Military history of France

|

| French Army lists |

|---|

| Field armies in the First World War |

| Divisions in the First World War |

| Divisions in the Second World War |

| Regiments |

The military history of France encompasses an immense panorama of conflicts and struggles extending for more than 2,000 years across areas including modern France, Europe, and a variety of regions throughout the world.

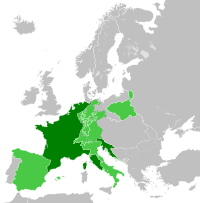

According to historian Niall Ferguson, France is the most successful military power in history. It participated in 50 of the 125 major European wars that have been fought since 1495; more than any other European state. The first major recorded wars in the territory of modern-day France itself revolved around the Gallo-Roman conflict that predominated from 60 BC to 50 BC. The Romans eventually emerged victorious through the campaigns of Julius Caesar. After the decline of the Roman Empire, a Germanic tribe known as the Franks took control of Gaul by defeating competing tribes. The "land of Francia", from which France gets its name, had high points of expansion under kings Clovis I and Charlemagne, who established the nucleus of the future French state. In the Middle Ages, rivalries with England prompted major conflicts such as the Norman Conquest and the Hundred Years' War. With an increasingly centralized monarchy, the first standing army since Roman times, and the use of artillery, France expelled the English from its territory and came out of the Middle Ages as the most powerful nation in Europe, only to lose that status to the Holy Roman Empire and Spain following defeat in the Italian Wars. The Wars of Religion crippled France in the late 16th century, but a major victory over Spain in the Thirty Years' War made France the most powerful nation on the continent once more. In parallel, France developed its first colonial empire in Asia, Africa, and in the Americas. Under Louis XIV France achieved military supremacy over its rivals, but escalating conflicts against increasingly powerful enemy coalitions checked French ambitions and left the kingdom bankrupt at the opening of the 18th century.

Resurgent French armies secured victories in dynastic conflicts against the

within France itself.Following defeat in the

Dominant themes

Historian Niall Ferguson argues that France is the most belligerent military power in history. It participated in 50 of the 125 major European wars fought since 1495; more than any other European state. It is followed by Austria which fought in 47 of them; Spain in 44; and England in 43. Out of the 169 most important world battles fought since 387BC, France has won 109, lost 49 and drawn 10.[2]

In the last few centuries, French strategic thinking has sometimes been driven by the need to attain or preserve the so-called "natural frontiers," which are the

Starting in the early 16th century, much of France's military efforts were dedicated to securing its overseas possessions and putting down dissent among both French colonists and native populations. French troops were spread all across its empire, primarily to deal with the local population. The French colonial empire ultimately disintegrated after the failed attempt to subdue Algerian nationalists in the late 1950s, a failure that led to the collapse of the

Early period

Around 390 BC, the Gallic

Around 125 BC, the south of France is conquered by the Romans who called this region Provincia Romana ("Roman Province"), which evolved into the name Provence in French.[10] Brennus' sack of Rome was still remembered by Romans, when Julius Caesar conquered the remainder of Gaul. Initially Caesar met with little Gallic resistance: the 60 or so tribes that made up Gaul were unable to unite and defeat the Roman army, something Caesar exploited by pitting one tribe against another. In 58 BC, Caesar defeated the Germanic tribe of the Suebi, which was led by Ariovistus. The following year he conquered the Belgian Gauls after claiming that they were conspiring against Rome. The string of victories continued in a naval triumph against the Veneti in 56 BC. In 53 BC, a united Gallic resistance movement under Vercingetorix emerged for the first time. Caesar laid siege to the fortified city of Avaricum (Bourges) and broke through the defenses after 25 days, with only 800 out of the 40,000 inhabitants managing to escape.[11] He then besieged Gergovia, Vercingetorix's home town, and suffered one of the worst defeats in his career when he had to retreat to suppress a revolt in another part of Gaul. After returning, Caesar surrounded Vercingetorix at Alesia in 52 BC. The townspeople were starved into submission and Caesar's unique defensive earthworks, protruding towards the city and away from it in order to stop a massive Gallic relief force,[12] eventually forced Vercingetorix to surrender. The Gallic Wars were over.

