Timeline of zoology

Appearance

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

This is a chronologically organized listing of notable zoological events and discoveries.

Ancient World

- 28000 BC. Cave paintings (e.g. Chauvet Cave) in Southern France and northern Spain depict animals in a stylized fashion. These European cave paintings depict Mammoths (the same species is later seen thawed ice in Siberia).

- 12000-8000 BC. antelopes, rhinoceros and catfish.

- 10000 BC. Humans (Homo sapiens) domesticated dogs, pigs, sheep, goats, fowl, and other animals in Europe, northern Africa and the Near East.[1]

- 6500 BC. The aurochs, ancestors of domestic cattle, were domesticated in the next two centuries if not earlier (Obre I, Yugoslavia). This was the last major animal to be tamed as a source of milk, meat, power, and leather in the Old World.

- 3500 BC. Sumerian animal-drawn wheeled vehicles and plows were developed in Mesopotamia, the region called the "Fertile Crescent". Irrigation was probably done using animal power. Since Sumeria had no natural defenses, armies with mounted cavalry and chariots became important which increased the importance of equines.

- 2000 BC. Domestication of the silkworm in China.

- 1100 BC. Won Chang (China), first of the from many parts of the world. The emperor also enjoyed sporting events with the use of animals.

- 850 BC. Homer (Greek) wrote the epics Iliad and Odyssey, both of them containing some correct observations on bees and fly maggots, while using animals as monsters and metaphors (gross soldiers turned into pigs by the witch Circe) and Both epics refer to mules.

- 610 BC. Anaximander (Greek, 610 BC–545 BC) was a student of Thales of Miletus. He was taught that the first life was formed by spontaneous generation in the mud. Later animals came into being by transmutations, left the water, and reached dry land. Man was derived from lower animals, probably aquatic. His writings, especially his poem On Nature, were read and cited by Aristotle and other later philosophers, but are lost now.

- 563? BC. Buddha (Indian, 563?–483 BC) had gentle ideas on the treatment of animals. He said that animals are held to have intrinsic worth, not just the values they derive from their usefulness to man.

- 500 BC. Empedocles of Agrigentum (Greek, 504–433 BC) reportedly rid a town of malaria by draining nearby swamps. He proposed the theory of the four humors and a natural origin of living things.

- 500 BC. Xenophanes (Greek, 576–460 BC), a disciple of Pythagoras (570–497 BC), first recognized fossils as animal remains and inferred that their presence on mountains indicated the latter had once been beneath the sea. "If horses or oxen had hands and could draw or make statues, horses would represent the forms of gods as horses, oxen as oxen." Galen (130–216 AD) revived interest in fossils that had been rejected by Aristotle, and the speculations of Xenophanes were again viewed with favor.

- 470 BC. Democritus of Abdera (Greek, 470–370 BC) made dissections of many animals and humans. He was the first Greek philosopher-scientist to propose a classification of animals, dividing them into blooded animals (Vertebrata) and bloodless animals (Evertebrata). He also held that lower animals had perfected organs and that the brain was the seat of thought.

- 460 BC. Hippocrates (Greek, 460–370 BC), the "Father of Medicine", used animal dissections to advance human anatomy.

- 440 BC. Herodotus of Halikarnassos (Greek, 484–425 BC) treated exotic fauna in his Historia, but his accounts are often based on tall tales. He explored the Nile, but much of ancient Egyptian civilization had already lost to living memory by his time.

- 427 BC. Plato (Greek, 427–347 BC) held that animals existed to serve man, but they should not be mistreated because this would lead people to mistreat others. Others who echoed this opinion are St. Thomas Aquinas, Immanuel Kant, and Albert Schweitzer.

- 384 BC. Aristotle's (Greek, 384–322 BC) books Historia Animalium (9 books), De Partibus Animalium, and De Generatione Animalium set the zoological stage for centuries. He emphasized the value of direct observation, recognized law and order in biological phenomena, and derived conclusions inductively from observations. He believed that there was a natural process of animals that ran from simple to complex. He made advances in marine biology, basing his writings on keen observation and rational interpretation as well as conversations with local Lesbos fishermen for two years, beginning in 344 BC. His account of male protection of eggs by the barking catfish was scorned for centuries until Louis Agassiz confirmed Aristotle's description.

- 323 BC. Alexander the Great (Macedonian, 356–323 BC) collected animals when he was not busy conquering the known world. He is credited with the introduction of the peacock into Europe.

- 70 BC. Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil) (70–19 BC) was a famous Roman poet. His poems Bucolics (42–37 BC) and Georgics (37–30 BC) hold much information on animal husbandry and farm life. His Aeneid (published posthumously) has many references to the zoology of his time.

- 36 BC. Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) wrote De Re Rustica, a treatise that includes apiculture. He also treated the problem of sterility in the mule and recorded a rare instance in which a fertilemule was bred.

