Djibouti

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Republic of Djibouti | ||

|---|---|---|

| Motto: Midnimo, Sinnaan, Nabad ( Prime Minister | Abdoulkader Kamil Mohamed | |

| Legislature | National Assembly | |

| Formation | ||

| 20 May 1883 | ||

| 5 July 1967 | ||

• Independence from France | 27 June 1977 | |

| 20 September 1977 | ||

| 4 September 1992 | ||

+253 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | DJ | |

| Internet TLD | .dj | |

Djibouti,[a] officially the Republic of Djibouti,[b] is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia[c] to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area of 23,200 km2 (8,958 sq mi).[1]

In antiquity, the territory, together with Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somaliland, was part of the

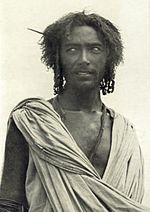

Djibouti is a multi-ethnic nation with a population of over 920,000 (

Djibouti is near some of the world's busiest shipping lanes, controlling access to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. It serves as a key refuelling and transshipment center, and the principal maritime port for imports from and exports to neighboring Ethiopia. A burgeoning commercial hub, the nation is the site of various foreign military bases. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) regional body also has its headquarters in Djibouti City.[1]

Name and etymology

Djibouti is officially known as the Republic of Djibouti. In local languages it is known as Yibuuti (in Afar) and Jabuuti (in Somali).

The country is named for its capital, the

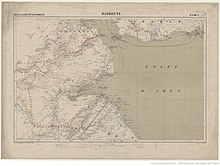

From 1862 until 1894, the land to the north of the Gulf of Tadjoura was called "Obock". Under French administration, from 1883 to 1967 the area was known as French Somaliland (French: Côte française des Somalis), and from 1967 to 1977 as the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas (French: Territoire français des Afars et des Issas).

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

Prehistory

The Bab-el-Mandeb region has often been considered a primary crossing point for early hominins following a southern coastal route from East Africa to South and Southeast Asia.

The Djibouti area has been inhabited since the

Cut stones dated about 3 million years old have been collected in the area of

Pottery predating the mid-2nd millennium has been found at

The site of Wakrita is a small Neolithic establishment located on a wadi in the tectonic depression of Gobaad in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. The 2005 excavations[citation needed] yielded abundant ceramics that enabled us to define one Neolithic cultural facies of this region, which was also identified at the nearby site of Asa Koma. The faunal remains confirm the importance of fishing in Neolithic settlements close to Lake Abbé, but also the importance of bovine husbandry and, for the first time in this area, evidence for caprine herding practices. Radiocarbon dating places this occupation at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, similar in range to Asa Koma. These two sites represent the oldest evidence of herding in the region, and they provide a better understanding of the development of Neolithic societies in this region.

Up to 4000 years BCE, the region benefited from a climate very different from the one it knows today and probably close to the

Punt (2,500 BCE)

Together with northern Ethiopia, Somaliland, Eritrea and the Red Sea coast of Sudan, Djibouti is considered the most likely location of the territory known to the Ancient Egyptians as Punt (or Ta Netjeru, meaning "God's Land"). The first mention of the Land of Punt dates to the 25th century BC.[28] The Puntites were a nation of people who had close relations with Ancient Egypt during the reign of the 5th dynasty Pharaoh Sahure and the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut.[29] According to the temple murals at Deir el-Bahari, the Land of Punt was ruled at that time by King Parahu and Queen Ati.[30]

Adal (900–1285)

The Adal (also Awdal, Adl, or Adel)

In the late 9th century,

Ifat Sultanate (1285–1415)

Through close contacts with the adjacent Arabian Peninsula for more than 1,000 years, the Somali and Afar ethnic groups in the region became among the first populations on the continent to embrace Islam.

Adal Sultanate (1415–1577)

According to the 16th-century explorer

Ottoman Eyalet (1577–1867)

Although nominally part of the Ottoman Empire since 1577, between 1821 and 1841, Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt, came to control Yemen, Harar, Gulf of Tadjoura with Zeila and Berbera included. The Governor Abou Baker ordered the Egyptian garrison at Sagallo to retire to Zeila. The cruiser Seignelay reached Sagallo shortly after the Egyptians had departed. French troops occupied the fort despite protests from the British Agent in Aden, Major Frederick Mercer Hunter, who dispatched troops to safeguard British and Egyptian interests in Zeila and prevent further extension of French influence in that direction.[50]

On 14 April 1884 the Commander of the patrol sloop L'Inferent reported on the Egyptian occupation in the Gulf of Tadjoura. The Commander of the patrol sloop Le Vaudreuil reported that the Egyptians were occupying the interior between Obock and Tadjoura. Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia signed an accord with Great Britain to cease fighting the Egyptians and to allow the evacuation of Egyptian forces from Ethiopia and the Somaliland littoral. The Egyptian garrison was withdrawn from Tadjoura. Léonce Lagarde deployed a patrol sloop to Tadjoura the following night.

