Political integration of India

Before

In July 1946,

Although this process successfully integrated the vast majority of princely states into India, it was not as successful for a few, notably the former princely states of Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur, where active secessionist and separatist insurgencies continued to exist due to various reasons.

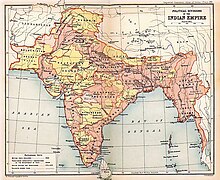

Princely states in India

The early history of British expansion in India was characterised by the co-existence of two approaches towards the existing princely states.

During the 20th century, the British made several attempts to integrate the princely states more closely with British India, in 1921 creating the

Neither paramountcy nor the subsidiary alliances could continue after Indian independence. The British took the view that because they had been established directly between the British crown and the princely states, they could not be transferred to the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan.[15] At the same time, the alliances imposed obligations on Britain that it was not prepared to continue to carry out, such as the obligation to maintain troops in India for the defence of the princely states. The British government therefore decided that paramountcy, together with all treaties between them and the princely states, would come to an end upon the British departure from India.[16]

Reasons for integration

The termination of paramountcy meant that all rights flowing from the states' relationship with the British crown would return to them, leaving them free to negotiate relationships with the new states of India and Pakistan "on a basis of complete freedom".

A few British leaders, particularly

Accepting integration

The princes' position

The rulers of the princely states were not uniformly enthusiastic about integrating their domains into independent India. The

A number of factors contributed to the collapse of this initial resistance and to nearly all non-Muslim majority princely states agreeing to accede to India. An important factor was the lack of unity among the princes. The smaller states did not trust the larger states to protect their interests, and many

Many princes were also pressured by popular sentiment favouring integration with India, which meant their plans for independence had little support from their subjects.[39] The Maharaja of Travancore, for example, definitively abandoned his plans for independence after the attempted assassination of his dewan, Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer.[40] In a few states, the chief ministers or dewans played a significant role in convincing the princes to accede to India.[41] The key factors that led the states to accept integration into India were, however, the efforts of Lord Mountbatten, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon. The latter two were respectively the political and administrative heads of the States Department, which was in charge of relations with the princely states.

Mountbatten's role

Mountbatten believed that securing the states' accession to India was crucial to reaching a negotiated settlement with the Congress for the transfer of power.

Mountbatten used his influence with the princes to push them towards accession. He declared that the British Government would not grant dominion status to any of the princely states, nor would it accept them into the

Mountbatten stressed that he would act as the trustee of the princes' commitment, as he would be serving as India's head of state well into 1948. He engaged in a personal dialogue with reluctant princes, such as the Nawab of Bhopal, who he asked through a confidential letter to sign the Instrument of Accession making Bhopal part of India, which Mountbatten would keep locked up in his safe. It would be handed to the States Department on 15 August only if the Nawab did not change his mind before then, which he was free to do. The Nawab agreed, and did not renege over the deal.[46]

At the time, several princes complained that they were being betrayed by Britain, who they regarded as an ally,[47] and Sir Conrad Corfield resigned his position as head of the Political Department in protest at Mountbatten's policies.[40] Mountbatten's policies were also criticised by the opposition Conservative Party.[48] Winston Churchill compared the language used by the Indian government with that used by Adolf Hitler before the invasion of Austria.[49] Modern historians such as E. W. R. Lumby and R. J. Moore, however, take the view that Mountbatten played a crucial role in ensuring that the princely states agreed to accede to India.[50]

Pressure and diplomacy

By far the most significant factor that led to the princes' decision to accede to India was the policy of the Congress and, in particular, of Patel and Menon. The Congress' stated position was that the princely states were not sovereign entities, and as such could not opt to be independent notwithstanding the end of paramountcy. The princely states must therefore accede to either India or Pakistan.[51] In July 1946, Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.[40] In January 1947, he said that independent India would not accept the divine right of kings,[52] and in May 1947, he declared that any princely state which refused to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as an enemy state.[40] Other Congress leaders, such as C. Rajagopalachari, argued that as paramountcy "came into being as a fact and not by agreement", it would necessarily pass to the government of independent India, as the successor of the British.[53]