Following Clovis, territorial divisions in the Frankish domain sparked intense rivalry between the western part of the kingdom,

Under Charlemagne the Franks reached the height of their power. After campaigns against Lombards, Avars, Saxons, and Basques, the resulting Carolingian Empire stretched from the Pyrenees to Central Germany, from the North Sea to the Adriatic. In 800 the Pope made Charlemagne Emperor of the West in return for protection of the Church. The Carolingian Empire was a conscious effort to recreate a central administration modeled on that of the Roman Empire,[15] but the motivations behind military expansion differed. Charlemagne hoped to provide his nobles an incentive to fight by encouraging looting on campaign. Plunder and spoils of war were stronger temptations than imperial expansion, and several regions were invaded over and over in order to bolster the coffers of Frankish nobility.[16] Cavalry dominated the battlefields, and while the high costs associated with equipping horses and horse-riders helped limit their numbers, Carolingian armies maintained an average size of 20,000 during peacetime by recruiting infantry from imperial territories near theaters of operation, swelling to more with the levies called upon when at war.[17] The Empire lasted from 800 to 843, when, following Frankish tradition, it was split between the sons of Louis the Pious by the Treaty of Verdun.

Middle Ages

Military history during this period paralleled the rise and eventual fall of the armored

During the

In the 11th century, French knights wore knee-length

Improvements in armor over the centuries led to the establishment of

in 1429.Popular conceptions of the third and final phase of the Hundred Years War are often dominated by the exploits of

Equipment of medieval French sergeants was based on their property:[34]

| Property worth | Military equipment |

|---|---|

| L60+ | Hauberk, helmet, sword, knife, spear, and shield |

| L30+ | Gambeson, sword, knife, spear, and shield |

| L10+ | Helmet, sword, knife, spear, and shield |

| L10< | Bow, arrows, and knife |

Ancien Régime

The

After the Wars of Religion, France could do little to challenge the dominance of the Holy Roman Empire, although the empire itself faced several problems. From the east it was

The long reign of

Wars in this era consisted mostly of

The 18th century saw France remain the dominant power in Europe, but begin to falter largely because of internal problems. The country engaged in a long series of wars, such as the War of the Quadruple Alliance, the War of the Polish Succession, and the War of the Austrian Succession, but these conflicts gained France little. Meanwhile, Britain's power steadily increased, and a new force, Prussia, became a major threat. This change in the balance of power led to the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, when France and the Habsburgs forged an alliance after centuries of animosity.[43] This alliance proved less than effective in the Seven Years' War, but in the American Revolutionary War, the French helped inflict a major defeat on the British.

Revolutionary France

The French Revolution, true to its name, revolutionized nearly all aspects of French and European life. The powerful sociopolitical forces unleashed by a people seeking liberté, égalité, and fraternité made certain that even warfare was not spared this upheaval. 18th-century armies—with their rigid protocols, static operational strategy, unenthusiastic soldiers, and aristocratic officer classes—underwent massive remodeling as the French monarchy and nobility gave way to liberal assemblies obsessed with external threats. The fundamental shifts in warfare that occurred during the period have prompted scholars to identify the era as the beginning of "modern war".[44]

In 1791 the Legislative Assembly passed the "Drill-Book" legislation, implementing a series of infantry doctrines created by French theorists because of their defeat by the Prussians in the Seven Years' War.[45] The new developments hoped to exploit the intrinsic bravery of the French soldier, made even more powerful by the explosive nationalist forces of the Revolution. The changes also placed a faith on the ordinary soldier that would be completely unacceptable in earlier times; French troops were expected to harass the enemy and remain loyal enough to not desert, a benefit other Ancien Régime armies did not have. Following the declaration of war in 1792, an imposing array of enemies converging on French borders prompted the government in Paris to adopt radical measures. August 23, 1793, would become a historic day in military history; on that date the National Convention called a levée en masse, or mass conscription, for the first time in human history.[46] By summer of the following year, conscription made some 500,000 men available for service and the French began to deal blows to their European enemies.[47]

Armies during the Revolution became noticeably larger than their Holy Roman counterparts, and combined with the new enthusiasm of the troops, the tactical and strategic opportunities became profound. By 1797 the French had defeated the

