Irish Catholic Martyrs

| Irish Catholic Martyrs | |

|---|---|

Roman Catholic Church | |

| Beatified | 3 were beatified on 15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI 1 was beatified on 22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II 18 were beatified on 27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | 1 (Oliver Plunkett) was canonized on 12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI |

| Feast | 20 June, various for individual martyrs |

Irish Catholic Martyrs (

The more than three century-long

According to historian and

The 1975 canonization of Archbishop Oliver Plunkett, who was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on 1 July 1681, as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales raised considerable public interest in other Irishmen and Irishwomen who had similarly died for their Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries. On 22 September 1992 Pope John Paul II beatified an additional 17 martyrs and assigned June 20, the anniversary of the 1584 martyrdom of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley, as their feast day.[4] Many other causes for Roman Catholic Martyrdom and possible Sainthood, however, remain under active investigation.

History

Henry VIII

Religious persecution of Catholics in Ireland began under

According to D.P. Conyngham, "Though the faithful underwent fearful persecutions toward the latter part of the reign of Henry, few publicly suffered martyrdom. Numbers of the monks and religious were killed at their expulsion from their houses, but the King's adhesion to many articles of Catholicity made it too hazardous for his agents in Ireland to resort to the stake or the gibbet. In fact, Henry burned at the same stake

Meanwhile, the King and

On c.30 July 1535,

According to Philip O'Sullivan Beare, "[John Travers] wrote something against the English heresy, in which he maintained the jurisdiction and authority of the Pope. Being arraigned for this before the King's court, and questioned by the judge on the matter, he fearlessly replied - 'With these fingers', said he, holding out the thumb, index, and middle fingers, of his right hand, 'those were written by me, and for this deed in so good and holy a cause I neither am nor will be sorry.' There upon being condemned to death, amongst other punishments inflicted, that glorious hand was cut off by the executioner and thrown into the fire and burnt, except the three sacred fingers by which he had effected those writings, and which the flames, however piled on and stirred up, could not consume."[12]

In 1536,

When the

Elizabeth I

Even though she continued the plantation of Ireland with English settlers, the persecution of Catholics ceased after the accession of the Catholic

From the early years of her reign, pressure was put on all her subjects to conform to the "

In 1563 the

In Ireland the

The ongoing religious persecution also became highly significant as the primary cause of the Nine Years War, which similarly sought to replace Queen Elizabeth with a High King from the House of Habsburg. The war formally began when Red Hugh O'Donnell expelled English High Sheriff of Donegal Humphrey Willis, but not before Red Hugh listed his reasons for taking up arms against the House of Tudor and alluded in particular to the recent torture and executions of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley and Bishop Patrick O'Hely. According to Philip O'Sullivan Beare, "Being surrounded there [Willis] surrendered to Roe by whom he was dismissed in safety with an injunction to remember his words, that the Queen and her officers were dealing unjustly with the Irish; that the Catholic religion was contaminated by impiety; that holy bishops and priests were inhumanely and barbarously tortured; that Catholic noblemen were cruelly imprisoned and ruined; that wrong was deemed right; that he himself had been treacherously and perfidiously kidnapped; and that for these reasons he would neither give tribute or allegiance to the English."[18]

Beatified Martyrs include:

- Patrick O'Hely (Irish: Pádraig Ó hÉilí), Franciscan Friar from Creevelea Abbey (Irish: an Mainistir na Craoibhe Léithe) at Dromahair, County Leitrim, and Bishop of Mayo. Executed by hanging outside the walls of Kilmallock 13 August 1579

- Conn O'Rourke (Lord of Breifne, executed with Bishop O'Hely by hanging outside the walls of Kilmallock, 13 August 1579

- 5 Wexford Martyrs, sailors engaged in smuggling priests, laity, and banned Catholic literature in and out of Ireland, hanged, drawn and quartered in Wexford, 5 July 1581

- Margaret Ball, former Lady Mayoress of Dublin, died as a prisoner of conscience in Dublin Castle for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, 1584[19]

- Rheims University. Arrested in 1583 after ordination abroad, being smuggled back into Ireland, and following a secret underground ministry. Tortured at Dublin Castle by being put to the "hot boots" for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy and then hanged using a noose woven from willow branches outside the walls of Dublin, 20 June 1584. Secretly buried afterwards in St Kevin's Churchyard

- Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh (Maurice MacKenraghty), Diocesan priest and former military chaplain during the Second Desmond Rebellion. Voluntarily surrendered himself, similarly to St Maximilian Kolbe, intending to die in the place of a condemned Recusant named Victor White. Executed for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy by hanging and posthumous beheading at Clonmel, 30 April 1585

- Battle of Kinsale and the 11-day Siege of Dunboy. Officially hanged for high treason, but in reality for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, outside the walls of his native Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[20]

Servants of God include:

- Edmund Daniel, SJ, 25 October 1572 in Cork

- Teige O'Daly, OFM, about March 1578 in Limerick

- Donal O'Neylan, OFM, 28 March 1580 in Youghal, Cork

- Cistercian Abbot of Boyle, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- Eoin O'Mulkern, OPraem, Abbot of Holy Trinity Abbey upon Lough Key, hanged 21 November 1580 outside the walls of Dublin

- David, John Sutton and Robert Scurlock, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Maurice, Thomas, and Christopher Eustace, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- William Wogan and Robert Fitzgerald, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Felim O'Hara, OFM, 1 May 1582 in Moyne, Cork

- Walter Eustace, layman, 14 June 1583 in Dublin

- Richard Creagh (Irish: Risteard Craobhach) (born 1523), Archbishop of Armagh, December 1586 as a prisoner of conscience in the Tower of London, England

King James I

According to D.P. Conyngham, "It was fondly hoped by the Catholics of Ireland that the accession of

A Royal edict issued on 4 July 1605 announced that Elizabethan era Recusancy laws were to be rigorously enforced and added, "It hath seemed proper to us to proclaim, and we hereby make it known to our subjects in Ireland, that no toleration shall ever be granted by us. This we do for the purpose of cutting off all hope that any other religion shall be allowed - save that which is consonant to the laws and statutes of this realm."[22]

Beatified Martyrs include:

- Polycarp of Smyrna, in his eighties, Bishop Ó Duibheannaigh was hanged, drawn and quartered outside Dublin City, 11 February 1612. Secretly buried afterwards at St James Churchyard

- spiritual director to Aodh Mór Ó Néill, hanged, drawn and quartered outside Dublin City, 11 February 1612. Secretly buried afterwards at St James Churchyard

- Francis Taylor, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, died as a prisoner of conscience in Dublin Castle for refusing to say the Oath of Supremacy, 1621

Servants of God include:

- Brian O'Carolan, priest, 24 March 1606 near Trim, County Meath

- John Burke, layman, 20 December 1606 in Limerick

- Donough MacCready, priest, before 5 August 1608 in Coleraine, County Londonderry

King Charles I

According to historian D.P. Conyngham, "Ireland was torn by contending factions, and was oppressed by two belligerents during the reign of Charles. The Catholics took up arms in defense of themselves, their religion, and their King. Charles, with the proverbial fickleness of the Stuarts, when pressed by the Puritans, persecuted the Irish, while he encouraged them when he hoped their loyalty and devotion would be the means of establishing his royal prerogative. It is ever thus with Ireland... For eight years Ireland was the theatre of the most desolating war and implacable persecution."[23]

Beatified Martyrs of the era include:

- Fr. Peter O'Higgins, Dominican Order, hanged outside the walls of Dublin at St Stephen's Green, on 24 March 1642[24][25][26]

Servants of God include:

- George Halley (born 1622), OCD, 15 August 1642 in Siddan, County Meath

The Commonwealth and Protectorate of England

On 24 October 1644, the Puritan-controlled

According to historian D.P. Conyngham, "It is impossible to estimate the number of Catholics slain the ten years from 1642 to 1652. Three Bishops and more than 300 priests were put to death for their faith. Thousands of men, women, and children were sold as slaves for the West Indies; Sir W. Petty mentions that 6,000 boys and women were thus sold. A letter written in 1656, quoted by Lingard, puts the number at 60,000; as late as 1666 there were 12,000 Irish slaves scattered among the West Indian islands. Forty thousand Irish fled to the Continent, and 20,000 took shelter in the Hebrides or other Scottish islands. In 1641, the population of Ireland was 1,466,000, of whom 1,240,000 were Catholics. In 1659 the population was reduced to 500,091, so that very nearly 1,000,000 must have perished or been driven into exile in the space of eighteen years. In comparison with the population of both periods, this was even worse than the famine extermination of our own days."[28]

After taking the island in 1653, the

Officially Beatified Martyrs of the era include:

- Fr. Theobald Stapleton, (Irish: Teabóid Gálldubh), slain during the Sack of Cashel, 15 September 1647.[30]

