Military history of Thailand

The military history of

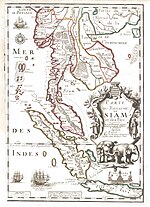

Sukhothai Period (1238–1350)

The Siamese military state emerged from the disintegration in the 14th century of the once powerful Khmer Empire. Once a powerful military state centred on what is today termed Cambodia, the Khmer dominated the region through the use of irregular military led by captains owing personal loyalty to the Khmer warrior kings, and leading conscripted peasants levied during the dry seasons. Primarily based around its infantry, the Khmer army was typically reinforced by war elephants and later adopted ballista artillery from China.

By the end of the period, indigenous revolts amongst Khmer territories in

Ayutthaya Period (1350–1767)

After 1352 Ayutthaya became the main rival to the failing Khmer empire, leading to Ayutthayan

Ayutthaya–Lan Na War (1441–1474)

In 1441, a war started between the Kingdom of Ayutthaya and the Kingdom of Lan Na. Neither side were able to overcome the other and they were left in a stalemate.

Burmese–Siamese War (1547–1549)

In 1547, King Tabinshwehti invaded Siam and almost captured Ayutthaya, but had to retreat. It was a Siamese pyrrhic victory as they lost the Tenasserim Coast to Burma in exchange for peace.

Burmese–Siamese War (1563–1564)

In 1563, King Bayinnaung invaded Siam and managed to conquer it as vassals. The Siamese tried to revolt against Burmese rule

The use of war elephants continued, with some battles seeing personal combat between commanders on elephants.

Burma successfully invaded Ayutthaya again in 1767, this time burning the capital and temporarily dividing the country. General, later King,

Military competition for regional hegemony continued, with continued Siamese military operations to maintain their control over the kingdom of Cambodia, and Siamese support for the removal of the hostile

Siam and the European military threat (1826–1932)

The

Under

Siam's response under King

The closing act of this struggle was the French occupation of eastern Thai territory in the

In 1893 the French ordered their navy to sail up the Chao Phraya River to Bangkok. With their guns trained on the Siamese royal palace, the French delivered an ultimatum to the Siamese to hand over the disputed territories and to pay indemnities for the fighting so far. When Siam did not immediately comply unconditionally to the ultimatum, the French blockaded the Siamese coast. Unable to respond by sea or on land, the Siamese submitted fully to the French terms, finding no support from the British.[12] The conflict led to the signature of the Franco-Siamese Treaty in which the Siamese conceded Laos to France, an act that led to a significant expansion of French Indochina.

In 1904 the French and the British put aside their differences with the

Second World War and Alliance with Japan (1932–1945)

For Thailand – renamed from

The conflict fell into three broad phases. During the initial phase following the

During the second phase, Japan took advantage of the weakening British hold on the region to invade Siam, seeing the country as an obstacle on the route south to British-held

By the final stages of the war, however, the weakening position of Japan across the region and the Japanese requisition of supplies and materiel reduced the military benefits to Siam, turning an unequal alliance into an increasingly obvious occupation. Allied air power achieved superiority over the country,

The conflict highlighted the new importance of air power across the region, for example the use of dive bombers against French troops in 1941[16] or the use of air reconnaissance in the northern mountains.[21] It had also highlighted the importance of well-trained pilots to effective air war.[22] Ultimately, the conflict emphasised the challenges of logistics across often impassable terrain, which generated expensive military campaigns – a feature to reemerge in the postwar period during the conflicts in French Indochina.

Thailand and regional Communism (1945–90)

Thailand's military history in the post-war period was dominated by the growth of

Whilst the

The

Post-communist period

The last twenty years of Thailand's military history has been dominated less by the threat of external attack, but by the role of the Thai military in internal politics. For most of the 1980s, Thailand was ruled by prime minister Prem Tinsulanonda, a democratically inclined leader who restored parliamentary politics. Thereafter the country remained a democracy apart from a brief period of military rule from 1991 to 1992, until, in 2006 mass protests against the Thai Rak Thai party's alleged corruption prompted the military to stage a coup d'état. A general election in December 2007 restored a civilian government, but the issue of the Thai military's frequent involvement in domestic politics remains.

Meanwhile, the long-running

The Thai military maintains strong regional relations under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) organisation, illustrated by the annual Cobra Gold exercises, the latest in 2018, involving soldiers from Thailand, the US, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. The exercises are the largest military exercises in Southeast Asia.[34][35] This association, bringing together many former enemies, plays an important part in ensuring ongoing peace and stability across the region.

References

- ^ For example the fight between Burmese crown prince Mingyi Swa and by Siamese King Naresuan in the battle of Battle of Yuthahatthi on what is now reckoned as 18 January 1593, and observed as Armed Forces Day.

- ^ Arjarn Tony Moore/Khun Clint Heyliger Siamese & Thai Hero's & Heroines Archived 12 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Royal Thai Army Radio and Television King Taksin's Liberating Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9971-69-328-3.

- ISBN 0-521-35505-2.

- ^ Buttinger, Joseph (1958). The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. Praeger, p. 305.

- ^ Search-thais.com Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De la Bissachere, cited Nossov, K. War Elephants, 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Heath, I. Armies of the Nineteenth Century: Asia, Burma and Indo-China, 2003, p. 182.

- ^ a b Stuart-Fox 1997[dead link]

- ^ ISBN 9780700715312. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b Ooi 2004[dead link]

- ^ U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Office of the Geographer, "International Boundary Study: Malaysia - Thailand Boundary" No. 57 Archived 16 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, 15 November 1965.

- ^ "90th Anniversary of World War I. This Is The History of Siamese Volunteer Corps". Thai Military Information Blog. 10 November 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Thailand and the First World War". First World War. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b Young, Edward M. (1995) Aerial Nationalism: A History of Aviation in Thailand. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Hesse d'Alzon, Claude. (1985) La Présence militaire française en Indochine. Château de Vincennes: Publications du service historique de l'Armée de Terre.

- ^ a b E. Bruce Reynolds. (1994) Thailand and Japan's Southern Advance 1940–1945. St. Martin's Press.

- ^ "Thailand and the Second World War 1941- 45". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Judith A. Stowe. (1991) Siam becomes Thailand: A Story of Intrigue. Hurst & Company.

- ^ "The Drive on Kengtung". Archived from the original on 31 March 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Elphick, Peter. (1995) Singapore, the Pregnable Fortress: A Study in Deception, Discord and Desertion. Coronet Books.

- ^ The United States Army Homepage Archived 16 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Milestones: 1953–1960 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Ruth, Richard A (7 November 2017). "Why Thailand Takes Pride in the Vietnam War". New York Times. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Stanton, 'Vietnam Order of Battle,' 270–271.

- ^ "6ตุลา".

- ^ "Thailand Communist Insurgency 1959-Present". Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ The New York Times

- ^ "Global Security". Retrieved 3 December 2014.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "Unk". Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Crispin, Shawn W. "What Obama means to Bangkok". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Head, Jonathan. "Thailand's savage southern conflict". BBC. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Parameswaran, Prashanth (31 January 2018). "What Will the 2018 Cobra Gold Military Exercises in Thailand Look Like?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "Cobra Gold 2009 Gallery". Thai Military Information Blog. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

Further reading

- Ruth, Richard A (September 2010). In Buddha's Company; Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War (Paper ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824834890. Retrieved 24 August 2018.