Besides opening a flood of tactical and strategic opportunities, the Revolutionary Wars also laid the foundation for modern military theory. Later authors that wrote about "nations in arms" drew inspiration from the French Revolution, in which dire circumstances seemingly mobilized the entire French nation for war and incorporated nationalism into the fabric of military history.[49] Although the reality of war in the France of 1795 would be different from that in the France of 1915, conceptions and mentalities of war evolved significantly. Clausewitz correctly analyzed the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras to give posterity a thorough and complete theory of war that emphasized struggles between nations occurring everywhere, from the battlefield to the legislative assemblies, and to the very way that people think.[50] War now emerged as a vast panorama of physical and psychological forces heading for victory or defeat.

Napoleonic France

The

Napoleon inherited an army that was based on conscription and used huge masses of poorly trained troops, which could usually be readily replaced.

This large size came at a cost, as the logistics of feeding a huge army made them especially dependent on supplies. Most armies of the day relied on the supply-convoy system established during the Thirty Years' War by

Napoleon's biggest influence in the military sphere was in the conduct of warfare. Weapons and technology remained largely static through the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, but 18th-century operational strategy underwent massive restructuring. Sieges became infrequent to the point of near-irrelevance, a new emphasis arose towards the destruction of enemy armies as well as their outmaneuvering, and invasions of enemy territory occurred over broader fronts, thus introducing a plethora of strategic opportunities that made wars costlier and, just as importantly, more decisive.[55] Defeat for a European power now meant much more than losing isolated enclaves. Near-Carthaginian treaties intertwined whole national efforts—social, political, economic, and militaristic—into gargantuan collisions that severely upset international conventions as understood at the time. Napoleon's initial success sowed the seeds for his downfall. Not used to such catastrophic defeats in the rigid power system of 18th-century Europe, many nations found existence under the French yoke difficult, sparking revolts, wars, and general instability that plagued the continent until 1815, when the forces of reaction finally triumphed at the Battle of Waterloo.[56]

French colonial empire

The history of French colonial imperialism can be divided in two major eras: the first from the early 17th century to the middle of the 18th century, and the second from the early 19th century to the middle of the 20th century. In the first phase of expansion, France concentrated its efforts mainly in North America, the Caribbean and India, setting up commercial ventures that were backed by military force. Following defeat in the Seven Years' War, France lost its possessions in North America and India, but it did manage to keep the wealthy Caribbean islands of Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Martinique.

The second stage began with the

From 1815

After the exile of Napoleon, the freshly restored

First World War

In World War I, the French, with

Second World War

A variety of factors—ranging from smaller industrial base to low population growth and obsolete military doctrines—crippled the French effort at the outset of World War II. The Germans won the Battle of France in 1940 despite the French often having better planes and tanks than their opponents whereas they were lacking modern weaponry for the infantry, the main problem although was the unexistant doctrine to synchronize the tanks alongside the plane, as tanks were not used as a primary force but rather as support for infantry, without planning an anti-air protection for them. their use as primary force were made in very rare occasion, when commanded by Charles de Gaulle for example, only a tank crew division commander by the time of 1940.

Prior to the Battle of France, there were sentiments among many Allied soldiers, French and British, of pointless repetition; they viewed the war with dread since they had already beaten the Germans once, and images of that first major conflict were still poignant in military circles.

After the defeat, Vichy France cooperated with the Axis powers until 1944. Charles de Gaulle exhorted the French people to join the allied armies, while the French Vichy forces participated in direct action against Allied forces, inflicting casualties in some cases.

The

Post-1945 warfare

Following the 1939–45 war, decolonization spread through the former European empires.

Following the

By 1960 France had lost its direct military influence over all of its former colonies in Africa and Indochina. Nonetheless, several colonies in the Pacific, Caribbean, Indian Oceans and South America remain French territory to this day and France kept a form of indirect political influence in Africa colloquially known as the Françafrique.