- Bishop Terence O'Brien of Emly, Dominican Order, hanged at Gallows Green by order of New Model Army General Henry Ireton following the Siege of Limerick, 31 October 1651

- John Kearney (1619-1653) was born in Cashel, County Tipperary and joined the Franciscans at the Kilkenny friary. After his novitiate, he went to Leuven in Belgium and was ordained in Brussels in 1642. Returned to Ireland, he taught in Cashel and Waterford, and was much admired for his preaching. In 1650 he became erenagh of Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, he was arrested by the New Model Army while continuing to exercise an illegal and underground priestly ministry throughout the valley of the River Suir and executed by hanging at Clonmel, County Tipperary on 21 March 1653. He lies buried in the chapter hall of the suppressed friary of Cashel.[31][32][32]

- Fr. 12 May 1654

Servants of God include:

Sack of Cashel

Martyred by the Protestant and Parliamentarian soldiers under the command of the Lord President of Munster, Murchadh na dTóiteán, during the Sack of Cashel

- Edward Stapleton, priest, 13 September 1647,

- Thomas Morissey, priest, 13 September 1647 Sack of Cashel, County Tipperary

- Richard Barry, OP, 13 September 1647, Sack of Cashel, County Tipperary

- Richard Butler and James Saul, OFM, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- William Boyton, SJ, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Elizabeth Kearney (mother of Blessed John Kearney) and Margaret (surname unrecorded), laywomen, on 13 September 1647

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

- Laurence and Bernard O'Ferrall, OP, between February–March 1649 in Longford

- John Bathe, SJ and Thomas Bathe, priest, 11 September 1649, following the Siege of Drogheda, County Louth

- Peter Taafe, OSA,11 September 1649, following the Siege of Drogheda, County Louth

- Dominic Dillon and Richard Oveton, OP, 11 September 1649, following the Siege of Drogheda, County Louth

- Conor MacCarthy, priest, 5 June 1653 in Killarney, County Kerry

- Francis O'Sullivan, OFM, 23 June 1653, Scariff Island, County Kerry

- Thaddeus Moriarty, OP, 15 October 1653 in Killarney, County Kerry

- Donal Breen and James Murphy, priests, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- Luke Bergin, OP, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- John Tobin (born 1620), OFMCap, 6 March 1656 in Waterford

Charles II

During the Stuart Restoration, the Crown's treatment of Catholics was more lenient than usual, owing to the sympathy of the king. For this reason, Catholic worship generally moved from the Mass rocks to thatched "Mass houses" (Irish: Cábán an Aifrinn, lit. ‘Mass Cabin’). Writing in 1668, Janvin de Rochefort commented, "Even in Dublin more than twenty houses where Mass is secretly said, and in about a thousand places, subterranean vaults and retired spots in the woods".[33]

This changed radically, however, due to the Popish Plot, a conspiracy theory concocted by Titus Oates and Lord Shaftesbury, who claimed that a plot existed to assassinate the King and massacre all the Protestants of the British Isles. Between 1678 and 1681, the attention of the public was riveted upon a series of anti-Catholic show trials that resulted in 22 executions at Tyburn.

As persecution of Catholics heated up in reaction to the Titus Oates plot, a priest with the

Irish victims of the Titus Oates witch hunt included:

- Peter Talbot, Archbishop of Dublin (died imprisoned in Dublin Castle, November 1680)

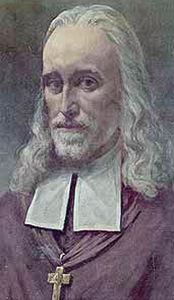

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, executed at Tyburn 1 July 1681

Age of the Whig oligarchy

Despite their exposure and public disgrace in 1681, the anti-Catholic

As the Whig-controlled Parliament of Ireland passed the

During the

A 1709 Penal Act demanded that Catholic priests take the Oath of Abjuration, and recognise the Protestant Queen Anne as Supreme Head of the Church within all her dominions and declare that Catholic doctrine regarding Transubstantiation to be "base and idolatrous".[38]

Priests who refused to take the oath abjuring the Catholic faith were arrested and executed. This activity, along with the compulsory deportation of other priests who did not conform, was a documented attempt to cause the Catholic clergy to die out in Ireland within a generation. Priests had to register with the local magistrates to be allowed to preach, and most did so. Bishops were not permitted to register.[39]