Patel and Menon, who were charged with the actual job of negotiating with the princes, took a more conciliatory approach than Nehru.[54] The official policy statement of the Government of India made by Patel on 5 July 1947 made no threats. Instead, it emphasised the unity of India and the common interests of the princes and independent India, reassured them about the Congress' intentions, and invited them to join independent India "to make laws sitting together as friends than to make treaties as aliens".[55] He reiterated that the States Department would not attempt to establish a relationship of domination over the princely states. Unlike the Political Department of the British Government, it would not be an instrument of paramountcy, but a medium whereby business could be conducted between the states and India as equals.[56]

Instruments of accession

Patel and Menon backed up their diplomatic efforts by producing treaties that were designed to be attractive to rulers of princely states. Two key documents were produced. The first was the

The Instruments of Accession implemented a number of other safeguards. Clause 7 provided that the princes would not be bound to the

Accession process

The limited scope of the Instruments of Accession and the promise of a wide-ranging autonomy and the other guarantees they offered, gave sufficient comfort to many rulers, who saw this as the best deal they could strike given the lack of support from the British, and popular internal pressures.

Border states

The ruler of

In the northeast India, the border states of Manipur and Tripura acceded to India on 11 August and 13 August respectively.[68][69]

Junagadh

Although the states were in theory free to choose whether they wished to accede to India or Pakistan, Mountbatten had pointed out that "geographic compulsions" meant that most of them must choose India. In effect, he took the position that only the states that shared a border with Pakistan could choose to accede to it.[64]

The Nawab of Junagadh, a princely state located on the south-western end of Gujarat and having no common border with Pakistan, chose to accede to Pakistan ignoring Mountbatten's views, arguing that it could be reached from Pakistan by sea. The rulers of two states that were subject to the suzerainty of Junagadh—Mangrol and Babariawad—reacted to this by declaring their independence from Junagadh and acceding to India. In response, the Nawab of Junagadh militarily occupied the states. The rulers of neighbouring states reacted angrily, sending their troops to the Junagadh frontier and appealed to the Government of India for assistance. A group of Junagadhi people, led by Samaldas Gandhi, formed a government-in-exile, the Aarzi Hukumat ("provisional government").[70]

India believed that if Junagadh was permitted to go to Pakistan, the communal tension already simmering in Gujarat would worsen, and refused to accept the accession. The government pointed out that the state was 80% Hindu, and called for a referendum to decide the question of accession. Simultaneously, they cut off supplies of fuel and coal to Junagadh, severed air and postal links, sent troops to the frontier, and reoccupied the principalities of Mangrol and Babariawad that had acceded to India.[71] Pakistan agreed to discuss a plebiscite, subject to the withdrawal of Indian troops, a condition India rejected. On 26 October, the Nawab and his family fled to Pakistan following clashes with Indian troops. On 7 November, Junagadh's court, facing collapse, invited the Government of India to take over the State's administration. The Government of India agreed.[72] A plebiscite was conducted in February 1948, which went almost unanimously in favour of accession to India.[73]

Jammu and Kashmir

At the time of the transfer of power, the state of Jammu and Kashmir (widely called "Kashmir") was ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu, although the state itself had a Muslim majority. Hari Singh was equally hesitant about acceding to either India or Pakistan, as either would have provoked adverse reactions in parts of his kingdom.[74] He signed a Standstill Agreement with Pakistan and proposed one with India as well,[75] but announced that Kashmir intended to remain independent.[64] However, his rule was opposed by Sheikh Abdullah, the popular leader of Kashmir's largest political party, the National Conference, who demanded his abdication.[75]

Pakistan, attempting to force the issue of Kashmir's accession, cut off supplies and transport links. Its transport links with India were tenuous and flooded during the rainy season. Thus Kashmir's only links with the two dominions was by air. Rumours about atrocities against the Muslim population of

Indian troops secured

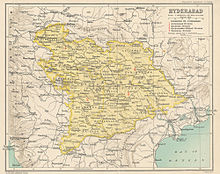

Hyderabad

Hyderabad was a landlocked state that stretched over 82,000 square miles (over 212,000 square kilometres) in southeastern India. While 87% of its 17 million people were Hindu, its ruler