As

France intervened in various post-colonial conflicts, supporting former colonies (

As a nuclear power and having some of the best trained and best equipped forces in the world, the French military has now met some of its primary objectives which are the defense of national territory, the protection of French interests abroad, and the maintenance of global stability. Conflicts indicative of these objectives are the

African interventions during the early 21st century include

Hollande also proposed French military involvement in the

France has encouraged military cooperation at an EU level, starting with the formation of the

Topical subjects

French Air and Space Force

The

A perennial problem for the French Navy was the strategic priorities of France, which were first and foremost tied to its European ambitions. This reality meant that the army was often treated better than the navy, and as a result, the latter suffered in training and operational performance.

Later in the 19th century, the navy recovered and became the second finest in the world after the Royal Navy. It conducted a successful blockade of Mexico in the

Currently, French naval doctrine calls for two aircraft carriers, but the French currently only have one, the Charles de Gaulle, due to restructuring. The navy is in the midst of some technological and procurement changes; newer submarines are under construction and Rafale aircraft (the naval version) are currently replacing older aircraft.

Foreign Legion

The

Following participation in Africa and in the Carlist Wars in Spain, the Legion fought in the Crimean War and the Franco-Austrian War, where they performed heroically at the Battle of Magenta, before earning even more glory during the French intervention in Mexico. On April 30, 1863, a company of 65 legionnaires was ambushed by 2,000 Mexican troops at the Hacienda Camarón; in the resulting Battle of Camarón, the legionnaires resisted bravely for several hours and inflicted 300–500 casualties on the Mexicans while 62 of them died and three were captured.[80] One of the Mexican commanders, impressed by the memorable intransigence he had just witnessed, characterized the Legion in a way they've been known ever since, "These are not men, but devils!"[81]

In World War I, the Legion demonstrated that it was a highly capable unit in modern warfare. It suffered 11,000 casualties in the Western Front while conducting brilliant defenses and spirited counter-attacks.[82] Following the debacle in the Battle of France in 1940, the Legion was split between those who supported the Vichy government and those who joined the Free French under de Gaulle. At the Battle of Bir Hakeim in 1942, the Free French 13th Legion Demi-Brigade doggedly defended its positions against a combined Italian-German offensive and seriously delayed Rommel's attacks towards Tobruk. The Legion eventually returned to Europe and fought until the end of the Second World War in 1945. It later fought in the First Indochina War against the Viet Minh. At the climactic Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, French forces, many of them legionnaires, were completely surrounded by a large Vietnamese army and were defeated after two months of tenacious fighting. French withdrawal from Algeria led to the collapse of the French colonial empire. The legionnaires were mostly used in colonial interventions, so the destruction of the empire prompted questions about their status. Ultimately, the Legion was allowed to exist and participated as a rapid reaction force in many places throughout Africa and around the world.[83]

See also

- History of French foreign relations

- Military of France

- Military history of France during World War II

- Norman Conquest of England

- Marshals of France

- List of notable French military leaders

- List of French wars and battles

- Deployments of the French military

- List of battles involving France (disambiguation)

- Social background of officers and other ranks in the French Army, 1750–1815

- French and Indian Wars

Notes

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 101. "Washington's success in keeping the army together deprived the British of victory, but French intervention won the war."

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2001). "The Cash Nexus: Money and Power in the Modern World, 1700-2000; p.25-27". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- ^ William Roosen, The age of Louis XIV: the rise of modern diplomacy. p. 55

- ^ Brooks pp. 46–7, 84–5, 108–9.

- ^ William Thompson, Great power rivalries. p. 104

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 234

- ^ Kay, Sean. NATO and the future of European security. p. 43

- ^ Jolyon Howorth and Patricia Chilton, Defence and dissent in contemporary France. p. 153

- ^ Inc, Time (13 July 1953). "LIFE". Time Inc. Retrieved 6 May 2018 – via Google Books.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Alfred Bradford and Pamela Bradford, With arrow, sword, and spear: a history of warfare in the ancient world. p. 213

- De Bello Gallico, Caesar claims a Gallic relief force of 250,000 men, but the logistical requirements for such a huge army were beyond anything the Gauls could procure. It is likely that Caesar inflated the figures to make his victory seem more impressive.

