter, Solidarity had little influence as a political party, though it became the largest trade union in Poland.

Pre-1980 roots (1970s)

In the 1970s and 1980s, the initial success of Solidarity in particular, and of dissident movements in general, was fed by a deepening crisis within Soviet-influenced societies. There was declining morale and worsening economic conditions (a

On October 16, 1978, the

Early strikes (1980)

Strikes did not occur merely due to problems that had emerged shortly before the labor unrest, but due to governmental and economic difficulties spanning more than a decade. In July 1980,

On August 14, the shipyard workers began their strike, organized by the

The Polish government enforced censorship, and official media said little about the "sporadic labor disturbances in Gdańsk"; as a further precaution, all phone connections between the coast and the rest of Poland were soon cut.

On August 16, delegations from other strike committees arrived at the shipyard.[1] Delegates (Bogdan Lis, Andrzej Gwiazda and others) together with shipyard strikers agreed to create an Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy, or MKS).[1] On August 17 a priest, Henryk Jankowski, performed a mass outside the shipyard's gate, at which 21 demands of the MKS were put forward. The list went beyond purely local matters, beginning with a demand for new, independent trade unions and going on to call for a relaxation of the censorship, a right to strike, new rights for the Church, the freeing of political prisoners, and improvements in the national health service.[1]

Next day, a delegation of KOR

On August 18, the

Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 21 a Governmental Commission (Komisja Rządowa) including

First Solidarity (1980–1981)

Encouraged by the success of the August strikes, on September 17 workers' representatives, including Lech Wałęsa, formed a nationwide labor union, Solidarity (Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy (NSZZ) "Solidarność").

Meanwhile, Solidarity had been transforming itself from a trade union into a social movement

Using strikes and other protest actions, Solidarity sought to force a change in government policies. In some cases, as in

Yet while Solidarity was ready to take up negotiations with the government,

Martial law (1981–1983)

After the Gdańsk Agreement, the Polish government was under increasing pressure from the Soviet Union to take action and strengthen its position. Stanisław Kania was viewed by Moscow as too independent, and on October 18, 1981, the Party Central Committee put him in the minority. Kania lost his post as First Secretary, and was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski, who adopted a strong-arm policy.[26]

On December 13, 1981, Jaruzelski began a crack-down on Solidarity, declaring

The range of support for the Solidarity was unique: no other movement in the world was supported by

Besides the Communist authorities, Solidarity was also opposed by some of the Polish (émigré) radical right, believing Solidarity or KOR to be disguised communist groups, dominated by Jewish Trotskyite Zionists.[34]

In July 1983, martial law was formally lifted, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid-to-late 1980s.[35]

Underground Solidarity (1982–1988)

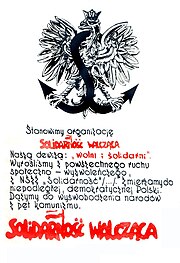

Almost immediately after the legal Solidarity leadership had been arrested, underground structures began to arise.[18] On April 12, 1982, Radio Solidarity began broadcasting.[20] On April 22, Zbigniew Bujak, Bogdan Lis, Władysław Frasyniuk and Władysław Hardek created an Interim Coordinating Commission (Tymczasowa Komisja Koordynacyjna) to serve as an underground leadership for Solidarity.[36] On May 6 another underground Solidarity organization, an NSSZ "S" Regional Coordinating Commission (Regionalna Komisja Koordynacyjna NSZZ "S"), was created by Bogdan Borusewicz, Aleksander Hall, Stanisław Jarosz, Bogdan Lis and Marian Świtek.[20] June 1982 saw the creation of a Fighting Solidarity (Solidarność Walcząca) organization.[36][37]

Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persevered as an exclusively underground organization.

On November 14, 1982,

On July 22, 1983, martial law was lifted, and amnesty was granted to many imprisoned Solidarity members, who were released.