The Nizam was prepared to enter into a limited treaty with India, which gave Hyderabad safeguards not provided for in the standard Instrument of Accession, such as a provision guaranteeing Hyderabad's neutrality in the event of a conflict between India and Pakistan. India rejected this proposal, arguing that other states would demand similar concessions. A temporary Standstill Agreement was signed as a stopgap measure, even though Hyderabad had not yet agreed to accede to India.[85] By December 1947, however, India was accusing Hyderabad of repeatedly violating the Agreement, while the Nizam alleged that India was blockading his state, a charge India denied.[86]

The Nizam was also beset by the

On 13 September 1948, the

Completing integration

The Instruments of Accession were limited, transferring control of only three matters to India, and would by themselves have produced a rather loose federation, with significant differences in administration and governance across the various states. Full political integration, in contrast, would require a process whereby the political actors in the various states were "persuaded to shift their loyalties, expectations, and political activities towards a new center", namely, the

Fast-track integration

The first step in this process carried out between 1947 and 1950, was to merge the smaller states that were not seen by the Government of India to be viable administrative units either into neighbouring provinces, or with other princely states to create a "princely union".[100] This policy was contentious since it involved the dissolution of the very states whose existence India had only recently guaranteed in the Instruments of Accession.[101][failed verification] Patel and Menon emphasised that without integration, the economies of states would collapse, and anarchy would arise if the princes were unable to provide democracy and govern properly. They pointed out that many of the smaller states were very small and lacked resources to sustain their economies and support their growing populations. Many also imposed tax rules and other restrictions impeding free trade, which had to be dismantled in a united India.[101][failed verification]

Given that the merger involved the breach of guarantees personally given by Mountbatten, initially, Patel and Nehru intended to wait until after his term as

The Merger Agreements required rulers to cede "full and exclusive jurisdiction and powers for and in relation to governance" of their state to the

A second kind of 'merger' agreement was demanded from larger states along sensitive border areas:

Four-step integration

Merger

The bulk of the larger states, and some groups of small states, were integrated through a different, four-step process. The first step in this process was to convince adjacent large states and a large number of adjacent small states to combine to form a "princely union" through the execution by their rulers of Covenants of Merger. Under the Covenants of Merger, all rulers lost their ruling powers, save one who became the

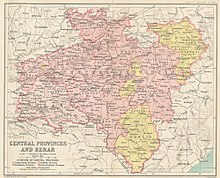

Through this process, Patel obtained the unification of 222 states in the

Democratisation

Merging the administrative machineries of each state and integrating them into one political and administrative entity was not easy, particularly as many of the merged states had a history of rivalry. In the former

The result of this process has been described as being, in effect, an assertion of paramountcy by the Government of India over the states in a more pervasive form.[116] While this contradicted the British statement that paramountcy would lapse on the transfer of power, the Congress position had always been that independent India would inherit the position of being the paramount power.[53]

Centralisation and constitutionalisation

Democratisation still left open one important distinction between the former princely states and the former British provinces, namely, that since the princely states had signed limited Instruments of Accession covering only three subjects, they were insulated from government policies in other areas. The Congress viewed this as hampering its ability to frame policies that brought about

Effective from 1950, the Constitution of India classified the constituent units of India into three classes—Part A, B, and C states. The former British provinces, together with the princely states that had been merged into them, were the Part A states. The princely unions, plus Mysore and Hyderabad, were the Part B states. The former Chief Commissioners' Provinces and other centrally administered areas, except the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, were the Part C states.[118] The only practical difference between the Part A states and the Part B states was that the constitutional heads of the Part B states were the Rajpramukhs appointed under the terms of the Covenants of Merger, rather than Governors appointed by the central government. In addition, Constitution gave the central government a significant range of powers over the former princely states, providing amongst other things that "their governance shall be under the general control of, and comply with such particular directions, if any, as may from time to time be given by, the President". Apart from that, the form of government in both was identical.[116]

Reorganisation

The distinction between Part A and Part B states was only intended to last for a brief, transitional period. In 1956, the

Post-integration issues

The princes

Although the progressive integration of the princely states into India was largely peaceful, not all princes were happy with the outcome. Many had expected the Instruments of Accession to be permanent, and were unhappy about losing the

Colonial enclaves

The integration of the princely states raised the question of the future of the remaining colonial