- ^ Jim Bradbury, The Routledge companion to medieval warfare. p. 109

- ^ Jim Bradbury, The Routledge companion to medieval warfare. p. 110

- ^ J. M. Roberts, History of the World. p. 384

- ^ Brooks, Richard (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 46

- ^ Brooks p. 47

- ^ French Medieval Armies and Navies, Xenophon Group. Accessed March 20, 2006

- ^ French Medieval Armies and Navies, Xenophon Group. Accessed March 20, 2006

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 53

- ^ Brooks p. 50

- ^ Brooks p. 50

- ^ Andrew Jotischky, Crusading and the Crusader States. p. 37. The theory that argues for sociological and economic rather than spiritual motivation provides regional examples where noble fathers would give their lands to the oldest surviving son, meaning younger sons would be left landless and looking for somewhere to go (the Crusades, in this case). Problems with the theory include, but are not limited to, the fact that there is no proof that younger sons formed the majority of the crusaders, the response to the crusading movement was just as strong in areas with equitable inheritance systems, and, since they were in many ways bound to the wishes and the decisions of their nobles, knights often had little individual choice in whether they would participate in a crusade.

- ^ Jotischky p. 37

- ^ "Discover Islamic Art Virtual Exhibitions - Al-Franj: the Crusaders in the Levant - Introduction". www.discoverislamicart.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "- Hosanna Lutheran Church". www.welcometohosanna.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ David Eltis, The military revolution in sixteenth-century Europe. p. 12

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 59. "Much has been made of the success of the English longbow. However, it was not a war-winning weapon. Reliance on this defensive weapon on the battlefield gave the initiative to the French.."

- ^ Brooks p. 59. (continuing from last comment) "...its victories also depended on the French bungling their attack. The English were fortunate that their opponent failed to get it right three times in a 70-year period."

- ^ Trevor Dupuy, Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. p. 450

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 59. "The major defeats of the French by the English boosted French military thought. A recently discovered document of the French battle plan for the Agincourt campaign shows how carefully the French thought about ways of defeating the English. In the event, the plan could not be fully executed because the battlefield at Agincourt was too narrow for the French forces to fully deploy."

- ^ French Medieval Armies and Navies, Xenophon Group. Accessed March 20, 2006

- ^ Jeremy Black, Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492-1792. p. 49

- ISBN 9781326256524.

- ^ John A. Lynn, The Wars of Louis XIV. p. 8

- ^ James Wood, The King's Army. p. 131

- ^ Wood p. 132

- ^ Kemal Karpat, The Ottoman state and its place in world history. p. 52

- ^ Jamel Ostwald, Vauban under siege. p. 7

- ^ Lynn p. 16 (preface)

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 84

- ^ Jackson Spielvogel, Western Civilization: Since 1500. p. 551

- ^ Lester Kurtz and Jennifer Turpin, Encyclopedia of violence, peace and conflict, Volume 2. p. 425

- ^ David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 136

- ^ John R. Elting, Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée. p. 35. The opening words are mundane, but they helped pave the way for a new era in human history, one where militarism became entrenched in national culture: "From this moment until our enemies shall have been driven from the territory of the Republic, all Frenchmen are permanently requisitioned for the service of the armies."

- ^ T. C. W. Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars. p. 109

- ^ John R. Elting, Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée. p. 28–29. Aristocratic officers deserted gradually, not suddenly. Furthermore, desertion rates depended upon the service: cavalry officers were more likely to leave the army than their artillery counterparts.

- ^ Parker, Geoffrey. The Cambridge history of warfare. p. 189

- ^ Peter Paret, Clausewitz and the State. p. 332

- ^ John A. Lynn, The Wars of Louis XIV. p. 28

- ^ Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. p. 43. Lyons writes, France had a large population by European standards, numbering over 29 million in 1800. This was more than the population of the Habsburg Empire (20 million), more than double the population of England (about 12 million), and more than four times the population of Prussia (6 million).

- ^ Lester Kurtz and Jennifer Turpin, Encyclopedia of violence, peace and conflict, Volume 2. p. 425

- ^ David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon. p. 758

- ^ Chandler p. 162

- ^ Todd Fisher & Gregory Fremont-Barnes, The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. p. 186. "Up to 1792,...conflicts were, of course, those of kings, and followed the pattern of eighteenth-century warfare: sovereigns sought limited objectives and entertained no desire to overthrow their adversaries' ruling (and indeed usually ancient) dynasty. The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 altered this pattern forever and international relations underwent some radical changes as a result."