French rule (1883–1977)

The boundaries of the present-day Djibouti state were established as the first French establishment in the

Although the population fell after the completion of the railwayline to

.After the Italian

British and Commonwealth forces fought the neighboring Italians during the

In 1958, on the eve of neighboring Somalia's independence in 1960, a

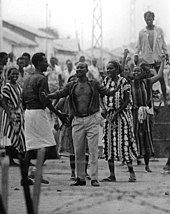

In 1966, France rejected the United Nations' recommendation that it should grant French Somaliland independence. In August of the same year, an official visit to the territory by then French President Charles de Gaulle, was also met with demonstrations and rioting.[13][63] In response to the protests, de Gaulle ordered another referendum.[63]

In 1967, a

During the 1960s, the struggle for independence was led by the

In 1976, members of the

Djibouti Republic

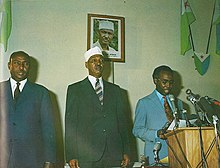

A

During its first year, Djibouti joined the

In the early 1990s, tensions over government representation led to armed conflict between Djibouti's ruling People's Rally for Progress (PRP) party and the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD) opposition group. The impasse ended in a power-sharing agreement in 2000.[1]

In April 2021,

Politics

Djibouti is a

Governance

The

The judicial system consists of courts of first instance, a High Court of Appeal, and a Supreme Court. The

The National Assembly (formerly the Chamber of Deputies) is the country's legislature, The

The government is dominated by the Somali

President Guelleh succeeded

On 31 March 2013, Guelleh replaced long-serving Prime Minister

Foreign relations

Foreign relations of Djibouti are managed by the Djiboutian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. Djibouti maintains close ties with the governments of Somalia, Ethiopia, France and the United States. It is likewise an active participant in African Union, United Nations, Non-Aligned Movement, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and Arab League affairs. Since the 2000s, Djiboutian authorities have also strengthened relations with Turkey.

Djibouti has been a member of

Military

The

database). After independence, Djibouti had two regiments commanded by French officers. In the early 2000s, it looked outward for a model of army organization that would best advance defensive capabilities by restructuring forces into smaller, more mobile units instead of traditional divisions.The first war to involve the Djiboutian Armed Forces was the Djiboutian Civil War between the Djiboutian government, supported by France, and the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD). The war lasted from 1991 to 2001, although most of the hostilities ended when the moderate factions of FRUD signed a peace treaty with the government after suffering an extensive military setback when the government forces captured most of the rebel-held territory. A radical group continued to fight the government, but signed its own peace treaty in 2001. The war ended in a government victory, and FRUD became a political party.

As the headquarters of the IGAD regional body, Djibouti has been an active participant in the Somali peace process, hosting the Arta conference in 2000.[83] Following the establishment of the Federal Government of Somalia in 2012,[84] a Djiboutian delegation attended the inauguration ceremony of Somalia's new president.[85]

In recent years, Djibouti has improved its training techniques, military command and information structures and has taken steps to becoming more self-reliant in supplying its military to collaborate with the United Nations in peacekeeping missions, or to provide military help to countries that officially ask for it. Now deployed to Somalia and Sudan.[86]

Foreign military presence

The French Forces remained present in Djibouti when the territory gained independence, first as part of a provisional protocol of June 1977 laying down the conditions for the stationing of French forces, constituting a defense agreement. A new defence cooperation treaty between France and Djibouti was signed in Paris on 21 December 2011. It entered into force on 1 May 2014. By that treaty and its security clause, France reaffirmed its commitment to the independence and territorial integrity of the Republic of Djibouti. As well before independence, in 1962, a French Foreign Legion unit, the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion (13 DBLE) was transferred from Algeria to Djibouti to form the core of the French garrison there.[87] On 31 July 2011, the (13 DBLE) left Djibouti to the United Arab Emirates.

Djibouti's strategic location by the

The hosting of foreign military bases is an important part of Djibouti's economy. The United States pays $63 million a year to rent Camp Lemonnier,[89] France and Japan each pay about $30 million a year,[91] and China pays $20 million a year.[89] The lease payments added up to more than 5% of Djibouti's GDP of US$2.3 billion in 2017.[citation needed]

China has, in recent times, stepped up its military presence in Africa, with ongoing plans to secure an even greater military presence in Djibouti specifically. China's presence in Djibouti is tied to strategic ports to ensure the security of Chinese assets. Djibouti's strategic location makes the country prime for an increased military presence.[92]

Human rights

In its 2011 Freedom in the World report, Freedom House ranked Djibouti as "Not Free", a downgrading from its former status as "Partly Free".