- 50. Lucius Annaeus Seneca (Roman, 4 BC–65 AD), tutor to Roman emperor Nero, maintained that animals have no reason, just instinct, a "stoic" position.

Peacock endpapers from the Vienna Dioscurides

- 77. Pliny the Elder (Roman, 23–79) wrote his Historia Naturalis in 37 volumes. This work is a catch-all of zoological folklore, superstitions, and some good observations.

- 79. Pliny the Younger (Roman, 62–113), nephew of Pliny the Elder, inherited his uncle's notes and wrote on beekeeping.

- 100. Plutarch (Roman, 46–120) stated that animals' behavior is motivated by reason and understanding.

- 131. Galen of Pergamum (Greek, 130–216), physician to Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, wrote on human anatomy from dissections of animals. His texts were used for hundreds of years, gaining the reputation of infallibility.

- 200 c. Various compilers in post-classical and medieval times added to the Physiologus (or, more popularly, the Bestiary), the major book on animals for hundreds of years. Animals were believed to exist to serve man, if not as food or slaves then as moral examples.

- Early third century. Composition of De Natura Animalium by Claudius Aelianus (Roman, 175–235.)

Middle Ages

- 600. Isidorus Hispalensis (Spanish bishop of Seville) (560–636) wrote Origines sive Etymologiae, an encyclopedic compendium of ancient knowledge including information on animals that served until the rediscovery of Aristotle and Pliny. Full of errors, it nevertheless was influential for hundreds of years. He also wrote De Natura Rerum.

- 781. Al-Jahiz (Afro-Arab, 781–868/869), a scholar at Basra, wrote on the influence of environment on animals.

- 901. Horses came into wider use in those parts of Europe where the three-field system produces grain surpluses for feed, but hay-fed oxen were more economical, if less efficient, in terms of time and labor and remained almost the sole source of animal power in southern Europe, where most farmers continued to use the two-field system.

- 1225-1244. Thomas of Cantimpré‚ (Fleming, 1204?–1275?) wrote Liber de Natura Rerum, a major 13th-century encyclopedia.

- 1244–1248. Frederick II von Hohenstaufen (Holy Roman Emperor) (1194–1250) wrote De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (The Art of Hunting with Birds) as a practical guide to ornithology.

Manesse Codex, Zürich

- 1244. Vincentius Bellovacensis (Vincent of Beauvais) (?–1264) wrote Speculum Quadruplex Naturale, Doctrinale, Morale, Historiale (1244–1254), a major encyclopedia of the 13th century. This work comprises three huge volumes, of 80 books and 9,885 chapters.

- 1254–1323. Marco Polo (Italian, 1254–1323) provided information on Asiatic fauna, revealing new animals to Europeans. "Unicorns" (which may actually have been rhinos) were reported from southern China, but fantastic animals were otherwise not included.

- 1255–1270. Albertus Magnus of Cologne (Bavarian, 1206?–1280) (Albert von Bollstaedt or St. Albert) wrote De Animalibus. He promoted Aristotle but also included new material on the perfection and intelligence of animals, especially bees.

- 1304–1309. Apiculturewas discussed at length.

- 1492. Christopher Columbus (Italian) arrives in the New World. New animals soon begin to overload European zoology. Columbus is said to have introduced cattle, horses, and eight pigs from the Canary Islands to Hispaniola in 1493, giving rise to virtual devastation of that and other islands. Pigs were often set ashore by sailors to provide food on the ship's later return. Feral populations of hogs were often dangerous to humans.

- 1519–1520. , and other animals.

- 1523. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés(Spanish, 1478–1557), appointed official historiographer of the Indies in 1523, wrote Sumario de la Natural Historia delas Indias (Toledo, 1527). He was the first to describe many New World animals, such as the tapir, opossum, manatee, iguana, armadillo, anteaters, sloth, pelican, and hummingbirds.

Modern World

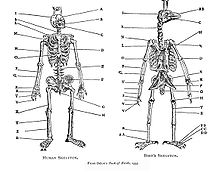

- 1551–1555. Pierre Belon (French, 1517–1564) wrote L'Histoire Naturelle des Estranges Poissons Marins (1551) and La Nature et Diversité des Poissons (1555). This latter work included 110 animal species and offered many new observations and corrections to Herodotus. L'Histoire de la nature des oyseaux avec leurs descriptions et naïfs portraicts (1555) was his picture book, with improved animal classification and accurate anatomical drawings. In this he published a man's and a bird's skeleton side by side to show the resemblance. He discovered an armadillo shell in a market in Syria, showing how Muslims were distributing the finds from the New World.

- 1551. Conrad Gessner (Swiss, 1516–1565) wrote Historia animalium (Tiguri, 4 vols., 1551–1558, last volume published in 1587) and gained renown. This work, although uncritically compiled in places, was consulted for over 200 years. He also wrote Icones animalum (1553) and Thierbuch (1563).