Portugal, in contrast, resisted diplomatic solutions. It viewed its continued possession of its enclaves in the Indian subcontinent as a matter of national pride[127] and, in 1951, it amended its constitution to convert its possessions in India into Portuguese provinces.[128] In July 1954, an uprising in Dadra and Nagar Haveli threw off Portuguese rule.[127] The Portuguese attempted to send forces from Daman to reoccupy the enclaves, but were prevented from doing so by Indian troops. Portugal initiated proceedings before the International Court of Justice to compel India to allow its troops access to the enclave, but the Court rejected its complaint in 1960, holding that India was within its rights in denying Portugal military access.[129] In 1961, the Constitution of India was amended to incorporate Dadra and Nagar Haveli into India as a Union Territory.[130]

Goa, Daman and Diu remained an outstanding issue. On 15 August 1955, five thousand non-violent demonstrators marched against the Portuguese at the border, and were met with gunfire, killing 22.

Sikkim

Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim were Himalayan states bordering India. Nepal had been recognised by the British by Nepal–Britain Treaty of 1923 as being de jure independent[124] and not a princely state. Bhutan had in the British period been considered a protectorate outside the international frontier of India.[124] The Government of India entered into a treaty with Bhutan in 1949 continuing this arrangement, and providing that Bhutan would abide by the advice of the Government of India in the conduct of its external affairs.[136] After 1947, India signed new treaties with Nepal and Bhutan.[137]

Historically, Sikkim was a British

In April 1973, anti-Chogyal agitation broke out and protestors demanded popular elections. The Sikkim police were unable to control the demonstrations, and Dorji asked India to exercise its responsibility for law and order and intervene. India facilitated negotiations between the Chogyal and Dorji, and produced an agreement, which envisaged the reduction of the Chogyal to the role of a

Secessionism and sub-nationalism

While the majority of princely states absorbed into India have been fully integrated, a few outstanding issues remain. The most prominent of these is in relation to Jammu and Kashmir, where a secessionist insurgency has been raging since 1989.[143]

Some academics suggest that the insurgency is at least partly a result of the manner in which it was integrated into India. Kashmir, uniquely amongst princely states, was not required to sign either a Merger Agreement or a revised Instrument of Accession giving India control over a larger number of issues than the three originally provided for. Instead, the power to make laws relating to Kashmir was granted to the Government of India by Article 5 of the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir and was, under Article 370 of the Constitution of India, somewhat more restricted than in relation to other states. Widmalm argues that during the 1980s, a number of Kashmiri youth began to feel that the Indian government was increasingly interfering in the politics of Jammu and Kashmir.[144] The elections of 1987 caused them to lose faith in the political process and begin the violent insurgency which is still ongoing.[144] Similarly, Ganguly suggests that the policies of the Indian government towards Kashmir meant that the state, unlike other parts of India, never developed the solid political institutions associated with a modern multi-ethnic democracy.[145] As a result, the growing dissatisfaction with the status quo felt by an increasingly politically aware youth was expressed through non-political channels[146] which Pakistan, seeking to weaken India's hold over Kashmir, transformed into an active insurgency.[147]

Separatist movements also exist in two other former princely states located in Northeast India— Tripura and

The integration of former princely states with other provinces to form new states has also given rise to some issues. The

Critical perspectives on the process of integration

The integration process repeatedly brought Indian and Pakistani leaders into conflict. During negotiations, Jinnah, representing the Muslim League, strongly supported the right of the princely states to remain independent, joining neither India nor Pakistan, an attitude which was diametrically opposed to the stance taken by Nehru and the Congress[151] and which was reflected in Pakistan's support of Hyderabad's bid to stay independent. Post-partition, the Government of Pakistan accused India of hypocrisy on the ground that there was little difference between the accession of the ruler of Junagadh to Pakistan—which India refused to recognise—and the accession of the Maharajah of Kashmir to India, and for several years refused to recognise the legality of India's incorporation of Junagadh, treating it as de jure Pakistani territory.[73]