On October 19, 1984 a popular pro-Solidarity priest, Jerzy Popiełuszko was killed.[43] As the facts emerged, thousands of people declared their solidarity with the deceased priest by attending his funeral, held on November 3, 1984. The government attempted to smooth over the situation by releasing thousands of political prisoners;[40] a year later, however, there followed a new wave of arrests.[18] Frasyniuk, Lis and Adam Michnik, members of the "S" underground, were brutally beaten and arrested on February 13, 1985, starved, tortured, interrogated, placed on a trial, and sentenced to several years' imprisonment for committing several acts of terror against Polish state and its people.[20][44]

Second Solidarity (1988–1989)

On March 11, 1985, power in the Soviet Union was assumed by

On September 11, 1986, 225 Polish political prisoners were released—the last of those connected with Solidarity, and arrested during the previous years.[40] Following amnesty on September 30, Wałęsa created the first public, legal Solidarity entity since the declaration of martial law—the Temporary Council of NSZZ Solidarność (Polish: Tymczasowa Rada NSZZ Solidarność)—with Bogdan Borusewicz, Zbigniew Bujak, Władysław Frasyniuk, Tadeusz Janusz Jedynak, Bogdan Lis, Janusz Pałubicki and Józef Pinior. Soon afterwards, the new Council was – exceptionally – admitted to both the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions and the World Confederation of Labour.[18] Many local Solidarity chapters now broke their cover throughout Poland, and on October 25, 1987, the National Executive Committee of NSZZ Solidarność (Polish: Krajowa Komisja Wykonawcza NSZZ Solidarność) was created. Nonetheless, Solidarity members and activists continued to be persecuted and discriminated, if less so than during the early 1980s.[20] In the late 1980s, a rift between Wałęsa's faction and a more radical Fighting Solidarity grew as the former wanted to negotiate with the government, while the latter planned for an anti-Communist revolution.[36][46][47]

By 1988, Poland's economy was in worse condition than it had been eight years earlier. International sanctions, combined with the government's unwillingness to introduce reforms, intensified the old problems.

In February 1988, the government hiked

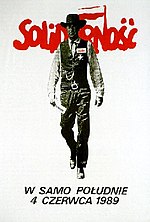

Solidarity Citizens' Committee election poster by Tomasz Sarnecki

On August 26,

On December 18, a hundred-member Citizens' Committee (Polish: Komitet Obywatelski) was formed within Solidarity. It comprised several sections, each responsible for presenting a specific aspect of opposition demands to the government. Wałęsa and the majority of Solidarity leaders supported negotiation, while a minority wanted an anti-Communist revolution. Under Wałęsa's leadership, Solidarity decided to pursue a peaceful solution, and the pro-violence faction never attained any substantial power, nor did it take any action.[24]

On January 27, 1989, in a meeting between Wałęsa and Kiszczak, a list was drawn up of members of the main negotiating teams. The conference that began on February 6 would be known as the Polish Round Table Talks.[51] The 56 participants included 20 from "S", 6 from OPZZ, 14 from the PZPR, 14 "independent authorities", and two priests. The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw from February 6 to April 4, 1989. The Communists, led by General Jaruzelski, hoped to co-opt prominent opposition leaders into the ruling group without making major changes in the structure of political power. Solidarity, while hopeful, did not anticipate major changes. In fact, the talks would radically alter the shape of the Polish government and society.[49][51]

On April 17, 1989, Solidarity was legalized, and its membership soon reached 1.5 million.

Pre-election

These elections, in which anti-Communist candidates won a striking victory, inaugurated a series of peaceful anti-Communist revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe[54][55] that eventually culminated in the Fall of Communism.[56][57]

The new Contract Sejm, named for the agreement that had been reached by the Communist party and the Solidarity movement during the Polish Round Table Talks, would be dominated by Solidarity. As agreed beforehand, Wojciech Jaruzelski was elected president;[49][52] however, the Communist candidate for Prime Minister, Czesław Kiszczak, who replaced Mieczysław Rakowski,[49] failed to gain enough support to form a government.[52][58]

On June 23, a Solidarity Citizens' Parliamentary Club (Obywatelski Klub Parliamentarny "Solidarność") was formed, led by