- 1552 Edward Wotton (English, 1492–1555) published De Differentiis Animalium, a work that influenced Gessner.

- 1554–1555. Guillaume Rondelet (French, 1507–1566) wrote Libri de piscibus marinis (1554) and Universe aquatilium historia (1555). He gathered vernacular names in hope of being able to identify the animal in question. He did go to print with discoveries that disagreed with Aristotle.

- 1578. Jean de Lery (French, 1534–1611) was a member of the French colony at Rio de Janeiro. He published Voyage en Amerique avec la description des animaux et plantes de ce pays (1578) with observations on the local fauna.

- 1585. (Limulus).

- 1589. José de Acosta (Spanish, 1539–1600) wrote De Natura Novi Orbis Libri duo (1589) and Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias (1590), describing many animals from the New World previously unknown to Europeans.

17th Century

- 1600. In Italy a spider scare lead to hysteria and the tarantella dance by which the body cures itself through physical exertions.

- 1602. Ulisse Aldrovandi (Italian, 1522–1605) wrote De Animalibus Insectis. This and his other works include many scientific inaccuracies, but he used wing and leg morphology to construct his classification of insects. He is more highly regarded for his ornithological contributions.

- 1604–1614. Francisco Hernández de Toledo (Spanish) was sent to study Mexican biota in 1593–1600, by Philip II of Spain. His notes were published in Mexico in 1604 and 1614, describing many animals to Europeans for the first time: coyote, buffalo, axolotl, porcupine, pronghorn antelope, horned lizard, bison, peccary, and the toucan. He also included figures of many animals for the first time, including the ocelot, rattlesnake, manatee, alligator, armadillo, and pelican.

- 1607 (1612?). Captain John Smith (English), head of the Jamestown colony, wrote A Map of Virginia in which he describes the physical features of the country, its climate, plants and animals, and inhabitants. He describes the raccoon, muskrat, flying squirrel, and other animals.

- 1617. .

- 1620? North American colonists probably introduced the European honeybee, Apis mellifera, into Virginia. By the 1640s these insects were also in Massachusetts. They became feral and advanced through eastern North America before the settlers.

- 1628. William Harvey (English, 1578–1657) published Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (1628) with the doctrine of the circulation of blood (an inference made by him in about 1616).

- 1634. William Wood (English) wrote New England Prospect (1634) in which he describes New England's fauna.

- 1637. Thomas Morton (English, c. 1579–1647) wrote New English Canaan (1637) with treatments of 26 species of mammals, 32 birds, 20 fishes and 8 marine invertebrates.

- 1648. Georg Marcgrave (1610–1644) was a German astronomer working for Johann Moritz, Count Maurice of Nassau, in the Dutch colony set up in northeastern Brazil. His Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (1648) contains the best early descriptions of many Brazilian animals. Marcgrave used Tupi names that were later Latinized by Linnaeus in the 13th edition of the Systema Naturae. The biological and linguistic data could have come from Moraes, a Brazilian Jesuit priest turned apostate.

- 1651. William Harvey published Exercitationes de Generatione Animalium (1651) with the aphorism Ex ovo omnia on the title page.

- 1661. Marcello Malpighi (Italian, 1628–1694) discovered capillaries (1661), structures predicted to exist by Harvey some thirty years earlier. Malpighi was the founder of microanatomy. He studied, among other things, the anatomy of the silkworm (1669) and the development of the chick (1672).

- 1665. Robert Hooke (English, 1635–1703) wrote Micrographia (1665, 88 plates), with his early microscopic studies. He coined the term "cell".

- 1668. Opening of the Royal Menagerie at Palace of Versailles.

- 1668. Francesco Redi (Italian, 1621–1697) wrote Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degli Insetti (1668) and De animaculis vivis quae in corpribus animalium vivorum reperiuntur (1708). His refutation of spontaneous generation in flies is still considered a model in experimentation.

- 1669. Jan Swammerdam (Dutch, 1637–1680) wrote Historia Insectorum Generalis (1669) describing metamorphosis in insects and supporting the performation doctrine. He was a pioneer in microscopic studies. He gave the first description of red blood corpuscles and discovered the valves of lymph vessels. His work was unknown and unacknowledged until after his death.

- 1672. Regnier de Graaf (Dutch, 1641–1673) reported that he had traced the human egg from the ovary down the fallopian tube to the uterus. What he really saw was the follicle.

- 1675–1722. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (Dutch, 1632–1723) wrote Arcana Naturae Detectae Ope Microscopiorum Delphis Batavorum, a treatise with early observations made with microscopes. He discovered blood corpuscles, striated muscles, human spermatozoa (1677), protozoa (1674), bacteria (1683), rotifers, etc.

- Martin Lister (English, 1639–1712) publishes the first work on spiders based on observation.

- 1691. John Ray (English, 1627–1705) wrote Synopsis methodica animalium quadripedum (1693), Historia Insectorum (1710), and The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation (1691). He tried to classify different animal species into groups largely according to their toes and teeth.