According to the 2019 U.S. State Department

Administrative divisions

Djibouti is partitioned into six administrative regions, with

| Region | Area (km2) | Population 2009 census |

Population 2018 estimate |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali Sabieh | 2,200 | 86,949 | 96,500 | Ali Sabieh |

| Arta | 1,800 | 42,380 | 72,200 | Arta |

| Dikhil | 7,200 | 88,948 | 105,300 | Dikhil |

| Djibouti | 200 | 475,322 | 603,900 | Djibouti City |

| Obock | 4,700 | 37,856 | 50,100 | Obock |

| Tadjourah | 7,100 | 86,704 | 121,000 | Tadjoura |

Geography

Location and habitat

Djibouti is in the Horn of Africa, on the Gulf of Aden and the Bab-el-Mandeb, at the southern entrance to the Red Sea. It lies between latitudes 11° and 14°N and longitudes 41° and 44°E, at the northernmost point of the Great Rift Valley. It is in Djibouti that the rift between the African Plate and the Somali Plate meets the Arabian Plate, forming a geologic tripoint.[94] The tectonic interaction at this tripoint has created the lowest elevation of any place in Africa at Lake Assal, and the second-lowest depression on dry land anywhere on earth (surpassed only by the depression along the border of Jordan and Israel).

The country's coastline stretches 314 kilometres (195 miles), with terrain consisting mainly of plateau, plains and highlands. Djibouti has a total area of 23,200 square kilometres (8,958 sq mi). Its borders extend 575 km (357 mi), 125 km (78 mi) of which are shared with

Djibouti has eight mountain ranges with peaks of over 1,000 metres (3,300 feet).[96] The Mousa Ali range is considered the country's highest mountain range, with the tallest peak on the border with Ethiopia and Eritrea. It has an elevation of 2,028 metres (6,654 feet).[96] The Grand Bara desert covers parts of southern Djibouti in the Arta, Ali Sabieh and Dikhil regions. The majority of it sits at a relatively low elevation, below 1,700 feet (520 metres).

Extreme geographic points include: to the north, Ras Doumera and the point at which the border with Eritrea enters the Red Sea in the Obock Region; to the east, a section of the Red Sea coast north of Ras Bir; to the south, a location on the border with Ethiopia west of the town of

Most of Djibouti is part of the

- Landscapes of Djibouti

-

Traditional houses on the Mabla Mountains

-

The mountains near Dasbiyo

-

Beach south of Djibouti City, overlooking the Gulf of Aden

Climate

Djibouti's

Djibouti's climate ranges from

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djibouti City | 41/31 | 107/88 | 28/21 | 83/70 |

| Ali Sabieh | 36/25 | 96/77 | 26/15 | 79/60 |

| Tadjoura | 41/31 | 107/88 | 29/22 | 84/72 |

| Dikhil | 38/27 | 100/81 | 27/17 | 80/63 |

| Obock | 41/30 | 105/87 | 28/22 | 84/72 |

| Arta | 36/25 | 97/78 | 25/15 | 78/60 |

| Randa | 34/23 | 94/73 | 23/13 | 74/56 |

| Holhol | 38/28 | 101/81 | 26/17 | 79/62 |

| Ali Adde | 38/27 | 100/82 | 26/16 | 80/61 |

| Airolaf | 31/18 | 88/66 | 22/9 | 71/49 |

Wildlife

The country's flora and fauna live in a harsh landscape with forest accounting for less than one percent of the total area of the country.[99] Wildlife is spread over three main regions, namely from the northern mountain region of the country to the volcanic plateaux in its southern and central part and culminating in the coastal region.

Most species of wildlife are found in the northern part of the country, in the ecosystem of the

According to the country profile related to biodiversity of wildlife in Djibouti, the nation contains more than 820 species of plants, 493 species of invertebrates, 455 species of fish, 40 species of reptiles, three species of amphibians, 360 species of birds and 66 species of mammals.

Economy

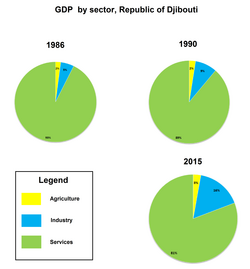

Djibouti's economy is largely concentrated in the service sector. Commercial activities revolve around the country's free trade policies and strategic location as a Red Sea transit point. Due to limited rainfall, vegetables and fruits are the principal production crops, and other food items require importation. The GDP (purchasing power parity) in 2013 was estimated at $2.505 billion, with a real growth rate of 5% annually. Per capita income is around $2,874 (PPP). The services sector constituted around 79.7% of the GDP, followed by industry at 17.3%, and agriculture at 3%.[1]

As of 2013[update], the container terminal at the

Djibouti was ranked the 177th safest investment destination in the world in the March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings.[106] To improve the environment for direct foreign investment, the Djibouti authorities in conjunction with various non-profit organizations have launched a number of development projects aimed at highlighting the country's commercial potential. The government has also introduced new private sector policies targeting high interest and inflation rates, including relaxing the tax burden on enterprises and allowing exemptions on consumption tax.[105] Additionally, efforts have been made to lower the estimated 60% urban unemployment rate by creating more job opportunities through investment in diversified sectors. Funds have especially gone toward building telecommunications infrastructure and increasing disposable income by supporting small businesses. Owing to its growth potential, the fishing and agro-processing sector, which represents around 15% of GDP, has also enjoyed rising investment since 2008.[105]

