Prayer rug

A prayer rug or prayer mat is a piece of fabric, sometimes a

during prayer.In Islam, a prayer mat is placed between the ground and the worshipper for cleanliness during the various positions of

Prayer rugs are also used by some

Many new prayer mats are manufactured by weavers in a factory. The design of a prayer mat is based on the village it came from and its weaver. These rugs are usually decorated with many beautiful geometric patterns and shapes. They are sometimes even decorated with images. These images are usually important Islamic landmarks, such as the Kaaba, but they are never animate objects.[5] This is because the drawing of animate objects on Islamic prayer mats is forbidden.

For Muslims, when praying, a niche, representing the mihrab of a mosque, at the top of the mat must be pointed to the Islamic center for prayer, Mecca. All Muslims are required to know the qibla or direction towards Mecca from their home or where they are while traveling. Oriental Orthodox Christians position their prayer rugs so that they face east, the direction of prayer towards which they offer prayer.

History and use

In the Baha'i Faith

In the

In Christianity

Prayer rugs are used in some traditions of

During the

The Armenian Apostolic Church, an Oriental Orthodox Christian denomination, has a long tradition of prayer rugs with Christian symbols woven in them; these have been found in places as far as Shirvan.[12][13][14] One of the oldest is the Saint Hrip'sime Rug, which was woven in 1202 A.D. and originates in the village of Banants, located in what is now Gandja.[14][15]

In Islam

In

A prayer rug is characterized by a niche at one end, representing the

In Islam, the prayer rug has a very strong symbolic meaning and traditionally taken care of in a holy manner. It is disrespectful for one to place a prayer mat in a dirty location (as Muslims have to be clean to show their respect to God) or throw it around in a disrespectful manner.[18]

Prayer rugs are usually made in the towns or villages of the communities who use them and are often named after the origins of those who deal and collect them. The exact pattern will vary greatly by original weavers and the different materials used. Some may have patterns, dyes and materials that are traditional/native to the region in which they were made. Prayer rugs' patterns generally have a niche at the top, which is turned to face Mecca. During prayer the supplicant kneels at the base of the rug and places their hands at either side of the niche at the top of the rug, their forehead touching the niche. Typical prayer rug sizes are approximately 2.5 ft × 4 ft (0.76 m × 1.22 m) to 4 ft × 6 ft (1.2 m × 1.8 m), enough to kneel above the fringe on one end and bend down and place the head on the other.

Some countries produce textiles with prayer rug patterns for export. Many modern prayer rugs are strictly commercial pieces made in large numbers to sell on an international market or tourist trade.

-

Fragment of a flat-weave (zilu) saf carpet. Dated to the first half of the 14th century, it is the earliest extant example of a flat-weaven carpet from Islamic Iran. Hermitage Museum

-

Mamluk prayer rug. c. 1500. Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin

-

"Re-entrant" or "keyhole" prayer mat, also called a Bellini carpet, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century. The mat symbolically describes the environment of a mosque, with the entrance (the "keyhole"), and the mihrab (the forward corner) with its hanging mosque lamps. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

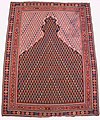

Niche prayer carpet. Turkey, 2nd half of the 16th century. Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

-

A row niche kilim of a saf kind, laid out in mosques to give room to several worshipers next to each other. Turkey, 18th century. Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin

-

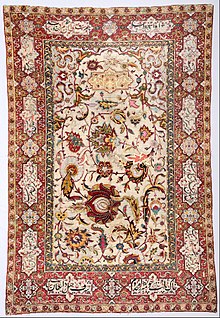

"Senneh" prayer rug. Sanandaj, late 18th–early 19th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Islamic rugs in Lutheran Churches

The Saxon

Transylvania, like the other Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, never came under direct Turkish occupation. Until 1699 it had the status of an autonomous Principality, maintaining the Christian religion and own administration but paying tribute to the Ottoman Porte. By contrast, following the

Rugs came into the ownership of the Reformed Churches, mainly as pious donations from parishioners, benefactors or guilds. In the 16th century, with the coming of the Reformation, the number of figurative images inside the churches was drastically reduced. Frescoes were white-washed or destroyed, and the many sumptuous winged altar-pieces were removed maintaining exclusively the main altar piece. The recently converted parishioners thus perceived the church as a large, cold and empty space, which required at least some decoration. Traces of the mural decoration were found during modern restorations in some Protestant Churches as for instance at Malâncrav.[citation needed]

In this situation the Oriental rugs, created in a world that was spiritually different from Christianity, found their place in the Reformed churches which were to become their main custodians. The removal from the commercial circuit and the fact that they were used to decorate the walls, the pews and the balconies but not on the floor was crucial for their conservation over the years.