Different theories have been proposed to explain the designs of Indian and Pakistani leaders in this period. Rajmohan Gandhi postulates that an ideal deal working in the mind of Patel was that if Muhammad Ali Jinnah let India have Junagadh and Hyderabad, Patel would not object to Kashmir acceding to Pakistan.[152] In his book Patel: A Life, Gandhi asserts that Jinnah sought to engage the questions of Junagadh and Hyderabad in the same battle. It is suggested that he wanted India to ask for a plebiscite in Junagadh and Hyderabad, knowing thus that the principle then would have to be applied to Kashmir, where the Muslim-majority would, he believed, vote for Pakistan. A speech by Patel at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter's take-over, where he said that "we would agree to Kashmir if they agreed to Hyderabad", suggests that he may have been amenable to this idea.[153] Although Patel's opinions were not India's policy, nor were they shared by Nehru, both leaders were angered at Jinnah's courting the princes of Jodhpur, Bhopal and Indore, leading them to take a harder stance on a possible deal with Pakistan.[154]

Modern historians have also re-examined the role of the States Department and Lord Mountbatten during the accession process. Ian Copland argues that the Congress leaders did not intend the settlement contained in the Instruments of Accession to be permanent even when they were signed, and at all times privately contemplated a complete integration of the sort that ensued between 1948 and 1950.[114] He points out that the mergers and cession of powers to the Government of India between 1948 and 1950 contravened the terms of the Instruments of Accession, and were incompatible with the express assurances of internal autonomy and preservation of the princely states which Mountbatten had given the princes.[155] Menon in his memoirs stated that the changes to the initial terms of accession were in every instance freely consented to by the princes with no element of coercion. Copland disagrees, on the basis that foreign diplomats at the time believed that the princes had been given no choice but to sign, and that a few princes expressed their unhappiness with the arrangements.[156] He also criticises Mountbatten's role, saying that while he stayed within the letter of the law, he was at least under a moral obligation to do something for the princes when it became apparent that the Government of India was going to alter the terms on which accession took place, and that he should never have lent his support to the bargain given that it could not be guaranteed after independence.[157] Both Copland and Ramusack argue that, in the ultimate analysis, one of the reasons why the princes consented to the demise of their states was that they felt abandoned by the British, and saw themselves as having little other option.[158] Older historians such as Lumby, in contrast, take the view that the princely states could not have survived as independent entities after the transfer of power, and that their demise was inevitable. They therefore view successful integration of all princely states into India as a triumph for the Government of India and Lord Mountbatten, and as a tribute to the sagacity of the majority of princes, who jointly achieved in a few months what the Empire had attempted, unsuccessfully, to do for over a century—unite all of India under one rule.[159]

See also

- All Indian States People's Conference

- List of princely states of British India

Notes

- ISBN 978-0-670-09129-4. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- George Allen & Unwin. p. 228

- ^ Tiwari, Aaditya (30 October 2017). "Sardar Patel – Man who United India". pib.gov.in. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "How Vallabhbhai Patel, V P Menon and Mountbatten unified India". 31 October 2017. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Ramusack 2004, pp. 57–59

- ^ Ramusack 2004, pp. 55–56; Fisher 1984, pp. 393–428

- ^ Copland 1997, pp. 15–16

- ^ Lee-Warner 1910, pp. 48–51

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 202–204

- ^ Ashton 1982, pp. 29–57

- ^ McLeod 1999, p. 66

- ^ Keith 1969, pp. 506–514

- ^ Ramusack 1978, pp. chs 1–3

- ^ Copland 1993, pp. 387–389

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 218–219

- ^ Copland 1993, pp. 387–388

- ^ Wood et al. 1985, pp. 690–691

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 214–215

- ^ Menon 1956, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Rangaswami 1981, pp. 235–246