To expand the modest industrial sector, a 56 megawatt geothermal power plant slated to be completed by 2018 is being constructed with the help of

The Djibouti firm Salt Investment (SIS) began a large-scale operation to industrialize the plentiful salt in Djibouti's Lake Assal region. Operating at an annual capacity of 4 million tons, the desalination project has lifted export revenues, created more job opportunities, and provided more fresh water for the area's residents.[1][105] In 2012, the Djibouti government also enlisted the services of the China Harbor Engineering Company Ltd for the construction of an ore terminal. Worth $64 million, the project enabled Djibouti to export a further 5,000 tons of salt per year to markets in Southeast Asia.[107]

Djibouti's gross domestic product expanded by an average of more than 6 percent per year, from US$341 million in 1985 to US$1.5 billion in 2015. The

As of 2010[update], 10 conventional and Islamic banks operate in Djibouti. Most arrived within the past few years, including the Somali money transfer company Dahabshiil and BDCD, a subsidiary of Swiss Financial Investments. The banking system had previously been monopolized by two institutions: the Indo-Suez Bank and the Commercial and Industrial Bank (BCIMR).[108] To assure a robust credit and deposit sector, the government requires commercial banks to maintain 30% of shares in the financial institution;[clarification needed] a minimum of 300 million Djiboutian francs in up-front capital is mandatory for international banks. Lending has likewise been encouraged by the creation of a guarantee fund, which allows banks to issue loans to eligible small- and medium-sized businesses without first requiring a large deposit or other collateral.[105]

Saudi investors are also reportedly exploring the possibility of linking the Horn of Africa with the Arabian Peninsula via a 28.5-kilometre-long (17.7 mi)[110] oversea bridge through Djibouti, referred to as the Bridge of the Horns. The investor Tarek bin Laden has been linked to the project. In June 2010, Phase I of the project was delayed.[111]

Transport

The Djibouti–Ambouli International Airport in Djibouti City, the country's only international airport, serves many intercontinental routes with scheduled and chartered flights. Air Djibouti is the flag carrier of Djibouti and is the country's largest airline.

The new and electrified

Car ferries pass the Gulf of Tadjoura from Djibouti City to Tadjoura. There is the Port of Doraleh west of Djibouti City, which is the main port of Djibouti. The Port of Doraleh is the terminal of the new Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway. In addition to the Port of Doraleh, which handles general cargo and oil imports, Djibouti (2018) has three other major ports for the import and export of bulk goods and livestock, the Port of Tadjourah (potash), the Damerjog Port (livestock) and the Port of Goubet (salt). Almost 95% of Ethiopia's imports and exports move through Djiboutian ports.[citation needed]

The Djiboutian highway system is named according to the road classification. Roads that are considered primary roads are those that are fully asphalted (throughout their entire length) and in general they carry traffic between all the major towns in Djibouti.

Djibouti is part of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast to the Upper Adriatic region with its connections to Central and Eastern Europe.[112][113][114][115][116]

Media and telecommunications

Telecommunications in Djibouti fall under the authority of the Ministry of Communication.[117]

Radio Television of Djibouti is the state-owned national broadcaster. It operates the sole terrestrial TV station, as well as the two domestic radio networks on AM 1, FM 2, and shortwave 0. Licensing and operation of broadcast media is regulated by the government.[1] Movie theaters include the Odeon Cinema in the capital.[118]

As of 2012[update], there were 215 local internet service providers. Internet users comprised around 99,000 individuals (2015). The internet country top-level domain is .dj.[1]

The main print newspapers are owned by the government: the French-language daily La Nation, the English weekly Djibouti Post, and the Arabic weekly Al-Qarn. There is also a state news agency, Agence Djiboutienne d'Information. Non-government news websites are based abroad; for instance, La Voix de Djibouti operates out of Belgium.[119]

Tourism

Tourism in Djibouti is one of the growing economic sectors of the country and is an industry that generates less than 80,000 arrivals per year, mostly the family and friends of the soldiers stationed in the country's major naval bases.[120] Although the numbers are on the rise, there are talks of the visa on arrival being stopped, which could limit tourism growth.

Infrastructure makes it difficult for tourists to travel independently and costs of private tours are high. Since the re-opening of the train line from Addis Ababa to Djibouti in January 2018,[121] travel by land has also resumed. Djibouti's two main geological marvels, Lake Abbe and Lake Assal, are the country's top tourist destinations. The two sites draw[122] hundreds of tourists every year looking for remote places that are not visited by many.