- ^ Conrad Phillip Kottak, Cultural Anthropology. p. 331

- ^ Richard Brooks (editor), Atlas of World Military History. p. 129

- Alsace-Lorraine, revanchismin French politics made certain that the army was carefully nurtured and well-treated because it was viewed as the only instrument through which France could overcome the humiliations of 1870.

- ^ de la Gorce p. 48

- ^ Hew Strachan, The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. p. 280

- ^ John Keegan, The Second World War. p. 64

- ^ Keegan p. 61

- ^ Boyce, French Foreign and Defence Policy. p. 185

- ^ Boyce p. 185

- ^ F. Roy Willis, France, Germany, and the New Europe, 1945-1967. p. 9

- ^ Cody, Edward (12 March 2009). "After 43 Years, France to Rejoin NATO as Full Member". Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Charles Hauss, Politics in France. p. 194

- ^ "France emerges as key U.S. ally against Syria". USA Today. 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (31 October 2013). "France Dissolves Symbolic Regiment Based In Germany". Defense News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013.

- ^ Royal Air Force Museum Archived 2009-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shlomo Aloni, Israeli Mirage and Nesher Aces. p. 6

- ^ French airforce adds home-grown fighter plane to its arsenal Agence-France Presse. Accessed November 7, 2006

- ^ Jean-Claude Castex, Dictionnaire des batailles navales franco-anglaises, Presses de l'Université Laval, 2004, p. 21

- ^ Jean-Claude Castex, Dictionnaire des batailles navales franco-anglaises, Presses de l'Université Laval, 2004, p.21

- ^ Russell Weigley, The age of battles: the quest for decisive warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. pp. 158–9

- ^ Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August. p. 166

- ^ David Jordan, The History of the French Foreign Legion. p. 10

- ^ Jordan p. 14

- ^ Byron Farwell, The encyclopedia of nineteenth-century land warfare. p. 155

- ^ David Jordan, The History of the French Foreign Legion. p. 34

- ^ Jordan p. 67

- ^ Jordan p. 94

Works cited

- Aloni, Shlomo. Israeli Mirage and Nesher Aces. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-653-4

- ISBN 0-521-47033-1

- Blanning, T.C.W. The French Revolutionary Wars. London: Hodder Headline Group, 1996. ISBN 0-340-56911-5

- Boyce, Robert. French Foreign and Defence Policy, 1918–1940. Oxford: CRC Press, 1998. ISBN 0-203-97922-2

- Bradbury, Jim. The Routledge companion to medieval warfare. New York: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-22126-9

- Bradford, Alfred and Pamela. With arrow, sword, and spear: a history of warfare in the ancient world. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. ISBN 0-275-95259-2

- Brooks, Richard (editor). Atlas of World Military History. London: HarperCollins, 2000. ISBN 0-7607-2025-8

- ISBN 0-02-523660-1

- Chilton, Patricia and Howorth, Jolyon Howorth. Defence and dissent in contemporary France Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 1984. ISBN 0-7099-1280-3

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. New York: HarperCollins, 1993. ISBN 0-06-270056-1

- Elting, John R. Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée. New York: Da Capo Press Inc., 1988. ISBN 0-306-80757-2

- Eltis, David. The military revolution in sixteenth-century Europe. New York: I. B. Tauris, 1998. ISBN 1-86064-352-3

- Farwell, Byron. The encyclopedia of nineteenth-century land warfare. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 0-393-04770-9

- Fisher, Todd & Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1-84176-831-6

- de la Gorce, Paul Marie. The French Army: A Military-Political History. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1963.