- 1699. .

- 1700. Félix de Azara (Spanish) estimated the feral herds of cattle on the South American pampas at 48 million animals. These animals probably descended from herds introduced by the Jesuits some 100 years earlier. (North America and Australia were to follow in this pattern, where feral herds of cattle and mustangs would explode, become pests, and reform the frontier areas.)

18th Century

- 1705. Fulgora lanternariawas luminous.

- 1734–1742. René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (French, 1683–1756) was an early entomologist. His Mémoires pour servir ... l'histoire des insectes (6 volumes) shows the best of zoological observation at the time. He invented the glass-fronted bee hive.

- 1740. Abraham Trembley, Swiss naturalist, discovered the hydra which he considered to combine both animal and plant characteristics. His Mémoires pour Servir ... l'Histoire d'un Genre de Polypes d'Eau Douce ... Bras en Terme de Cornes (1744) showed that freshwater polyps of Hydra could be sectioned or mutilated and still reform. Regeneration soon became a topic of inquiry among Réaumur, Bonnet, Spallanzani, and others.

- 1745. Charles Bonnet (French-Swiss, 1720–1793) wrote Traité d'Insectologie (1745) and Contemplation de la nature (1732). He confirmed parthenogenesis of aphids.

- 1745. arc of the meridian (1736–1737). Maupertuis was a Newtonian. He generated family trees for inheritable characteristics (e.g., haemophilia in European royal families) and showed inheritance through both the male and female lines. He was an early evolutionist and head of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. In 1744 he proposed the theory that molecules from all parts of the body were gathered into the gonads (later called "pangenesis"). Vénus physique was published anonymously in 1745. Maupertuis wrote Essai de cosmologie in which he suggests a survival of the fittestconcept: "Could not one say that since, in the accidental combination of Nature's productions, only those could survive which found themselves provided with certain appropriate relationships, it is no wonder that these relationships are present in all the species that actually exist? These species which we see today are only the smallest part of those which a blind destiny produced."

- 1748. John Tuberville Needham, an English naturalist, wrote Observations upon the Generation, Composition, and Decomposition of Animal and Vegetable Substances in which he offers "proof" of spontaneous generation. Needham found flasks of broth teeming with "little animals" after having boiled them and sealed them, but his experimental techniques were faulty.

Jardin des Plantes

in Paris.- 1749–1804. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (French, 1707–1788) wrote Histoire Naturelle (1749–1804 in 44 vols.), which asserted that species were mutable. Buffon also drew attention to vestigial organs. He held that spermatozoa were "living organic molecules" that multiplied in the semen.

- 1752. Founding of the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna, the world's oldest continuously operating zoo.

- 1753. The British Museum was founded in the will of Sir Hans Sloane (English (born Ireland), 1660–1753). It would open its doors in 1759.

- 1758. Albrecht von Haller (Swiss, 1708–1777) was one of the founders of modern physiology. His work on the nervous system was revolutionary. He championed animal physiology, along with human physiology. See his textbook Elementa Physiologiae Corporis Humani (1758).

- 1758. Carl Linnaeus (Swedish, 1707–1778) published the Systema Naturae whose tenth edition (1758) is the starting point of binomial nomenclature for zoology.

- 1759. Caspar Friedrich Wolff (1733–1794) wrote Theoria Generationis (1759) that disagreed with the idea of preformation. He supported the doctrine of epigenesis as a way to resolve the problem of hybrids (mule, hinny, apemen) in preformation.

- 1769. Edward Bancroft (English) wrote An Essay on the Natural History of Guyana in South America (1769)[3] and advanced the theory that flies transmit disease.

- 1771. Johann Reinhold Forster (German, 1729–1798) was the naturalist on Cook's second voyage around the world (1772–1775). He published a Catalogue of the Animals of North America (1771)[4] as an addendum to Kalm's Travels. He also studied the birds of Hudson Bay.

- 1774. flocking.

- 1774. European lanceletis described.

- 1775. Johan Christian Fabricius (Danish, 1745–1808) wrote Systema Entomologiae (1775), Genera Insectorum (1776), Philosophia Entomologica (1778), Entomologia Systematica (1792–1794, in six vols.), and later publications (to 1805), to make Fabricius one of the world's greatest entomologists.

- 1780. Lazaro Spallanzani (Italian, 1729–1799) performed artificial fertilization in the frog, silkmoth and dog. He concluded from filtration experiments that spermatozoa were necessary for fertilization. In 1783 he showed that human digestion was a chemical process since gastric juices in and outside the body liquefied food (meat). He used himself as the experimental animal. His work to disprove spontaneous generation in microbes was resisted by John Needham(English priest, 1713–1781).

- 1780. Pierre Laplace (French, 1749–1827) wrote Memoir on heat.[5] Lavoisier, the discoverer of oxygen, concluded that animal respiration was a form of combustion.