Energy

Djibouti has an installed electrical power generating capacity of 126 MW from fuel oil and diesel plants.[123] In 2002 electrical power output was put at 232 GWh, with consumption at 216 GWh. At 2015, per capita annual electricity consumption is about 330 kilowatt-hours (kWh); moreover, about 45% of the population does not have access to electricity,[123] and the level of unmet demand in the country's power sector is significant. Increased hydropower imports from Ethiopia, which satisfies 65% of Djibouti's demand, will play a significant role in boosting the country's renewable energy supply.[123] The geothermal potential has generated particular interest in Japan, with 13 potential sites; they have already started the construction on one site near Lake Assal. The construction of the photovoltaic power station (solar farms) in Grand Bara will generate 50 MW capacity.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 62,001 | — |

| 1955 | 69,589 | +2.34% |

| 1960 | 83,636 | +3.75% |

| 1965 | 114,963 | +6.57% |

| 1970 | 159,659 | +6.79% |

| 1977 | 277,750 | +8.23% |

| 1980 | 358,960 | +8.93% |

| 1985 | 425,613 | +3.47% |

| 1990 | 590,398 | +6.76% |

| 1995 | 630,388 | +1.32% |

| 2000 | 717,584 | +2.62% |

| 2005 | 784,256 | +1.79% |

| 2010 | 850,146 | +1.63% |

| 2015 | 869,099 | +0.44% |

| 2018 | 884,017 | +0.57% |

| Source: World Bank[124] | ||

Djibouti has a population of about 921,804 inhabitants.

Languages of Djibouti Arabic (2%) Other (3%)

|

Islam in Djibouti (Pew)[130] Shiaism (2%) |

Languages

Djibouti is a

Arabic is of religious importance. In formal settings, it consists of

Religion

Djibouti's population is predominantly

Islam entered the region very early on, as a group of persecuted Muslims had sought refuge across the

The

Largest cities

| Rank | Name | Region | Municipal pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Djibouti |

Djibouti | 475,322 |  Dikhil  Tadjoura | |||||

| 2 | Ali Sabieh | Ali Sabieh | 37,939 | ||||||

| 3 | Dikhil | Dikhil | 24,886 | ||||||

| 4 | Tadjoura | Tadjourah | 14,820 | ||||||

| 5 | Arta | Arta | 13,260 | ||||||

| 6 | Obock | Obock | 11,706 | ||||||

| 7 | Ali Adde | Ali Sabieh | 3,500 | ||||||

| 8 | Holhol | Ali Sabieh | 3,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Airolaf | Tadjourah | 1,023 | ||||||

| 10 | Randa | Tadjourah | 1,023 | ||||||

Health

The life expectancy at birth is around 64.7 for both males and females. Fertility is at 2.35 children per woman.[1] In Djibouti there are about 18 doctors per 100,000 persons.[139]

The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Djibouti is 300. This is compared with 461.6 in 2008 and 606.5 in 1990. The under 5 mortality rate per 1,000 births is 95 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5's mortality are 37. In Djibouti the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is 6 and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women 1 in 93.[140]

About 93.1% of Djibouti's women and girls have undergone

Education

Education is a priority for the government of Djibouti. As of 2009[update], it allocates 20.5% of its annual budget to scholastic instruction.[148]

The Djiboutian educational system was initially formulated to cater to a limited pupil base. As such, the schooling framework was largely elitist and drew considerably from the French colonial paradigm, which was ill-suited to local circumstances and needs.[148]

In the late 1990s, the Djiboutian authorities revised the national educational strategy and launched a broad-based consultative process involving administrative officials, teachers, parents, national assembly members and NGOs. The initiative identified areas in need of attention and produced concrete recommendations on how to go about improving them. The government subsequently prepared a comprehensive reform plan aimed at modernizing the educational sector over the 2000–10 period. In August 2000, it passed an official Education Planning Act and drafted a medium-term development plan for the next five years. The fundamental academic system was significantly restructured and made compulsory; it now consists of five years of primary school and four years of middle school. Secondary schools also require a Certificate of Fundamental Education for admission. In addition, the new law introduced secondary-level vocational instruction and established university facilities in the country.[148]

As a result of the Education Planning Act and the medium-term action strategy, substantial progress has been registered throughout the educational sector.[148] In particular, school enrollment, attendance, and retention rates have all steadily increased, with some regional variation. From 2004 to 2005 to 2007–08, net enrollments of girls in primary school rose by 18.6%; for boys, it increased 8.0%. Net enrollments in middle school over the same period rose by 72.4% for girls and 52.2% for boys. At the secondary level, the rate of increase in net enrollments was 49.8% for girls and 56.1% for boys.[149]

The Djiboutian government has especially focused on developing and improving institutional infrastructure and teaching materials, including constructing new classrooms and supplying textbooks. At the post-secondary level, emphasis has also been placed on producing qualified instructors and encouraging out-of-school youngsters to pursue vocational training.[148] As of 2012[update], the literacy rate in Djibouti was estimated at 70%.[150]

Institutions of higher learning in the country include the University of Djibouti.

