Viral meningitis

| Viral meningitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Aseptic meningitis |

| |

| Viral meningitis causes inflammation of the meninges. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Viral meningitis, also known as aseptic meningitis, is a type of

Viruses are the most common cause of

In most cases, there is no specific treatment, with efforts generally aimed at relieving symptoms (headache, fever or nausea).[6] A few viral causes, such as HSV, have specific treatments.

In the United States, viral meningitis is the cause of more than half of all cases of meningitis.[7] With the prevalence of bacterial meningitis in decline, the viral disease is garnering more and more attention.[8] The estimated incidence has a considerable range, from 0.26 to 17 cases per 100,000 people. For enteroviral meningitis, the most common cause of viral meningitis, there are up to 75,000 cases annually in the United States alone.[8] While the disease can occur in both children and adults, it is more common in children.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Viral meningitis characteristically presents with

Babies with viral meningitis may only appear irritable, sleepy or have trouble eating.

Symptoms can vary depending on the virus responsible for infection. Enteroviral meningitis (the most common cause) typically presents with the classic headache, photophobia, fever, nausea, vomiting, and nuchal rigidity.[15] With coxsackie and echo virus' specifically, a maculopapular rash may be present, or even the typical vesicles seen with Herpangina.[15] Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) can be differentiated from the common presenting meningeal symptoms by the appearance of a prodromal influenza-like sickness about 10 days before other symptoms begin.[15] Mumps meningitis can present similarly to isolated mumps, with possible parotid and testicular swelling.[15] Interestingly, research has shown that HSV-2 meningitis most often occurs in people with no history of genital herpes, and that a severe frontal headache is among the most common presenting symptoms.[16][15] Patients with varicella zoster meningitis may present with herpes zoster (Shingles) in conjunction with classic meningeal signs.[15] Meningitis can be an indication that an individual with HIV is undergoing seroconversion, the time when the human body is forming antibodies in response to the virus.[1]

Causes

The most common causes of viral meningitis in the United States are non-polio

- Enteroviruses

- Enterovirus 71

- Echovirus

- Poliovirus (PV1, PV2, PV3)

- Hand foot and mouth disease

- Herpesviridae (HHV)

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1 / HHV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2 / HHV-2); also cause cold sores or genital herpes

- herpes zoster)

- Epstein–Barr virus (EBV / HHV-4); also causes infectious mononucleosis/"mono"

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV / HHV-5)

- AIDS

- La Crosse virus

- Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus(LCMV)

- Measles

- Mumps

- St. Louis encephalitis virus

- West Nile virus

Mechanism

Viral Meningitis is mostly caused by an

The barrier that the

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of viral meningitis is made by clinical history, physical exam, and several diagnostic tests.[21] Kernig and Brudzinski signs may be elucidated with specific physical exam maneuvers, and can help diagnose meningitis at the bedside.[15] Most importantly however, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is collected via lumbar puncture (also known as spinal tap). This fluid, which normally surrounds the brain and spinal cord, is then analyzed for signs of infection.[22] CSF findings that suggest a viral cause of meningitis include an elevated white blood cell count (usually 10-100 cells/μL) with a lymphocytic predominance in combination with a normal glucose level.[23] Increasingly, cerebrospinal fluid PCR tests have become especially useful for diagnosing viral meningitis, with an estimated sensitivity of 95-100%.[24] Additionally, samples from the stool, urine, blood and throat can also help to identify viral meningitis.[22] CSF vs serum c-reactive protein and procalcitonin have not been shown to elucidate whether meningitis is bacterial or viral.[14]

In certain cases, a CT scan of the head should be done before a lumbar puncture such as in those with poor immune function or those with increased intracranial pressure.[1] If the patient has focal neurological deficits, papilledema, a Glasgow Coma Score less than 12, or a recent history of seizures, lumbar puncture should be reconsidered.[14]

Differential diagnosis for viral meningitis includes meningitis caused by bacteria, mycoplasma, fungus, and drugs such as NSAIDS, TMP-SMX, IVIG. Further considerations include brain tumors, lupus, vasculitis, and Kawasaki disease in the pediatric population.[14]

Treatment

Because there is no clinical differentiation between bacterial and viral meningitis, people with suspected disease should be sent to the hospital for further evaluation.