Party and trade union (1989–2020)

The fall of the Communist regime marked a new chapter in the history of Poland and in the history of Solidarity. Having defeated the Communist government, Solidarity found itself in a role it was much less prepared for — that of a political party — and soon began to lose popularity.[18][60] Conflicts among Solidarity factions intensified.[18][61] Wałęsa was elected Solidarity chairman, but support for him could be seen to be crumbling. One of his main opponents, Władysław Frasyniuk, withdrew from elections altogether. In September 1990, Wałęsa declared that Gazeta Wyborcza had no right to use the Solidarity logo. Later that month, Wałęsa announced his intent to run for president of Poland. In December 1990, he was elected president.[18] He resigned his Solidarity post and became the first president of Poland ever to be elected by popular vote.

In February 1991, Marian Krzaklewski was elected the leader of Solidarity.[18] President Wałęsa's vision and that of the new Solidarity leadership were diverging. Far from supporting Wałęsa, Solidarity was becoming increasingly critical of the government, and decided to create its own political party for action in the upcoming 1991 parliamentary elections.[62]

The 1991 elections were characterized by a large number of competing parties, many claiming the legacy of anti-Communism, and the Solidarity party garnered only 5% of the votes. On January 13, 1992, Solidarity declared its first strike against the democratically elected government: a one-hour strike against a proposal to raise energy prices. Another, two-hour strike took place on December 14. On May 19, 1993, Solidarity deputies proposed a

In the elections, Solidarity received only 4.9% of the votes, 0.1% less than the 5% required in order to enter parliament (Solidarity still had nine senators, two fewer than in the previous

Solidarity now joined forces with its erstwhile enemy, the

In June 1996,

In 2006, Solidarity had some 1.5 million members making it the largest trade union in Poland. Its

The

See also

- Organized labour portal

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Barker, Colin (October 17, 2005) [Autumn 2005]. "The Rise of Solidarnosc". International Socialism (108). Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ISBN 0-231-06608-2.

- ISBN 963-9241-39-3.

- ISBN 963-9241-39-3.

- ISBN 0-19-516664-7. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ISBN 0-06-073203-2.

- ^ a b c d e "The birth of Solidarity (1980)". BBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ISBN 0-271-02565-4.

- ISBN 0-275-95295-9.

- ^ Rosenberg, Steve (May 14, 2012). "The Cold War rival to Eurovision". BBC News. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ISBN 0-231-08093-X.

- ISBN 0-300-06921-9.

- ^ "Yalta 2.0". Warsaw Voice. August 31, 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ISBN 978-8361419402.

- ^ ISBN 0-231-12819-3.

- ISBN 0-521-83564-X.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-83564-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Solidarność NSZZ in WIEM Encyklopedia. Last accessed on October 10, 2006 (in Polish)

- ^ "Solidarity". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "KALENDARIUM NSZZ "SOLIDARNOŚĆ" 1980–1989" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. (185 KB). Last accessed on October 15, 2006 (in Polish)

- ^ Piotr Gliński, The Self-governing Republic in the Third Republic, "Polish Sociological Review", 2006, no.1

- ISBN 0-88738-049-2.

- ^ Jeff Goodwin, No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945–1991. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Chapter 1 and 8.

- ^ ISBN 1-55587-491-6. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ISBN 0-271-02528-X. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ a b c "Martial law (1981)". BBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ 25th anniversary of the strike in Piast coal mine Archived June 29, 2012, at archive.today

- ISBN 0-275-95295-9. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ISBN 0-300-09568-6.

- ^ ISBN 1-891620-82-7.

- ISBN 0-87113-633-3. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ ISBN 0-89526-514-1.

- ISBN 0-87722-900-7.

- ISBN 0-89526-514-1.

- ISBN 0-88132-136-2.

- ^ ISBN 0-8223-1548-3.

- ISBN 0-691-11627-X.