Culture

Djiboutian attire reflects the region's hot and arid climate. When not dressed in Western clothing such as jeans and T-shirts, men typically wear the macawiis, which is a traditional sarong-like garment worn around the waist. Many nomadic people wear a loosely wrapped white cotton robe called a tobe that goes down to about the knee, with the end thrown over the shoulder (much like a Roman toga).

Women typically wear the dirac, which is a long, light, diaphanous

A lot of Djibouti's original art is passed on and preserved orally, mainly through song. Many examples of Islamic, Ottoman, and French influences can also be noted in the local buildings, which contain plasterwork, carefully constructed motifs, and calligraphy.

Music

Somalis have a rich musical heritage centered on traditional Somali folklore. Most Somali songs are pentatonic. That is, they only use five pitches per octave in contrast to a heptatonic (seven note) scale such as the major scale. At first listen, Somali music might be mistaken for the sounds of nearby regions such as Ethiopia, Sudan or the Arabian Peninsula, but it is ultimately recognizable by its own unique tunes and styles. Somali songs are usually the product of collaboration between lyricists (midho), songwriters (laxan) and singers (codka or "voice"). Balwo is a Somali musical style centered on love themes that is popular in Djibouti.[152]

Traditional Afar music resembles the folk music of other parts of the Horn of Africa such as Ethiopia; it also contains elements of Arabic music. The history of Djibouti is recorded in the poetry and songs of its nomadic people, and goes back thousands of years to a time when the peoples of Djibouti traded hides and skins for the perfumes and spices of ancient Egypt, India and China. Afar oral literature is also quite musical. It comes in many varieties, including songs for weddings, war, praise and boasting.[153]

Literature

Djibouti has a long tradition of poetry. Several well-developed Somali forms of verse include the gabay, jiifto, geeraar, wiglo, 'buraanbur, beercade, afarey and guuraw. The gabay (epic poem) has the most complex length and meter, often exceeding 100 lines. It is considered the mark of poetic attainment when a young poet is able to compose such verse, and is regarded as the height of poetry. Groups of memorizers and reciters (hafidayaal) traditionally propagated the well-developed art form. Poems revolve around several main themes, including baroorodiiq (elegy), amaan (praise), jacayl (romance), guhaadin (diatribe), digasho (gloating) and guubaabo (guidance). The baroorodiiq is composed to commemorate the death of a prominent poet or figure.[154] The Afar are familiar with the ginnili, a kind of warrior-poet and diviner, and have a rich oral tradition of folk stories. They also have an extensive repertoire of battle songs.[155]

Additionally, Djibouti has a long tradition of Islamic literature. Among the most prominent historical works is the medieval Futuh Al-Habash by Shihāb al-Dīn, which chronicles the

Sport

Football is the most popular sport amongst Djiboutians. The country became a member of

Recently, the World Archery Federation has helped to implement the Djibouti Archery Federation, and an international archery training center is being created in Arta to support archery development in East Africa and Red Sea area.[citation needed]

Cuisine

See also

- Index of Djibouti-related articles

- Outline of Djibouti

- Religion in Djibouti

- Christianity in Djibouti

- Protestant Church of Djibouti

- Catholic Church in Djibouti

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Djibouti". The World Factbook. CIA. 5 February 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Democracy Index 2020". Economist Intelligence Unit. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "The world's enduring dictators Archived 9 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine". CBS News. May 16, 2011.

- S2CID 216340612.

- ^ "Djibouti". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Djibouti)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Mylonas, Harris. "De Facto States Unbound – PONARS Eurasia". PONARS Eurasia. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- OCLC 811620848.

- ^ ISBN 0903274051.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 383.

- ^ ISBN 1857431162.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 950.

- ^ "Today in Djibouti History". Historyorb.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "United Nations member states". United Nations. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-19-175139-4. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.)

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help - ^ Boujrada, Zineb (2 March 2018). "How Djibouti Got Its Unique Name". The Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Countries Of The World That Are Named After Legendary Figures". Worldatlas. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-295-4.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ISBN 978-0759104662. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ISBN 978-3447051750. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ISBN 978-1134403035. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ISBN 9783937248004. Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ISBN 978-1136755521. Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ISBN 978-0875862569

- ISBN 9780141929347

- ^ Breasted, John Henry (1906–1907), Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, collected, edited, and translated, with Commentary, vol. 1, University of Chicago Press, pp. 246–295

- ^ ISBN 0810843447

- ISBN 9780852552803. Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ISBN 9780810874572.

- ISBN 9780798303446.

- ISBN 978-1841623719. Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Image: The Travels of Al-Yaqubi". Image.prntsacr.com. Archived from the original (PNG) on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ISBN 9781118455074.

- ^ Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ a b Lewis, I.M. (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "A Country Study: Somalia from The Library of Congress". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ISBN 1598842048.

- ISBN 0415348102.

- ^ Africanus, Leo (1526). The History and Description of Africa. Hakluyt Society. pp. 51–54.