Eulemur mongoz

, plate from Johann Schreber's Histoire naturelle des quadrupèdes représentés d´après nature- 1783–1792. Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira (Brazilian) wrote Viagem Filosófica pelas Captanias do Grão-Pará, Rio Negro, Mato Grosso e Cuiabá. His specimens were taken by Saint-Hilaire from Lisbon to the Paris Museum during the Napoleonic invasion of Portugal.

- 1784. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German) wrote Erster Entwurf einer Einleitung in die vergleichende Anatomie (1795) that promoted the idea of archetypes to which animals should be compared.

- 1784. Thomas Jefferson (American) wrote Notes on the State of Virginia (1784) that refuted some of Buffon's mistakes about New World fauna. As U.S. president, he dispatched the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the American West (1804).

- 1788. The First Fleet inaugurates British settlement of Australia. Knowledge of Australia's unique zoology, including marsupials and the platypus, would revolutionize Western zoology.

- 1789? Guillaume Antoine Olivier(French, 1756–1814) wrote Entomologie, or Histoire Naturelle des Insectes (1789).

- 1789. George Shaw & Frederick Polydore Nodder published The Naturalist's Miscellany: or coloured figures of natural objects drawn and described immediately from nature (1789–1813) in 24 volumes with hundreds of color plates.

- 1792. Jan Dzierżonthat drones come from unfertilized eggs and queen and worker bees come from fertilized eggs.

- 1793. The National Museum of Natural History, France is founded in Paris. It became a major center of zoological research in the early nineteenth century.

- 1793. in the dark.

- 1793. Christian Konrad Sprengel (1750–1816) wrote Das entdeckte Geheimniss der Natur im Bau und in der Befruchtung der Blumen (1793) that was a major work on insect pollination of flowers, previously discovered in 1721 by Philip Miller (1694–1771), the head gardener at Chelsea and author of the famous Gardener's Dictionary (1731–1804).

- 1794. Erasmus Darwin (English, grandfather of Charles Darwin) wrote Zoönomia, or the Laws of Organic Life (1794)[6] in which he advanced the idea that environmental influences could transform species.

- 1796–1829. Bonpland.

- 1797-1804. Publication of A History of British Birds by Thomas Bewick and Ralph Beilby in two volumes.

- 1798. Publication of Thomas Robert Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, a book important to both Darwin and Wallace.

- 1799. George Shaw (English) provided the first description of the duck-billed platypus.[7] Everard Home (1802) provided the first complete description.

- 1799–1803. Alexander von Humboldt (German, 1769–1859) and Aimé Jacques Alexandre Goujaud Bonpland (French) arrived in Venezuela in 1799. Humboldt's Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America during the years 1799–1804[8] and Kosmos were influential in his time.

- 1799. Georges Cuvier (French, 1769–1832) established comparative anatomy as a field. He also founded the science of paleontology. He wrote Leçons d'Anatomie Comparée (1801–1805), Le Règne Animal distribué d'après son organisation (1816), Ossemens Fossiles (1812–1813). He believed in the fixity of species and the Biblical Flood. His early Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux (1798) was influential, but it did not include Cuvier's major contributions to animal classification.

- 1799. American hunters killed the last bison on the Eastern coast of the United States, in Pennsylvania.

19th Century

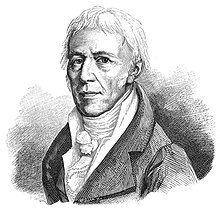

- 1802. Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (French, 1744–1829) wrote Recherches sur l'Organisation des Corps Vivants and Philosophie zoologique (1809). He was an early evolutionist and organized invertebrate paleontology. While Lamarck's contributions to science include work in meteorology, botany, chemistry, geology, and paleontology, he is best known for his work in invertebrate zoology and his theoretical work on evolution. He published a seven-volume work, Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres ("Natural history of animals without backbones"; 1815–1822).

- 1813–1818. William Charles Wells (Scottish-American, 1757–1817) was the first to recognise the principle of natural selection. He read a paper to the Royal Society in 1813 (but not published until 1818) which used the idea to explain differences between human races. The application was limited to the question of how different skin colours arose.

- 1815. William Kirby and William Spence (English) wrote An Introduction to Entomology (first edition in 1815). This was the first modern entomology text.

- 1817. Publication of American Entomology by Thomas Say, the first work devoted to American insects. A greatly expanded three-volume edition would appear 1824–1828. Say was a systematic zoologist who moved to the utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana, in 1825. Most of his insect collections have been recovered.

- 1817. Georges Cuvier wrote Le Règne Animal (Paris).

- 1817–1820. Johann Baptist von Spix (German, 1781–1826) and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (German) conducted Brazilian zoological and botanical explorations (1817–1820). See their Reise in Brasilien auf Befehl Sr. Majestät Maximilian Joseph I König von Bayern in den Jahren 1817 bis 1820 gemacht und beschrieben (3 vols., 1823–1831).

