Horseshoe arch

The horseshoe arch (

History

Origins and early uses

The origins of the horseshoe arch are controversial.

Another possible origin of the horseshoe arch motif is India, where rock-cut temples with horseshoe arches are attested at an early period, though these were sculpted into rock rather than constructed.[10][4] For example, horseshoe arch shapes are found in parts of the Ajanta Caves and Karla Caves dating from around the 1st century BCE to 1st century CE.[11]

Horseshoe arches made of baked brick have been found in the so-called Tomb of the Brick Arches in

Further evidence of their use is also found in

In early Islamic architecture, some horseshoe arches appeared in Umayyad architecture of the 7th to 8th centuries. They are found in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, though their horseshoe shape is not very pronounced.[23][24] They are also found in the Umayyad Palace at the Amman Citadel in present-day Jordan.[5]

According to Giovanni Teresio Rivoira, an archeologist writing in the early 20th century, the pointed variant of the horseshoe arch is of Islamic origin.

Development in the Iberian Peninsula and the Maghreb

It was in

In the northern Iberian Peninsula, where

Under the Almoravids (11th-12th centuries), the first pointed horseshoe arches began to appear in the region and then became more widespread during the Almohad period (12th-13th centuries). This pointed horseshoe arch is likely of North African origin.[28]: 234 Art historian Georges Marçais attributed it in particular to Ifriqiya (present-day Tunisia), where it was present in earlier Aghlabid and Fatimid architecture.[28]: 234

As Muslim rule retreated in Al-Andalus, the

-

Church of Santa Eulalia de Bóveda near Lugo, Spain (4th-5th century),[43] early Christian or Visigothic period

-

Church of San Juan de Baños in Spain (mid-7th century)[44]

-

Prayer hall of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, Spain (late 8th century)

-

Horseshoe arches in the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia (9th century)

-

Church of architecture

-

Caliphal-style arches of the Taifa palace (11th century) in the Alcazaba of Málaga, Spain

-

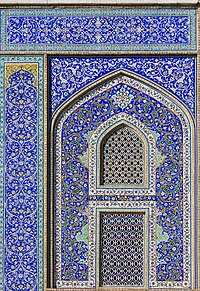

Pointed horseshoe arches in the Mosque of Tinmal, Morocco (12th century), typical of the Almohad period and afterwards

Use in other parts of the Islamic world

Horseshoe arches were also common in

though they were not a consistent feature in India.Some pointed arches with a slightly horseshoe shape appear in Ayyubid architecture in Syria.[49] It appears, exceptionally, in some instances of Mamluk architecture. For example, it appears in some details of the Sultan Qalawun Complex in Cairo, built in 1285.[50] Andalusi-style horseshoe arches are also found alongside the minaret of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, probably dating from 13th-century renovations ordered by Sultan Lajin to the older 9th-century mosque.[51]

Use in Moorish revival architecture

In addition to their use across the Islamic world, horseshoe arches became popular in Western countries in

Use in Art Nouveau

Exaggerated horseshoe arches were also popular in some forms of

Notes

- ^ The term "Mozarabic" is also applied to the culture of communities outside Al-Andalus, in the northern Christian territories, where Christians from al-Andalus immigrated and resettled, particularly in the 10th century. However, the term reboplación, among other alternatives, can be used to refer to this culture.[35]

References

- ISBN 978-90-04-16549-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ISBN 978-0-486-13211-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4744-5046-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-16549-6.

- ISBN 978-92-9063-144-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques. pp. 163–164.

- ISBN 0-415-21332-0, p. 24

- S2CID 194947480.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7486-0106-6.

- ISBN 978-0-87413-399-8.

- ISBN 978-1-134-25986-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-503-50947-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88402-310-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-11-033176-9.

- JSTOR 991243.

- ISBN 978-1-4744-1130-1.

- ISBN 978-1-137-02964-5.

- ISBN 978-0-88844-073-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- ^ "Hallan una estela discoidea con arcos de herradura en las murallas de León". www.soitu.es. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Umayyad Palace at Amman". Archnet. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ISBN 978-1-78738-305-0.

- ISBN 978-977-424-476-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8156-6044-6.

- ^ Swelim, Tarek (2015). Ibn Tulun: His Lost City and Great Mosque. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 65.

- ISBN 978-977-424-476-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- ^ a b "Arch". ArchNet — Digital Library — Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ^ "Qantara - Mosque of the Three Doors". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ISBN 978-0-271-00671-0.

- ISBN 3822876348.

- ^ ISBN 3822876348.

- ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ ISBN 9780195309911.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-9324-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-968027-6.

- ISBN 978-0-271-00671-0.

- ISBN 978-90-04-13789-9.

- ISBN 978-90-04-50259-8.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ Kaplan, Gregory B. (2012). "The Mozarabic Horseshoe Arches in the Church of San Román de Moroso (Cantabria, Spain)". Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture. 3 (3): 1–18.

- ISBN 0821224565.

- ISBN 978-3-902782-15-1.

- ^ "Dar Mustafa Pasha - Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ ISBN 9780195309911.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ISBN 978-90-04-09626-4.

- ^ "Jerusalem Synagogue". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-7582-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8232-5000-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78500-768-2.

- ISBN 978-2-39025-045-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4742-9856-8.

![Church of San Juan de Baños in Spain (mid-7th century)[44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8a/Ba%C3%B1os_de_Cerrato_01_bas%C3%ADlica_by-dpc.jpg/120px-Ba%C3%B1os_de_Cerrato_01_bas%C3%ADlica_by-dpc.jpg)

![Mudéjar architecture in the Church of San Roman in Toledo, Spain (12th or 13th century)[45]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Iglesia_de_San_Rom%C3%A1n_%28Toledo%29._Interior.jpg/120px-Iglesia_de_San_Rom%C3%A1n_%28Toledo%29._Interior.jpg)

![Pointed horseshoe arches in Dar Mustapha Pasha in Algiers, Algeria (1799)[46]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Dar_mostafa_bacha.jpg/120px-Dar_mostafa_bacha.jpg)