- ^ Northeast African Studies. Vol. 11. African Studies Center, Michigan State University. 1989. p. 115. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ISBN 9004082654. Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ISBN 0852552807. Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- doi:10.3406/ethio.1987.931. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Tiya - Prehistoric site". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ISBN 4879749761. Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "FRENCH SOMALI COAST 1708 – 1946 FRENCH SOMALI COAST | Awdalpress.com". Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013. FRENCH SOMALI COAST Timeline

- from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Tracer des frontières à Djibouti". djibouti.frontafrique.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Adolphe, Martens; Challamel, Augustin; C, Luzac (1899). Le Regime de Protectorats. Bruxelles: Institut Colonial Internationale. p. 383.

- ^ Simon, Imbert-Vier (2011). Trace des frontiere a Djibouti. Paris: Khartala. p. 128.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 383.

- ^ "Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 414.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 86.

- ^ "Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 950.

- ^ Imbert-Vier 2008, pp. 226–29.

- ^ Ebsworth 1953, p. 564.

- ^ ISBN 0472068989

- ^ Africa Research, Ltd (1966). Africa Research Bulletin, Volume 3. Blackwell. p. 597. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d Newsweek, Volume 81, (Newsweek: 1973), p.254.

- ^ a b American Universities Field Staff (1968) Northeast Africa series, Volume 15, Issue 1, p. 3.

- ^ a b Alvin J. Cottrell, Robert Michael Burrell, Georgetown University. Center for Strategic and International Studies, The Indian Ocean: its political, economic, and military importance, (Praeger: 1972), p.166.

- ^ "French Envoy in Somalia Held by Anti-Paris Group". The New York Times. 25 March 1975. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Gonidec, Pierre François. African Politics. The Hague: Matinus Nijhoff, 1981. p. 272

- ^ Légion-Étrangère. Légion-Étrangère. 2000. p. 2. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African history, (CRC Press: 2005), p.360.

- ISBN 0-19-829645-2

- ^ JSTOR 43660335.

- ^ "Djibouti President Guelleh wins election with 98%, provisional results". Africanews. n.d. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Djibouti's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 2010" (PDF). Constitute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Constitution de la République de Djibouti" (in French). Agence Djiboutienne d'Information. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Djibouti". Freedom House. 17 January 2012. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ a b "DJIBOUTI: Guelleh sworn in for second presidential term". IRIN Africa. 9 May 2005. Archived from the original on 29 November 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Djibouti validates presidential election". Middle East Online. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ "Sudan: President Al-Bashir Congratulates Djibouti President On His Re-Election". Sudan News Agency. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ "Joint statement of the international observer missions of the Djibouti presidential elections held on April 08, 2011". Intergovernmental Authority on Development. 10 April 2011. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

In view of the foregoing, the international mission found that the election of 8 April 2011 was peaceful, calm, fair, transparent and took place in dignity. It declares that the election was free and democratic.

- ^ "M. Abdoulkader Kamil Mohamed, grand commis de l'Etat et nouveau Premier ministre djiboutien". Adjib. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ "Djibouti government reaches deal to bring opposition into parliament". Goobjoog. 30 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ISBN 978-981-4713-03-0.access-date=28 March 2024

- ^ The Rise and Fall of the Somalia Airforce: A Diary Reflection Archived 26 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Somalia: UN Envoy Says Inauguration of New Parliament in Somalia 'Historic Moment'". Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Mohamed, Mahmoud (17 September 2012). "Presidential inauguration ushers in new era for Somalia". Sabahi. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ISBN 978-1136636967. Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Anthony Clayton, 'France, Soldiers, and Africa,' Brassey's, 1988, 388.

- ^ "Djibouti Is Hot". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Jacobs, Andrew; Perlez, Jane (25 February 2017). "U.S. Wary of Its New Neighbor in Djibouti: A Chinese Naval Base". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Djibouti, Foreign Military Bases on the Horn of Africa; Who is there? What are they up to?". 2 January 2019. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Styan, David (April 2013). "Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn's Strategic Hub". Chatham House. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Chandran, Nyshka (27 June 2018). "China increases defense ties with Africa". www.cnbc.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ State, US Department of (11 March 2020). "Country Report on Human Rights Practices 2019 – Djibouti". state.gov. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- .

- ^ Geothermal Resources Council (1985). 1985 International Symposium on Geothermal Energy, Volume 9, Part 1. p. 175.