- ^ a b "Keeping the fire burning: the underground movement (1982–83)". BBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ISBN 0-8223-1548-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Negotiations and the big debate (1984–88)". BBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ "AROUND THE WORLD; Poland Says Mrs. Walesa Can Accept Nobel Prize". The New York Times. November 30, 1983. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ K. Gottesman (December 8, 2000). "Prawdziwe oświadczenie Lecha Wałęsy". Rzeczpospolita (no. 188). Archived from the original on December 13, 2003. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ISBN 0-19-516664-7. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ISBN 0-691-11627-X.

- ISBN 0-8166-3857-8.

- ISBN 1-56000-100-3, p. 221

- ISBN 0-521-83895-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Solidarity victorious (1989)". BBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ The Spring Will Be Ours

- ^ a b c d "Free elections (1989)". BBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ ISBN 0-8133-2835-7.

- ^ "Changes in the Polish media since 1989". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ISBN 0-415-93397-8. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ISBN 0-691-11627-X. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- ISBN 0-691-05028-7.

- ^ ISBN 0-7146-3463-8.

- ISBN 0-521-00070-X.

- ^ ISBN 0-472-11030-6. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ "Welcome to NSZZ Solidarnosc Web Site!". National Commission of Independent Self-Governing Trade Union. Archived from the original on October 25, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ "W Gdańsku otwarto Europejskie Centrum Solidarności" (in Polish). Onet.pl. August 31, 2014. Archived from the original on December 13, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ "From the Niagara falls to Rio de Janeiro's statue of Christ the Redeemer, the colours of Poland light up to mark 40 years since historic pro-democracy agreements". Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Mural w Berlinie, most nad Dunajem, iluminacja w Waszyngtonie na 40 lat Porozumień Sierpniowych". Retrieved September 1, 2020.

Further reading

- ISBN 0-396-08065-0.

- Pope John Paul II (May 19, 2003). "Sollicitudo Rei Socialis". Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- Kenney, Patrick (2006). The Burdens of Freedom. Zed Books Ltd. ISBN 1-84277-662-2.

- Matynia, Elzbieta (2009). Performative Democracy. Paradigm. ISBN 978-1594516566.

- Osa, Maryjane (2003). Solidarity and Contention: Networks of Polish Opposition. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3874-8.

- Ost, David (2005). The Defeat of Solidarity: Anger and Politics in Postcommunist Europe (ebook). Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4318-0.

- Paczkowski, Andrzej. Revolution and Counterrevolution in Poland, 1980-1989: Solidarity, Martial Law, and the End of Communism in Europe (Boydell & Brewer, 2015).

- Penn, Shana (2005). Solidarity's Secret: The Women Who Defeated Communism in Poland. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11385-2.

- Perdue, William D. (1995). Paradox of Change: The Rise and Fall of Solidarity in the New Poland. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-95295-9.

- Staniszkis, Jadwiga (1984). Poland's Self-Limiting Revolution. Princeton University Press.

- Szporer, Michael (2012). Solidarity: The Great Workers Strike of 1980. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739174883.

External links

- Interview with Henry Kissinger on US – Soviet Relations during Solidarity from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Presentation The Solidarity Phenomenon (in Polish, English, German, French, Spanish, and Russian)

- Solidarity official English homepage

- Solidarity 25th Anniversary Press Center

- International Conference 'From Solidarity to Freedom'

- Poland: Solidarity – The Trade Union That Changed The World

- Who Is Anna Walentynowicz?, a documentary film about Solidarity (in English and German)

- Advice for East German propagandists on how to deal with the Solidarity movement

- Solidarity, Freedom and Economical Crisis in Poland, 1980–81 Archived March 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Arch Puddington, How American Unions Helps Solidarity Win

- Michael Bernhard, The Polish Opposition and the Technology of Resistance

- The Independent Press in Poland, 1976–1990 – this site of the Library of Congress contains a list of Polish abbreviations and their English translations; many of which were used in this article

- (In Polish) Solidarity Center Foundation – Fundacja Centrum Solidarności

- Silver Coin Marks the 30th Anniversary of Poland's Solidarity Movement