After the Siege of Vienna of 1682 the Ottomans suffered several defeats by hand of the Habsburg army. In 1687 the rulers of Transylvania recognized the suzerainty of the Habsburg emperor Leopold I. Generally the end of the Turkish rule in Transylvania is associated with the Peace Treaty of 1699, but in fact this happened more than a decade earlier. The last decades of the 17th century marked a decline of the rug trade between Transylvania and Turkey which affected the carpet production in Anatolia. Shortly after the turn of the century the commercial rugs based on Lotto, Bird or Transylvanian patterns ceased to be woven.[19][pages needed]

Interactive prayer mats

Interactive prayer mats, also known as smart prayer mats or digital prayer rugs, are a recent development in the field of prayer rugs. These mats are designed to enhance the spiritual experience of Muslims during prayer by incorporating technology into the traditional practice of prayer, and for educational purposes.[20]

Name variations

| Region/country | Language | Main |

|---|---|---|

Arab World |

Arabic |

سجادة الصلاة سجاجيد الصلاة (Sajjādat aṣ-ṣalāt), pl. سجاجيد الصلاة (Sajājīd aṣ-ṣalāt) |

| Greater Iran | Persian |

جانماز (Jānamāz) |

Hindi, Urdu |

जानमाज़ / جا نماز (Jaa-namaaz)

सजदागाह / سجدہ گاہ (Sajda-gaah) | |

| Pashtunistan | Pashto | د لمانځه پوزی |

| Bangladesh, West Bengal | Bengali | জায়নামাজ/জায়নামায (Jāynamāz) |

Bosnia |

Bosnian | sedžada, serdžada, postećija |

| Indonesia | Basa Sunda |

Sajadah |

| Malaysia | Malay |

Sejadah |

Gambia, Mauritania |

Wolof | Sajadah |

| Nigeria, Niger, Ghana, Cameroon | Hausa | Buzu na salla, dadduma, darduma |

| South Kalimantan | Banjar |

Pasahapan |

| Iraqi Kurdistan | Sorani | بەرماڵ |

| Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan | Kazakh, Kyrgyz | Жайнамаз (Jainamaz) |

| Uzbekistan | Uzbek | Joynamoz |

| Greater Somalia | Somali | sijayad, salli, Sajadat |

| Turkey, Azerbaijan | Azeri |

Seccade, canamaz |

| Turkmenistan | Turkmen | Namazlyk |

| Kerala | Malayalam |

നിസ്കാരപ്പടം, Niskarappadam |

See also

- Eagle rug

- Islamic art

- Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

- Persian embroidery

- Podruchnik, a cushion for worshipper's hands among Russian Old Believer Christians

- Tradition of removing shoes in the home and houses of worship

- Turbah, a piece of clay commonly used in Shia Islam as a place of prostration

Notes

References

- ^ "Carpet". Discover Islamic Art.

- ^ a b c d Kosloski, Philip (16 October 2017). "Did you know Muslims pray in a similar way to some Christians?". Aleteia. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d Bishop Brian J Kennedy, OSB. "Importance of the Prayer Rug". St. Finian Orthodox Abbey. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ a b Basenkov, Vladimir (10 June 2017). "Vladimir Basenkov. Getting To Know the Old Believers: How We Pray". Orthodox Christianity. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8228-0545-9.

This Moslem prayer rug, too, shows the Kaaba in order to distinguish itself clearly from Christian carpets, whose Armenian border it kept.

- ^ Shehimo: Book of Common Prayer. Diocese of South-West America of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. 2016. pp. 5, 7, 12.

- ^ "Prostration/ Kneeling (Kumbideel)". Malankara World. 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Duffner, Jordan Denari (13 February 2014). "Wait, I thought that was a Muslim thing?!". Commonweal. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Neff, David (19 May 1997). "Going to the Prayer Mat for Jesus". Christianity Today. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch (2009). A History of Christianity. Penguin Group. p. 258.

- ^ "Shwebo and his Monastery". Columban Interreligious Dialogue. 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-9672120-1-2.

Surprisingly, Arab sources acknowledge the supremacy of Christian Armenian prayer rugs, even though these rugs are often thought of as the quintessential Islamic art form.

- ^ Raphaelian, Harry M. (1953). The Hidden Language of Symbols in Oriental Rugs. A. Sivas. p. 58.

Caucasian prayer rugs of Shirvan and Kabistan, usually Armenian products, show evidence of Christian symbolism in woven niches that have no affinity with mosque architecture.

- ^ a b Keshishian, James Mark; Manuelian, Lucy Der (1994). Inscribed Armenian Rugs of Yesteryear. Near Eastern Art Research Center. p. 41.

Authors fail to mention Armenian prayer rugs which were probably an established tradition in Armenia before the emergence of Islam in the seventh century. The oldest known prayer rug is the famous Hrip'sime Rug, published by Alois Riegel in 1895. The inscription on this important rug states that it was woven in 1202 and indicates that it was associated with individuals in the Armenian village of Banants in the Gandzak region, the historic Armenian district of Artsakh-Gharabagh, which is present-day Kirovabad.

- ISBN 978-0-912804-18-7.

- ^ Komaroff & Carboni, p. 262.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen, Richard; Dimand, Maurice S.; Mackie, Louise W.; Ellis, Charles Grant (1974). Prayer Rugs. Washington, DC: Textile Museum. pp. 11, 19.

- ^ "The History Of Prayer Rugs". Oriental Rug Salon. 2022-03-30. Retrieved 2024-06-01.

- ISBN 88-7620-752-X.

- ISBN 978-3-03921-181-4.

Bibliography

- Linda Komaroff; Stefano Carboni (2002). The Legacy of Genghis Khan. Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09691-7.

Further reading

- "prayer rug." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 23 Oct. 2008 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/474169/prayer-rug.

- Faid, Abbo Muhammed Samir. "Islam" All Experts. 16 Mar 2005. <https://web.archive.org/web/20100224195249/http://www.liu.edu/CWIS/CWP/library/workshop/citmla.htm>

External links

Media related to Prayer rugs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prayer rugs at Wikimedia Commons- Importance of the Prayer Rug by Bishop Brian J Kennedy, OSB - Holy Trinity Celtic Orthodox Church