- 1817. William Smith, in his Strategraphical System of Organized Fossils (1817) showed that certain strata have characteristic series of fossils.

- 1819 soft inheritance), proto-evolutionary ideas about the origin of mankind, and a denial of the 'Jewish scriptures' (Old Testament). He was forced to suppress the book after the Lord Chancellor refused copyright and other powerful men made threatening remarks.

- 1819. Malayan tapir, a first species of tapir to be discovered, is described.

- 1824. Publication of the French physician Henri Dutrochet's Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire anatomique et physiologique des végétaux et des animaux setting forth a physiological theory of the cell.

- 1824. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) is founded at London.

- 1824. Founding of the Zoological Journal, the first English-language journal of zoology. The last issue would appear in 1834.

- 1825. dinosaurs. The name dinosaur was coined by anatomist Richard Owen.

- 1826. Founding of the Zoological Society of London.

- 1826–1839. John James Audubon (Haitian-born American, 1785–1851) wrote Birds of America (1826–1839), with North American bird portraits and studies. See also his posthumously published volume on North American mammals written with his sons and the naturalist John Bachman, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–1854) with 150 folio plates.

- 1827. Karl Ernst von Baer (Russian embryologist, 1792–1876) was the founder of comparative embryology. He demonstrated the existence of the mammalian ovum, and he proposed the germ-layer theory. His major works include De ovi mammalium et hominis genesi (1827) and Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Tiere (1828; 1837).

- 1827. Description of chaetognaths.

- 1828. The Zoological Society of London opens its "zoo" to the public (later known as the London Zoo) for two days a week beginning April 27, 1828, with the first hippopotamus to be seen in Europe since the ancient Romans showed one at the Colosseum. This was the first modern zoo founded for scientific research and education.

- 1829. James Smithson (English, 1765–1829) donates seed money in his will for the founding of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

- 1830–1833. Sir Charles Lyell (English, 1797–1875) writes Principles of Geology and described the time required for evolution to work. Darwin took this book to sea on HMS Beagle.

- 1830. Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (French, 1772–1844) writes Principes de philosophie zoologique (1830).

- 1830. Founding of the Journal of Zoology, then known as Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London.

- 1831. Founding of the Magasin de Zoologie, the first French-language zoological journal.

- 1831–1836. Charles Darwin (English, 1809–1882) and Captain Robert FitzRoy (English) depart for their voyage. Darwin's report is generally known as The Voyage of the Beagle.

- 1832. Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859) writes A Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada (1832) that becomes the standard text on the subject for most of the 19th century.

- 1835. William Swainson (English, 1789–1855) writes A Treatise on the Geography and Classification of Animals (1835), in which he uses ad hoc land bridges to explain animal distributions. He includes some second-hand observations on Old World army ants.

- 1835. Founding of the Archiv für Naturgeschichte, the premier German-language journal of natural history with an emphasis on zoology. It would be published until 1926.

- 1839. Theodor Schwann (German, 1810–1882) writes Mikroskopischen Untersuchungen über die Übereinstimmungen in der Strucktur und dem Wachstum der Thiere und Pflanzen (1839). Schwann established the foundation for cell theory.

- 1839. Louis Agassiz (Swiss-American, 1807–1873), an expert on fossil fishes, founds the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and becomes Darwin's North American opposition. He was a popularizer of natural history. His Nomenclator Zoologicus (1842–1847) was a pioneering effort.

- 1840. Jan Evangelista Purkyně, a Czech physiologist in Wrocław proposes that the word "protoplasm" be applied to the formative material of young animal embryos.

- 1842. Baron Justus von Liebig writes Die Thierchemie in which he suggests that animal heat is produced by combustion, and founds the science of biochemistry.

- 1843. John James Audubon, age 58, ascends the Missouri River to Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone to sketch wild animals.

- 1844. Berlin Zoo is founded.

- 1844. Robert Chambers (Scottish, 1802–1871) writes the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation(1844) in which he includes early evolutionary considerations. This book, anonymously published, has a profound effect on Alfred Russel Wallace.

- 1845. von Siebold recognizes Protozoa as single-celled animals.

- 1848. Josiah C. Nott (American), a physician from New Orleans, publishes his belief that mosquitoes transmit malaria.

- 1848. Henry W. Bates (English, 1825–1892) arrive in the Amazon River valley in 1848. Bates stays until 1859, exploring the upper Amazon. Wallace remains in the Amazon until 1852, exploring the Rio Negro. Wallace writes A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro (1853), and Bates writes The Naturalist on the River Amazons (1863). Later (1854–1862), Wallace travels to the Far East, as he reports in The Malay Archipelago(1869).

- 1849. Arnold Adolph Berthold demonstrates by castration and testicular transplant that the testis produces a blood-borne substance promoting male secondary sexual characteristics.

- 1850. lesser panda(Ailurus fulgens) in northern India.