In 1713, the Irish House of Commons declared that "prosecution and informing against Papists was an honourable service", which revived the Elizabethan era profession of the priest hunter,[40] the most infamous of whom remains John O'Mullowny, nicknamed (lang-ga|Seán na Sagart}}), of the Partry Mountains in County Mayo.[41] The reward rates for capture varied from £50–100 for a bishop, to £10–20 for the capture of an unregistered priest: substantial amounts of money at the time.[39]

While being interviewed by Tadhg Ó Murchú of the

- James Dowdall (born 1626), OFMCap, 20 February 1710 in London, England

- Fr. Nicholas Sheehy, Diocesan priest, hanged at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 15 March 1766

First French Republic

- Fr. First French Republic and secretly continuing his priestly ministry in nonviolent resistance to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and during the Reign of Terror, guillotined at Bordeaux, 20 July 1794

Investigations

The Irish Martyrs suffered over several reigns and even at the hands of both sides during

Detailed accounts were also written and published by

After the successful fight that was eventually spearheaded by

The first Apostolic Process under Canon Law began in Dublin in 1904, after which the findings were submitted to the Holy See.

In the 12 February 1915 Apostolic decree In Hibernia, heroum nutrice, Pope Benedict XV formally authorized the formal introduction of additional Causes for Roman Catholic Sainthood.[45]

During a further Apostolic Process held at Dublin between 1917 and 1930 and against the backdrop of the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, the evidence surrounding 260 alleged cases of Roman Catholic martyrdom were further investigated, after which the findings were again submitted to the Holy See.[44]

Thus far, the only Martyr to complete the process was

Other causes have also been formally recognized.

The 6 Irish Martyrs of England and Wales

Canonized Martyrs

12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI.

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, 1 July 1681 at Tyburn, London; beatified 1920

Beatified Martyrs

15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI.

- Patrick Salmon, laymen, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Cornelius (Irish: Seán Conchobhar Ó Mathghamhna), Jesuit priest, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Roche, layman, 30 August 1588 at Tyburn, England

22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II.

- Charles Mahoney (alias Meehan), Franciscan, 21 August 1679, Ruthin, Wales

The 17 Blessed Irish Martyrs

27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II.

- Patrick O'Hely (Irish: Pádraig Ó hÉilí), Franciscan Bishop of Mayo, betrayed to Lord President of Munster Sir William Drury by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock 13 August 1579

- Conn O'Rourke (Irish: Conn Ó Ruairc), Franciscan Friar, betrayed to the priest hunters by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock, 13 August 1579

- Wexford Martyrs, 5 July 1581: Matthew Lambert, Robert Myler, Edward Cheevers, Patrick Cavanagh (Irish: Pádraigh Caomhánach), John O'Lahy, and one other unknown individual

- Margaret Ball, former Lady Mayoress of Dublin, died 1584, as a prisoner of conscience inside Dublin Castle[19]

- military tribunal and hanged at Lower Baggot Street, then outside the walls of Dublin, 20 June 1584

- Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh (Maurice MacKenraghty), military chaplain to the Rebel Earl of Desmond, executed at Clonmel, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, 30 April 1585

- Dominic Collins, Jesuit lay brother captured by the Tudor Army following the Siege of Dunboy and executed without trial at Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[20]

- Concobhar Ó Duibheannaigh (Conor O'Devany), Franciscan Bishop of Down & Connor, 11 February 1612

- Patrick O'Loughran, priest from County Tyrone and former spiritual director to Aodh Mór Ó Néill, 11 February 1612

- Francis Taylor, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, died as a prisoner of conscience inside Dublin Castle, 1621

- Irish rebellion of 1641, at St Stephen's Green, then outside the walls of Dublin, on 24 March 1642[24][46][47]

- Parliamentary Army of Lord Inchiquin (Irish: Murchadh na dTóiteán) during the Sack of Cashel, 15 September 1647. Fr. Stapleton is said to have blessed his attackers with holy water moments before his death.[30]

- Limerick City, 31 October 1651

- John Kearney, Franciscan Prior of Cashel, hanged at Clonmel, officially for high treason, but in reality for covertly continuing his priestly ministry throughout the valley of the River Suir in nonviolent resistance to the Commonwealth of England's recent decree banishing of all Catholic priests, 21 March 1653[31][32]

- 12 May 1654

The 42 Martyred Irish Servants of God

A group of 42 Irish martyrs have been selected for canonisation. This group is composed mostly of priests, both secular and religious as well as several lay men and two lay women. These martyrs have not yet been beatified.