- ^ Phadnis 1969, pp. 360–374

- ^ Ramusack 1988, pp. 378–381

- ^ Copland 1987, pp. 127–129

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 224–225

- ^ Moore 1983, pp. 290–314

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 204

- ^ Copland 1993, pp. 393–394

- ^ Copland 1997, p. 237

- ^ a b Ramusack 2004, p. 273

- ^ Copland 1993, p. 393; Lumby 1954, p. 232

- ^ Morris-Jones 1983, pp. 624–625

- ^ Spate 1948, pp. 15–16; Wainwright 1994, pp. 99–104

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 215, 232

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 226–227

- ^ Ramusack 2004, p. 272

- ^ Copland 1997, pp. 233–240

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 229

- ^ Copland 1997, p. 244

- ^ Copland 1997, p. 232

- ^ a b c d e Copland 1997, p. 258

- ^ Phadnis 1968, pp. 170–171, 192–195

- ^ Copland 1997, pp. 253–254

- ^ Copland 1993, pp. 391–392

- ^ Copland 1997, p. 255

- ^ Gandhi 1991, pp. 411–412

- ^ Gandhi 1991, pp. 413–414

- ^ Copland 1993, p. 385

- ^ Copland 1997, p. 252

- ^ Eagleton 1950, p. 283

- ^ Moore 1983, p. 347; Lumby 1954, p. 236

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 232

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 228

- ^ a b Lumby 1954, pp. 218–219, 233

- ^ Brown 1984, p. 667

- ^ Menon 1956, pp. 99–100

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 234

- ^ Menon 1956, pp. 109–110

- ^ Copland 1993, p. 399

- ^ Copland 1997, p. 256

- ^ Copland 1993, p. 396

- ^ Copland 1993, p. 396; Menon 1956, p. 120

- ^ Menon 1956, p. 114

- ^ Ramusack 2004, p. 274

- ^ a b c Copland 1997, p. 260

- ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Mosley 1961, p. 177

- ^ Menon 1956, pp. 116–117

- ISBN 978-81-241-0902-1

- ISBN 978-81-8370-110-5: "Maharani Kanchan Prabha Devi as President of the 'Council of Regency' signed the 'Instrument of Accession' on 13 August 1947."

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 237–238

- ^ Lumby 1954, p. 238

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 238–239

- ^ a b Furber 1951, p. 359

- ^ Menon 1956, pp. 394–395

- ^ a b Lumby 1954, p. 245

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 245–247

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 247–248

- ^ Potter 1950, p. 361

- ^ Potter 1950, pp. 361–362

- ^ Security Council 1957, p. 359

- ^ "Causes of the 1962 Sino-Indian War: A Systems Level Approach". Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies. 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Talbot 1949, pp. 323–324

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 240

- ^ Talbot 1949, pp. 324–325

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 243–244

- ^ Talbot 1949, pp. 325–326

- ^ Puchalapalli 1973, pp. 18–42

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 224

- ^ a b Talbot 1949, p. 325

- ^ Eagleton 1950, pp. 277–280

- ^ Gandhi 1991, p. 483

- ^ Thomson 2013

- ^ Noorani 2001

- ^ Talbot 1949, pp. 326–327

- ^ Eagleton 1950, p. 280; Talbot 1949, pp. 326–327

- ^ Wood 1984, p. 68

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 363

- ^ Wood 1984, p. 72

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 352

- ^ a b Copland 1997, p. 262

- ^ a b Menon 1956, pp. 193–194

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 354–355

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 355–356

- ^ a b Furber 1951, pp. 366–367

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 354, 356

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 358–359

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 358

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 359–360

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 36o

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 361

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 362–363

- ^ Muzaffar, H. Syed (20 February 2022). History of Indian Nation : Post-Independence India. K.K. Publications.

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 367–368

- ^ a b c d e Copland 1997, p. 264

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 357–358, 360

- ^ a b Furber 1951, pp. 369–370

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 357

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 352–354

- ^ a b c d Copland 1997, p. 266

- ^ Gledhill 1957, p. 270

- ^ Roberts 1972, pp. 79–110

- ^ Furber 1951, pp. 354, 371

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 371

- ^ a b c Furber 1951, p. 369

- ^ Fifield 1950, p. 64

- ^ Vincent 1990, pp. 153–155

- ^ a b Karan 1960, p. 188

- ^ a b Fisher 1962, p. 4

- ^ Karan 1960, pp. 188–190

- ^ Fisher 1962, p. 8

- ^ a b Fisher 1962, p. 6

- ^ Fisher 1962, pp. 8–10

- ^ Fisher 1962, p. 10

- ^ Wright 1962, p. 619

- ^ "Goa, Daman and Diu Reorganisation Act, 1987". 23 May 1987.