- ^ a b Highest Mountains in Djibouti Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. geonames.org

- ^ "Eritrean coastal desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ a b "Weatherbase : Djibouti". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Le Pèlerin du Day". World Food Programme. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Djibouti". Living National Treasures. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ISBN 978-2-88032-977-8. Archivedfrom the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-2-8317-0021-2. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "Ethiopia signs Djibouti railway deal with China". Reuters. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Port Development and Competition in East and Southern Africa: Prospects and challenges (PDF). Transport Global Practice. Vol. 2: Country and Port Fact Sheets and Projections. World Bank Group. 2018. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bansal, Ridhima (23 September 2011). "Current Development Projects and Future Opportunities in Djibouti". Association of African Entrepreneurs. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Euromoney Country Risk". Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC. Archived from the original on 30 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "Djibouti, China Sign 64 mln USD Agreement to Facilitate Salt Export". Xinhua News Agency. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Djibouti banking boom attracts foreign investors". Reuters. 23 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Le système informel de transferts de fonds et le mécanisme automatique du Currency Board : complémentarité ou antagonisme ? Le cas des transferts des hawalas à Djibouti Archived 24 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. univ-orleans.fr

- ^ "Bridge of the Horns, Cities of Light: Will They Ever Actually Be Built?". The Basement Geographer. WordPress. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Phase I of Yemen and Djibouti Causeway delayed". Steelguru.com. 22 June 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Africa News: The China Merchants in Djibouti: from the maritime to the digital silk roads (by Thierry Pairault)". Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Harry G. Broadman "Afrika's Silk Road" (2007), pp 59.

- ^ Marcus Hernig: Die Renaissance der Seidenstraße (2018) pp 112.

- ^ Diego Pautasso "The role of Africa in the New Maritime Silk Road" In: Brazilian Journal of African Studies, v.1, n.2, Jul./Dec. 2016 | p.118-130.

- ^ David Styan "Djibouti and Small State Agency in the Maritime Silk Road: The Domestic and International Foundations" (2020).

- ^ "Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments". CIA. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Movie theaters in Djibouti, Djibouti". Cinema Treasures. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Djibouti media guide". BBC News. 20 December 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "African Nation of Djibouti banks on Chinese tourists". South China Morning Post. 17 April 2017. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Ethiosport launch of the train to Djibouti". ethiosports.com. 1 January 2018. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Things to do in Djibouti". onceinalifetimejourney. 14 March 2018. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Diversification key to expansion of Djibouti's energy sector". Oxford Business Group. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Djibouti Population". World Bank. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Somalia: Information on the Issa and the Issaq". Refworld. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ISBN 978-1740594622

- ^ DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE, INTELLIGENCE MEMORANDUM (1967). "French Somaliland" (PDF). Intelligence Memorandum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017.

- ^ USA (9 August 2012). "Religious Identity Among Muslims | Pew Research Center". Pewforum.org. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2006). "The Afro-Asiatic Languages: Classification and Reference List" (PDF). p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Cutbill, Catherine C.; Schraeder, Peter J. (22 August 2019). "Djibouti: Language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Djibouti – Languages". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "Islamic World". Nations Online. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 September 2013

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, "Djibouti: Situation and treatment of Christians, including instances of discrimination or violence; effectiveness of recourse available in cases of mistreatment; problems that a Muslim can face if he or she converts to Christianity or marries a Christian (2000–2009)", 5 August 2009". Unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Cheney, David M. "Diocese of Djibouti". Catholic-hierarchy.org. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ "Djibouti: Regions, Major Cities & Towns – Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Republic of Djibouti: Humanitarian Country Profile". IRIN. February 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "The State of the World's Midwifery". United Nations Population Fund. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ "Prevalence of FGM". Who.int. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- .

- ISBN 1555875785.

- ^ a b "DJIBOUTI: Women fight mutilation". IRIN. 12 July 2005. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ISBN 1563081318.

- ^ Eric Werker; Amrita Ahuja; Brian Wendell. "Male Circumcision and AIDS: The Macroeconomic Impact of a Health Crisis" (PDF). NEUDC 2007 Papers :: Northeast Universities Development Consortium Conference: Center for International Development at Harvard Un. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Hare, Harry (2007) ICT in Education in Djibouti Archived 16 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, World Bank

- ^ Djibouti Assistance to Education Evaluation Archived 12 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. USAID (April 2009)

- ISBN 978-0756698591. Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "Image of Djibouti women in head-dresses". discoverfrance.net. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ISBN 9780313313332

- ^ "Djibouti – Culture Overview". Expedition Earth. Archived from the original on 27 February 2004. Retrieved 28 September 2005. – Website no longer exists; link is to Internet Archive

- ISBN 9780313313332

- ISBN 9781741044362

- ISBN 9780972317269. Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ISBN 9781425977061

Sources

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook (2024 ed.).

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook (2024 ed.). - Ebsworth, W. A. (1953). "Jibouti and Madagascar in the 1939–45 War". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. 98 (592): 564–68. .

- Imbert-Vier, Simon (2008). Frontières et limites à Djibouti durant la période coloniale (1884–1977) (PhD thesis). Université de Provence–Aix-Marseille I.

External links

- Government

- "Site Officiel de la République de Djibouti" [Official website of the Republic of Djibouti] (in French). Government of Djibouti.

- "Office National de Tourisme de Djibouti". National Official of Tourism of Djibouti. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- Profile

- Djibouti. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Djibouti profile from the BBC News.

- Djibouti web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Djibouti at Curlie

- Others