- Edmund Daniel, SJ, 25 October 1572 in Cork

- Teige O'Daly, OFM, about March 1578 in Limerick

- Donal O'Neylan, OFM, 28 March 1580 in Youghal, Cork

- Cistercian Abbot of Boyle, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- Eoin O'Mulkern, OPraem, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- David, John Sutton and Robert Scurlock, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Maurice, Thomas, and Christopher Eustace, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- William Wogan and Robert Fitzgerald, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Felim O'Hara, OFM, 1 May 1582 in Moyne, Cork

- Walter Eustace, layman, 14 June 1583 in Dublin

- Richard Creagh (Irish: Risteard Craobhach) (born 1523), Archbishop of Armagh, December 1586 as a prisoner of conscience in the Tower of London, England

- Brian O'Carolan, priest, 24 March 1606 near Trim, Meath

- John Burke, layman, 20 December 1606 in Limerick

- Donough MacCready, priest, before 5 August 1608 in Coleraine, Northern Ireland

- George Halley (born 1622), OCD, 15 August 1642 in Siddan, Meath

- Theobald and Edward Stapleton, priests, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Thomas Morissey, priest, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Richard Barry, OP, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Richard Butler and James Saul, OFM, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- William Boyton, SJ, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Elizabeth Kearney (mother of Blessed John Kearney) and Margaret (surname unrecorded), laywomen, martyred by the Protestant soldiers under the command of the Lord President of Munster, Murchadh na dTóiteán, during the Sack of Cashel on 13 September 1647

- John Bathe, SJ and Thomas Bathe, priest, 11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Peter Taafe, OSA,11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Dominic Dillon and Richard Oveton, OP, 11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Laurence and Bernard O'Ferrall, OP, between February–March 1649 in Longford

- Conor MacCarthy, priest, 5 June 1653 in Killarney, Kerry

- Francis O'Sullivan, OFM, 23 June 1653 on Scarrrif Island, Kerry

- Thaddeus Moriarty, OP, 15 October 1653 in Killarney, Kerry

- Donal Breen and James Murphy, priests, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- Luke Bergin, OP, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

Fr. John O'Neill and the Bonane pilgrimage shrine

Even though the name of Fr. John O'Neill does not appear on the 1992 list of Catholic priests known to have served locally,

This region of County Kerry had extremely rough terrain, few well-constructed roads, and was very difficult to travel to from other regions of Ireland without being robbed or even murdered by

Even though this makes of Father John O'Neill's martyrdom plausible, but difficult to definitively confirm, Inse an tSagairt, despite being remote and difficult to access until well into the 20th-century, remained a place of reverence and devotion. For example, Fr. Eugene Daly's interest in the site began during his childhood, when his mother fell gravely ill and her life had been despaired of. As a deeply religious woman, however, Mrs. Daly requested that a drink of water be brought to her from Inse an tSagairt, which resulted in what was locally seen as a miraculous cure.[56] Both Fr. O'Neill's martyrdom and the cure of Mrs. Daly have been commemorated in locally composed Irish poetry.[57]

Since a hiking path was built there by the Coillte agency of the Irish State in 1981 at Fr. Daly's insistence,[58] Inse an tSagairt has been a site of Christian pilgrimage and is still used by the local parish for an open air Annual Commemorative Mass every June. There is also a memorial plaque next to the altar in honour of Fr. John O'Neill.[50][52][59][60] Other local Mass rock locations were an Alhóir, near the summit of Mount Esker, An Seana-Shéipeil at Garrymore, and Faill-a Shéipéil at Gearha.[61]

Legacy

Various parish churches have also been dedicated since 1992 to the Irish Catholic Martyrs, including:

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine, Letterkenny,[19] County Donegal

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballycane, Naas[62] County Kildare

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Cromwell, Otago, New Zealand.

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Mallee Border Parish, Lameroo, South Australia, Australia

- Chapel of the Irish Martyrs, Pontificio Collegio Irlandese, Pontifical Irish College, Rome, Italy.

Furthermore,

See also

- English Reformation

- List of Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation

- Act of Supremacy.

References

- ^ a b Barry, Patrick, "The Penal Laws", L'Osservatore Romano, p.8, 30 November 1987

- ^ Marcus Tanner (2004), The Last of the Celts, Yale University Press. Pages 227-228.

- ^ Seamus MacManus (1921), The Story of the Irish Race, Barnes & Noble. pp. 462-463.

- ^ CREAZIONE DI VENTUNO NUOVI BEATI: OMELIA DI GIOVANNI PAOLO II, Piazza San Pietro - Domenica, 27 settembre 1992.