- ^ Fifield 1952, pp. 450

- ^ "The India-China Competition in the Himalayas: Nepal and Bhutan". ISPI. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Furber 1951, p. 369; Note 1975, p. 884

- ^ Gupta 1975, pp. 789–790

- ^ Gupta 1975, pp. 790–793

- ^ Gupta 1975, pp. 793–795

- ^ Note 1975, p. 884

- ^ Zutshi 2017, p. 123

- ^ a b Widmalm 1997, pp. 1019–1023

- ^ Ganguly 1996, pp. 99–101

- ^ Ganguly 1996, pp. 91–105

- ^ Ganguly 1996, p. 103

- ^ See e.g. Hardgrave 1983, pp. 1173–1177; Guha 1984, pp. 42–65; Singh 1987, pp. 263–264

- ^ Gray 1971, pp. 463–474

- ^ Mitra 2006, p. 133

- ^ Menon 1956, pp. 86–87

- ^ Gandhi 1991, pp. 430–438

- ^ Gandhi 1991, p. 438

- ^ Gandhi 1991, pp. 407–408

- ^ Copland 1993, pp. 399–401

- ^ Copland 1997, pp. 266, 271–272

- ^ Copland 1993, pp. 398–401

- ^ Ramusack 2004, p. 274; Copland 1997, pp. 355–356

- ^ Lumby 1954, pp. 218; Furber 1951, p. 359

Sources

- Ashton, S.R. (1982), British Policy towards the Indian States, 1905–1938, London Studies on South Asia no. 2, London: Curzon Press, ISBN 0-7007-0146-X

- Brown, Judith M. (1984), "The Mountbatten Viceroyalty. Announcement and Reception of the 3 June Plan, 31 May-7 July 1947", The English Historical Review, 99 (392): 667–668,

- Copland, Ian (1987), "Congress Paternalism: The "High Command" and the Struggle for Freedom in Princely India"", in Masselos, Jim (ed.), Struggling and Ruling: The Indian National Congress 1885–1985, New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, pp. 121–140, ISBN 81-207-0691-9

- Copland, Ian (1993), "Lord Mountbatten and the Integration of the Indian States: A Reappraisal", The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 21 (2): 385–408,

- Copland, Ian (1997), The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-57179-0

- Eagleton, Clyde (1950), "The Case of Hyderabad Before the Security Council", The American Journal of International Law, 44 (2), American Society of International Law: 277–302, JSTOR 2193757

- Fifield, Russell H. (1950), "The Future of French India", Far Eastern Review, 19 (6): 62–64, JSTOR 3024284

- Fifield, Russell H. (1952), "New States in the Indian Realm", The American Journal of International Law, 46 (3), American Society of International Law: 450–463, S2CID 147372554

- Fisher, Margaret W. (1962), "Goa in Wider Perspective", Asian Survey, 2 (2): 3–10, JSTOR 3023422

- Fisher, Michael H. (1984), "Indirect Rule in the British Empire: The Foundations of the Residency System in India (1764–1858)", Modern Asian Studies, 18 (3): 393–428, S2CID 145053107

- JSTOR 2753451

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (1991), Patel: A Life, Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House

- Ganguly, Sumit (1996), "Explaining the Kashmir Insurgency: Political Mobilization and Institutional Decay", International Security, 21 (2), The MIT Press: 76–107, JSTOR 2539071

- Gledhill, Alan (1957), "Constitutional and Legislative Development in the Indian Republic", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 20 (1–3): 267–278, S2CID 154488404

- Gray, Hugh (1971), "The Demand for a Separate Telangana State in India" (PDF), Asian Survey, 11 (5): 463–474, JSTOR 2642982

- Guha, Amalendu (1984), "Nationalism: Pan-Indian and Regional in a Historical Perspective", Social Scientist, 12 (2): 42–65, JSTOR 3517093

- Gupta, Ranjan (1975), "Sikkim: The Merger with India", Asian Survey, 15 (9): 786–798, JSTOR 2643174

- Hardgrave, Robert L. (1983), "The Northeast, the Punjab, and the Regionalization of Indian Politics", Asian Survey, 23 (11): 1171–1181, S2CID 153480249

- Karan, Pradyumna P. (1960), "A Free Access to Colonial Enclaves", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 50 (2): 188–190,

- Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1969), A Constitutional History of India, 1600–1935 (2nd ed.), London: Methuen

- Lee-Warner, Sir William (1910), "The Native States of India", The Geographical Journal, 36 (6) (2nd ed.), London: Macmillan: 721, JSTOR 1776856

- Lumby, E.W.R. (1954), The Transfer of Power in India, 1945–1947, London: George Allen and Unwin

- McLeod, John (1999), Sovereignty, Power, Control: Politics in the State of Western India, 1916–1947, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11343-6