- Hauss, Charles. Politics in France. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007. ISBN 1-56802-670-6

- Jordan, David. The History of the French Foreign Legion. Spellmount Limited, 2005. ISBN 1-86227-295-6

- Jotischky, Andrew. Crusading and the Crusader States. Pearson Education Limited, 2004. ISBN 0-582-41851-8

- Karpat, Kemal. The Ottoman state and its place in world history. Leiden: Brill, 1974. ISBN 90-04-03945-7

- Kay, Sean. NATO and the future of European security. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998. ISBN 0-8476-9001-6

- ISBN 0-670-82359-7

- Kottak, Conrad. Cultural Anthropology. Columbus: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2005. ISBN 0-07-295250-4

- Kurtz, Lester and Turpin, Jennifer. Encyclopedia of violence, peace and conflict, Volume 2. New York: Academic Press, 1999. ISBN 0-12-227010-X

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1994. ISBN 0-312-12123-7

- Lynn, John A. Giant of the Grand Siècle: The French Army, 1610–1715. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-521-57273-8

- Lynn, John A. The Wars of Louis XIV. London: Longman, 1999. ISBN 0-582-05629-2

- Ostwald, Jamel. Vauban under siege. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ISBN 90-04-15489-2

- Paret, Peter. Clausewitz and the State. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-691-13130-9

- Parker, Geoffrey. The Cambridge history of warfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-85359-1

- ISBN 0-19-521043-3

- Roosen, William. The age of Louis XIV: the rise of modern diplomacy. Edison: Transaction Publishers, 1976. ISBN 0-87073-581-0

- Spielvogel, Jackson. Western Civilization: Since 1500. Florence: Cengage Learning, 2008. ISBN 0-495-50287-1

- ISBN 0-19-289325-4

- Thompson, William. Great power rivalries. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1999. ISBN 1-57003-279-3

- ISBN 0-345-38623-X

- Weigley, Russell. The age of battles: the quest for decisive warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-253-21707-5

- Willis, F. Roy. France, Germany, and the New Europe, 1945–1967. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1968. ISBN 0-8047-0241-1

- Wood, James. The King's Army. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-52513-6

Further reading

- Blaufarb, Rafe. The French army 1750–1820: Careers, talent, merit (Manchester University Press, 2021).

- Clayton, Anthony. Paths of glory: the French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell, 2003.

- ISBN 0-399-15238-5

- Doughty, Robert A. Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War (2008), 592pp; excerpt and text search

- Forrest, Alan. Conscripts and Deserters: The Army and French Society During the Revolution and Empire (1989)

- Forrest, Alan. Napoleon's Men: The Soldiers of the Revolution and Empire (2002)

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth. The French Army and the First World War (2014), 486 pages; comprehensive scholarly history.

- Holroyd, Richard. "The Bourbon Army, 1815–1830." Historical Journal 14, no. 3 (1971): 529–52. online.

- Kinard, Jeff. Artillery: an illustrated history of its impact. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2007. ISBN 1-85109-556-X

- Nolan, Cathal. Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization (2008)

- Nolan, Cathal. The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650 (2 vol. 2006)

- Pichichero, Christy. The Military Enlightenment: War and Culture in the French Empire from Louis XIV to Napoleon (2018) online review

- Porch, Douglas. "The French Army Law of 1832." Historical Journal 14, no. 4 (1971): 751–69. online.

- Porch, Douglas. The March to the Marne: The French Army 1871–1914 Cambridge University Press (2003) ISBN 978-0521545921

- Scott, Samuel F. From Yorktown to Valmy: the transformation of the French Army in an age of revolution (University Press of Colorado, 1998)

- Thoral, Marie-Cécile. From Valmy to Waterloo: France at War, 1792–1815 (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011)

Historiography and memory

- Forrest, Alan. The Legacy of the French Revolutionary Wars: The Nation-in-Arms in French Republican Memory (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

- Messenger, Charles, ed. Reader's Guide to Military History (2001) 948pp; Evaluation of thousands of books on military history, many of them involving France.

In French

- Bertaud, Jean-Paul, and William Serman. Nouvelle histoire militaire de la France, 1789–1919 (Paris, Fayard: 1998); 855pp

External links

- French Military Terms Adopted by the English Language

- French military participation from 1800 to 1999

- The French Army: Royal, Revolutionary and Imperial

- An excellent guide to French Medieval warfare

- France in the American Revolution

- French Army from Revolution to the First Empire, Illustrations by Hippolyte Bellangé from the book P.-M. Laurent de L`Ardeche «Histoire de Napoleon», 1843

- The French Military in Africa (2008) – Council on Foreign Relations