- 1855. Alfred Russel Wallace (English, 1823–1913) publishes On the law which has regulated the introduction of new species (Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist., September 1855), with evolutionary ideas that drew upon Wallace's experiences in the Amazon.

- 1857–1881. Henri Milne-Edwards (French, 1800–1885) introduces the idea of physiologic division of labor and writes a treatise on comparative anatomy and physiology (1857–1881).

- 1859. Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species, explaining the mechanism of evolution by natural selection and founding the field of evolutionary biology.

- Founding of Copenhagen Zoo.

- 1864. Louis Pasteur disproves the spontaneous generation of cellular life.

- 1864. Founding of the Moscow Zoo.

- 1865. definite rules. The Principle of Segregation states that each organism has two genesper trait, which segregate when the organism makes eggs or sperm. The Principle of Independent Assortment states that each gene in a pair is distributed independently during the formation of eggs or sperm. Mendel's observations went largely unnoticed.

- 1868. Founding of the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, Illinois.

- 1869. Friedrich Miescher discovers nucleic acids in the nuclei of cells.

- 1872. Darwin publishes The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

- 1873. Founding of the Cincinnati Zoo.

- 1876. Oskar Hertwig and Hermann Fol independently describe (in sea urchineggs) the entry of sperm into the egg and the subsequent fusion of the egg and sperm nuclei to form a single new nucleus.

- 1876. Founding of the Société zoologique de France.

- 1878. Founding of the Zoological Society of Japan.

- 1881. Przewalski's horse is described.

- 1885. cnidarian, is described.

- 1889. Founding of the National Zoological Park (United States) as part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

- 1889. The first species of marsupial mole is described.

- 1892. Hans Driesch separates the individual cells of a 2-cell sea urchin embryo, and shows that each cell develops into a complete individual, thus disproving the theory of preformation, and demonstrating that each cell is "totipotent," containing all the hereditary information necessary to form an individual.

- 1895. Founding of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, the body which continues to govern zoological nomenclature.

- 1899. Founding of the Bronx Zoo.

- 1900. Three biologists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, Erich von Tschermak, independently rediscover Mendel's paper on heredity.[9]

- 1900. Founding of the Unione Zoologica Italiana.

- 1900. First species of Siboglinidae discovered.

20th Century

1901–1950

- 1901. Okapi is described for science.

- 1905. William Bateson coins the term "genetics" to describe the study of biological inheritance.[10]

- 1906. Founding of the Beijing Zoo.

- 1907. Ivan Pavlov demonstrates conditioned responses with salivating dogs.

- 1907. First species of proturans are described.

- 1910. Founding of the Saint Louis Zoo.

- 1914. Grylloblattodeais discovered.

- 1916. Founding of the San Diego Zoo.

- 1916. Founding of the Zoological Survey of India.

- 1922. origin of life.

- 1931. Founding of Prague Zoo.

- 1932. Founding of the Journal of Animal Ecology.

- 1932. Establishment of the Bureau of Animal Population at the University of Oxford.

- 1934. Brookfield Zoo is founded in Brookfield, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

- 1935. Konrad Lorenz describes the imprinting behavior of young birds.[11]

- 1936. Founding of the National Zoological Gardens of Sri Lanka.

- 1937. In Genetics and the Origin of Species, Theodosius Dobzhansky applies the chromosome theory and population genetics to natural populations in the first mature work of Neo-Darwinism, also called the modern synthesis, a term coined by Julian Huxley.

- 1938. A living coelacanth is found off the coast of southern Africa.

- 1940. Donald Griffin and Robert Galambos announce their discovery of echolocation by bats.[12]

1951–2000

- 1952. American developmental biologists Robert Briggs and Thomas King clone the first vertebrate by transplanting nuclei from leopard frog embryos into enucleated eggs.

- 1952. Monoplacophorans, so far considered extinct, are found to be still present today.

- 1955. First species from crustacean class Cephalocarida is discovered.

- 1956. First gnathostomulids, a group of animals currently ranked as a phylum, are described.

- 1959. Founding of the National Zoological Park Delhi in New Delhi, India.

- 1960. Jane Goodall begins her chimpanzee research.

- 1961. origin of life.

- 1963. Founding of the National Zoo of Malaysia in Selangor.

- 1963. Premier of the popular American zoological documentary series Wild Kingdom on the NBC television network. 140 episodes would appear before the series ended in 1988.

- 1964. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) issues its first IUCN Red List of species threatened by extinction.

- 1967. clawed frog; first cloning of a vertebrate using a nucleus from a fully differentiatedadult cell.

- 1972. Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge propose "punctuated equilibrium," a theory which states that the fossil record is an accurate depiction of the pace of evolution, with long periods of "stasis" (little change) punctuated by brief periods of rapid change and species divergence.

- 1973. Passage of the U. S. Endangered Species Act of 1973.