- Menon, V. P. (1956), The Story of the Integration of the Indian States, New York: Macmillan – via archive.org

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of India (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521682251

- Mitra, Subrata Kumar (2006), The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-34861-7

- Moore, R.J. (1983), Escape from Empire: The Attlee Government and the Indian Problem, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-822688-8

- Morris-Jones, W.H. (1983), "Thirty-Six Years Later: The Mixed Legacies of Mountbatten's Transfer of Power", International Affairs, 59 (4): 621–628, JSTOR 2619473

- Mosley, Leonard (1961), The last days of the British Raj, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Noorani, A. G. (3–16 March 2001), "Of a massacre untold", Frontline, 18 (5), retrieved 8 September 2014

- Note (1975), "Current Legal Developments: Sikkim, Constituent Unit of India", International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 24 (4): 884,

- Phadnis, Urmila (1968), Towards the Integration of the Indian States, 1919–1947, London: Asia Publishing House

- Phadnis, Urmila (1969), "Gandhi and Indian States: A Probe in Strategy", in Biswas, S.C. (ed.), Gandhi: Theory and Practice, Social Impact and Contemporary Relevance, Transactions of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study Vol. 2, Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, pp. 360–374

- Potter, Pitman B. (1950), "The Principal Legal and Political Problems Involved in the Kashmir Case", The American Journal of International Law, 44 (2), American Society of International Law: 361–363, S2CID 146848599

- JSTOR 3516214, archived from the originalon 3 February 2014

- Ramusack, Barbara N. (1978), The Princes of India in the Twilight of Empire: Dissolution of a patron-client system, 1914–1939, Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, ISBN 0-8142-0272-1

- Ramusack, Barbara N. (1988), "Congress and the People's Movement in Princely India: Ambivalence in Strategy and Organisation", in Sisson, Richard; ISBN 0-520-06041-5

- Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004), The Indian Princes and Their States, ISBN 0-521-26727-7

- Rangaswami, Vanaja (1981), The Story of Integration: A New Interpretation in the Context of the Democratic Movements in the Princely States of Mysore, Travancore and Cochin 1900–1947, New Delhi: Manohar

- Roberts, Neal A. (1972), "The Supreme Court in a Developing Society: Progressive or Reactionary Force? A Study of the Privy Purse Case in India", The American Journal of Comparative Law, 20 (1), American Society of Comparative Law: 79–110, JSTOR 839489

- Security Council (1957), "Security Council: India-Pakistan Question", International Organization, 11 (2): 368–372, S2CID 249408902

- Singh, Buta. "Role of Sardar Patel in the Integration of Indian States." Calcutta Historical Journal (July-Dec 2008) 28#2 pp 65–78.

- Singh, B.P. (1987), "North-East India: Demography, Culture and Identity Crisis", Modern Asian Studies, 21 (2): 257–282, S2CID 145737466

- Spate, O.H.K. (1948), "The Partition of India and the Prospects of Pakistan", Geographical Review, 38 (1), American Geographical Society: 5–29, JSTOR 210736

- Talbot, Phillips (1949), "Kashmir and Hyderabad", World Politics, 1 (3), Cambridge University Press: 321–332, S2CID 154496730

- Thomson, Mike (24 September 2013), Hyderabad 1948: India's hidden massacre, BBC, retrieved 24 September 2013

- Vincent, Rose (1990), The French in India: From Diamond Traders to Sanskrit Scholars, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, translated by Latika Padgaonkar

- Wainwright, A. M. (1994), Inheritance of Empire: Britain, India and the Balance of Power in Asia, 1938–55, Westport: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-94733-5

- Widmalm, Sten (1997), "The Rise and Fall of Democracy in Jammu and Kashmir", Asian Survey, 37 (11): 1005–1030, JSTOR 2645738

- Wright, Quincy (1962), "The Goa Incident", The American Journal of International Law, 56 (3), American Society of International Law: 617–632, S2CID 147417854

- Wood, John (1984), "British versus Princely Legacies and the Political Integration of Gujarat", The Journal of Asian Studies, 44 (1): 65–99, S2CID 154751565

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2017). "Seasons of Discontent and Revolt in Kashmir". Current History. 116 (789): 123–129. JSTOR 48614247.

- Wood, John; JSTOR 2758474