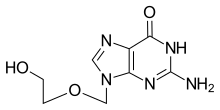

Herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus and cytomegalovirus have a specific antiviral therapy. For herpes the treatment of choice is aciclovir.[26] If encephalitis is suspected, empiric treatment with IV aciclovir is often warranted.[14]

Surgical management is indicated where there is extremely increased intracranial pressure, infection of an adjacent bony structure (e.g. mastoiditis), skull fracture, or abscess formation.[10]

The majority of people that have viral meningitis get better within 7–10 days.[27]

Epidemiology

From 1988 to 1999, about 36,000 cases occurred each year in the United States.[28] As recently as 2017, the incidence in the U.S. alone increased to 75,000 cases per year for enteroviral meningitis.[8] With the advent and implementation of vaccinations for organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza type B, and Neisseria meningitis, rates of bacterial meningitis have been in decline, making viral meningitis more common.[14] Countries without high rates of immunization still carry higher rates of bacterial disease.[14] While the disease can occur in both children and adults, it is more common in children.[1] Rates of infection tend to reach a peak in the summer and fall.[29] During an outbreak in Romania and in Spain viral meningitis was more common among adults.[30] While, people aged younger than 15 made up 33.8% of cases.[30] In contrast in Finland in 1966 and in Cyprus in 1996, Gaza 1997, China 1998 and Taiwan 1998, the incidence of viral meningitis was higher among children.[31][32][33][34]

Recent research

It has been proposed that viral meningitis might lead to inflammatory injury of the vertebral

The Meningitis Research Foundation is conducting a study to see if new

While there is some emerging evidence that bacterial meningitis may have a negative impact on cognitive function, there is no such evidence for viral meningitis.[38]

References

- ^ PMID 18174598.

- ^ "Epidemiology". Alaska Department of Health and Social Services.

- PMID 3990441.

- ^ "Meningitis, Viral" (PDF). lacounty.gov. Acute Communicable Disease Control Manual. County of Los Angeles Dept. of Public Health. March 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Meningitis | Viral | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- ^ "Viral Meningitis - Meningitis Research Foundation". www.meningitis.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

- S2CID 24087895.

- ^ S2CID 6003618.

- ^ a b c "Viral Meningitis - Brain, Spinal Cord, and Nerve Disorders - Merck Manuals Consumer Version". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Meningitis | McMaster Pathophysiology Review". www.pathophys.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- PMID 29368214.

- PMID 31747208. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ PMID 25015482.

- ^ )

- ^ S2CID 72334384.

- PMID 19559173.

- ^ Viral Meningitis at eMedicine

- ^ a b "Viral Meningitis: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2017-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - PMID 21413332.

- PMID 16474042.

- ^ "Diagnosis - Meningitis - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ a b "CSF analysis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ "CSF Analysis - Neurology - UMMS Confluence". wiki.umms.med.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- PMID 14524396. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ "Viral Meningitis Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmacologic Treatment and Medical Procedures, Patient Activity". 2017-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - PMID 15319091.

- ^ "Meningitis | Viral | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- S2CID 27311344.

- PMID 18174598.

- ^ PMID 21349608.

- PMID 3764348.

- ^ "1998—Enterovirus Outbreak in Taiwan, China—update no. 2". WHO. Archived from the original on May 29, 2004.

- ^ "1997—Viral meningitis in Gaza". WHO. Archived from the original on July 10, 2004.

- ^ "1996—Viral meningitis in Cyprus". WHO. Archived from the original on July 10, 2004.

- PMID 22909191.

- ^ "Using new genomic techniques to identify the causes of meningitis in UK children | Meningitis Research Foundation". www.meningitis.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- PMID 30641229.

- PMID 28837564.