- 1977. Riftia pachyptila, the giant tube worm, discovered.

- 1980. Founding of PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

- 1980. Lobatocerebridae, a group of simple, unsegmented annelids with relatively complex brain, are described.[13]

- 1981. The first extant members of remipedes, a new class of crustaceans, are discovered.

- 1983. A new class of crustaceans, Tantulocarida, is proposed.

- 1983. First species of loriciferans are described.

- 1985. The primatologist Dian Fossey is murdered by poachers.

- 1986. Sea daisies, a group of unusual starfishes, are discovered.

- 1990. American entomologist E. O. Wilson and German entomologist Bert Hölldobler publish The Ants. The next year it will win the Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction, the only zoology textbook ever to do so.

- 1992. Saola, a new species of ungulate, is discovered in Vietnam.

- 1995. Cycliophora, is described by Reinhardt Kristensen and Peter Funch.

- 1996. Dolly the sheepis the first adult mammal to be successfully cloned.

- 1999. Indonesian coelacanth, the second species of coelacanth, is described.

- 2000. Micrognathozoa.

- 2000. Kikiki huna, the smallest known flying insect, is described.

21st Century

- 2002. First species from Mantophasmatodeaare described.

- 2002. Founding of the Zoological Society of Nigeria.[14]

- 2003. deep-seaspecies of jellyfish, is described.

- 2004. Osedax, known also as bone-eating worm, a deep-sea species of Siboglinidae that feeds on bones of whale carcasses, is described.

- 2005. Mimic octopus is described.

- 2005. cubozoan, is described.

- 2006. Ping-pong Tree Sponge, an unusual species of carnivorous sponge, is described.

- 2006. Wunderpus is described.

- 2007. cubozoan, is described.

- 2011. Halicephalobus mephisto, a species of nematode living 3.6 km under the surface of Earth in gold mines in South Africa, is discovered.

- 2011. cubozoan, is described.

- 2012. Chondrocladia lyra, an unusual species of carnivorous sponge, is described.

- 2013. Edwardsiella andrillae, an unusual species of sea anemone that lives attached to sea ice, is described.

- 2016. Scolopendra cataracta, the first known species of amphibious centipede, is described.

- 2016. Four new species from subphylum Xenoturbellida (Xenoturbella bocki) was known before.

- 2017. Tapanuli orangutan is found to be a distinct species.

- 2017. deep-seaspecies of fish, is described.

- 2018. Hoilungia hongkongensis is described, the first species of placozoan to be discovered since 1883.

- 2019. Polyplacotoma mediterranea is described, the first species from the placozoan class Polyplacotomia.

- 2021. myriapodknown to have more than 1,000 legs is discovered.

See also

- Timeline of biology and organic chemistry

- List of megafauna discovered in modern times

- International Institute for Species Exploration

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

- Lazarus taxon

References

- ^ Charles A. Reed. Animal Domestication in the Prehistoric Near East: The origins and history of domestication are beginning to emerge from archeological excavations. Science, Vol. 130, no. 3389 (December 11, 1959), pp. 1629–1639

- ^ Lascaux, a visit to the cave.

- ^ Bancroft, Edward (1769). An Essay on the Natural History of Guiana, in South America: Containing a Description of Many Curious Productions in the Animal and Vegetable Systems of that Country. Together with an Account of the Religion, Manners, and Customs of Several Tribes of Its Indian Inhabitants. Interspersed with a Variety of Literary and Medical Observations. T. Becket and P.A. De Hondt.

- ^ Forster, Johann Reinhold (1771). A catalogue of the animals of North America. To which are added short directions for collecting, preserving and transporting all kinds of natural history curiosities. B. White.

- ^ Lavoisier, Antoine Laurent; Laplace, Pierre Simon de (1982). Memoir on Heat: Read to the Royal Academy of Sciences, 28 June 1783. Neale Watson Acad. Publ.

- ^ Darwin, Erasmus (1809). Zoonomia; Or, The Laws of Organic Life: In Three Parts : Complete in Two Volumes. Thomas & Andrews.

- doi:10.5962/p.304567.

- ^ Humboldt, Alexander von; Bonpland, Aimé (1815). Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, During the Years 1799-1804. M. Carey, no. 121 Chesnut street. Dec. 23. [Geo. Phillips, Printer, Carlisle.]

- PMID 11147091– via Elsevier.

- S2CID 26806110– via Springer Link.

- JSTOR 4078077– via JSTOR.

- doi:10.1002/jez.1400860310 – via Wiley.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Alexandra Kerbl, Nicolas Bekkouche, Wolfgang Sterrer & Katrine Worsaae, "Detailed reconstruction of the nervous and muscular system of Lobatocerebridae with an evaluation of its annelid affinity", BMC Evolutionary Biology volume 15, Article number: 277 (2015), https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-015-0531-x

- ^ Zoological Society of Nigeria https://zoologicalsocietyofnigeria.com/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)