- ^ a b c "The Irish Martyrs", Irish Jesuits, sacredspace.ie; accessed 16 December 2015.

- ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Irish Confessors and Martyrs".

- Google Books).

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 26.

- Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, pp. 687-699.

- ^ "Martyrs of England and Wales" New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9 (1967), p. 322.

- Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, pp. 687-699.

- ^ Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1903), Chapters Towards a History of Ireland Under Elizabeth, pages 2-3.

- ^ "Martyrs of England and Wales" New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9 (1967), p. 322.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Pages 26-27.

- ^ L.P. Murray (1935), "The Franciscan Monasteries after the Dissolution", Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 8, No. 3 (1935), pp. 275-282.

- ^ "The Reign of Elizabeth I" Archived 2017-05-09 at the Wayback Machine by J.P. Sommerville, University of Wisconsin.

- ^ Cusack, Margaret Anne, An Illustrated History of Ireland, libraryireland.com; accessed 11 July 2015.

- ^ Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1903), Chapters Towards a History of Ireland Under Elizabeth, page 68.

- ^ a b c ""The Irish Martyrs", The Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine". Archived from the original on 2013-09-24. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ a b "Archives".

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 104.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Pages 104-105.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 137.

- ^ a b "Peter O'Higgins OP". Newbridge College.

- ^ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Pages 148–156.

- ^ Clavin, Terry (October 2009). "Higgins, Peter". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography (online ed.). Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 138.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 138.

- ^ Nugent, Tony (2013). Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland. Liffey Press. Pages 51-52, 148.

- ^ a b "Stapleton, Theobald ('Teabóid Gálldubh') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 2022-05-20.

- ^ a b "Franciscan Saints & Blessed". Archived from the original on 2014-02-04.

- ^ a b c Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Pages 165–175.

- ^ Nugent 2013, p. 143.

- ^ Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, pages 80–81.

- ^ Seamus MacManus (1921), The Story of the Irish Race, Barnes & Noble. pp. 454-469.

- ^ Erika Papp Faber (2005), Our Mother's Tears: Ten Weeping Madonnas in Historic Hungary, Academy of the Immaculate. New Bedford, Massachusetts. pp. 44-55, 88-89.

- ^ Hungarian bishop to present 'Irish Madonna' by Patsy McGarry, The Irish Times, Friday October 10, 2003.

- ^ D. P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kennedy & Sons, New York City. Page 240-241.

- ^ a b MacManus, Seumas (1921). The Story of the Irish Race: A Popular History of Ireland. New York: The Irish Publishing Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, The Liffey Press. Page 48.

- ^ Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, pages 40-47.

- ^ Seamus MacManus (1921), The Story of the Irish Race, Barnes & Noble. p. 463.

- Cork City. pp. 40-45.

- ^ a b Corish & Millet 2005, p. 79.

- ^ Index ac status causarum beatificationis servorum dei et canonizationis beatorum (in Latin). Typis polyglottis vaticanis. January 1953. p. 56.

- ^ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Pages 148–156.

- ^ Clavin, Terry (October 2009). "Higgins, Peter". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography (online ed.). Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Terence Albert O'Brien. The Catholic Encyclopedia] Retrieved 28 September 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. pp. 68-70.

- ^ a b Nugent 2013, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. p. 19.

- ^ a b "History of Bonane - Inse an t-Sagairt". Bonane Heritage Park. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ "Inse an tSagairt". holywellscorkandkerry.com. Holy Wells of Cork & Kerry. 10 November 2017.

- ^ The Mass Rock at Inse an tSagairt.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. pp. 40-44.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. pp. 19-21, 86.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. pp. 110-113.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. p. 86.

- ^ "Inse an tSagairt". holywellscorkandkerry.com. Holy Wells of Cork & Kerry. 10 November 2017.

- ^ The Mass Rock at Inse an tSagairt.

- ^ Edited by Fr. John Shine (1992), Bonane: A Centenary Celebration, Printed by theLeinster Leader, Naas. pp. 19-21.

- ^ "Naas Parish website". Archived from the original on 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ^ Chì Mi / I See: Bàrdachd Dhòmhnaill Iain Dhonnchaidh / The Poetry of Donald John MacDonald, edited by Bill Innes. Acair, Stornoway, 2021. Pages 346-347.

Sources

- Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin.

- New Catholic Dictionary: Irish Martyrs

- O'Reilly, Myles (1880). Lives of the Irish Martyrs and Confessors. New York: James Sheehy. OCLC 173466082.