Baghdadi Jews

Calcutta ) . Now mostly English and Hebrew | |

| Religion | |

|---|---|

| Judaism |

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad and elsewhere in the Middle East are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Beginning under the

These grew into a tight trading and kinship network across Asia with smaller Baghdadi communities being established beyond India in the mid-nineteenth century in

The

Precolonial origins

Though Jewish traders from the Middle East had crossed the Indian Ocean since ancient Rome, sources from the Mughal Empire first mention Jewish merchants from Baghdad trading with India in the 17th century.[10]

India was far from unknown to the Jewish merchants of the Middle East. Since ancient Rome the caravan route from India had ended in Aleppo and the spice trade had tied Basra, Yemen and Cairo to the Malabar Coast.[11] However, it was Persian-speaking Jewish merchants, close trading allies of the Jews of Baghdad, Basra and Aleppo Jews who first struck into the Indian heartland.[12]

As adventurers, mystics and merchants, they had been venturing to India since the Middle Ages on the back of invasions of the subcontinent launched by Persian speaking rulers from what is now Iran and Afghanistan. Both Persian and Mughal sources record Jewish traders following the 16th century Mughal invasion of India launched by Emperor Babur.[12]

They rose to be traders and courtiers of the Mughals. Jewish advisors at the Court of Akbar the Great in Agra played a significant role in Akbar's liberal religious policies.[13] In Delhi, the syncretic Jewish mystic Sarmad Khasani was tutor to the Crown Prince Dara Shikoh before both were executed by Aurangzeb.[14] There were sufficient Jews in Mughal lands for British travelers to report that synagogues had been established there, but of which no trace or Jewish record remains.[12] These handful of Jews never established a permanent community but left legends and pathways for future settlers from Arabic speaking lands.[15]

Records of Jewish tradesmen traveling from Baghdad can be found from the early 17th century. These trading outposts and emerging migrant communities also saw Jews become courtiers to

The first permanent Baghdadi merchant colony in

.But it was around the early 19th century, in response to the tyrannical rule of Dawud Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Baghdad, who persecuted, extorted and imprisoned the leading Jewish families of the city, that whole clans started crossing the Indian Ocean to seek safety and fortune in Asia.[21] Dawud Pasha's misrule was when Baghdadi immigration towards Bombay and Calcutta became strong with the leading Sassoon, Ezra and Judah families departing for India.[5] This episode of persecution was the beginning of the Baghdadi Jewish diaspora with records of whole clans departing the city for Bombay, Calcutta, Aleppo, Alexandria and Sydney.[5]

Jewish life in the ancient communities of the

Colonial Asia

As Jews, primarily from Baghdad, Basra and Aleppo came to India as traders in the wake of the Portuguese, Dutch and British what became known as the Baghdadi communities grew fast. By the middle of the 19th century trade between Baghdad and India was said to be entirely in Jewish hands.[27] Within a generation Baghdadi Jews had established manufacturing and commercial houses of fabulous wealth, most notably the Sassoon, Ezra, Elias, Belilios, Judah and Meyer families.[28]

With the rise of British power in

Spurred by the immigration of some the leading Jewish families of Baghdad fleeing the persecution of

The rise in prominence of

Around these booming concerns, the Baghdadi Jewish communities of

Sponsored by the

From

Following the ban on the opium trade in the early twentieth century Baghdadi Jewish merchants invested in cotton and jute products as staple exports.[31] The sudden spike in demand for jute sandbags, building blocks for the trenches on the Western Front (World War I), made great fortunes amongst the Jewish merchants of Calcutta.[37]

At their heights, the communities of

Before

Those communities established beyond

Whilst

On the route between India and Singapore, a tiny Baghdadi community was in Penang, with a synagogue and Jewish cemetery, was established in the 1870s, but for most of its history never exceeded 50 families.[42] Further south from Singapore, in Indonesia, then the Dutch East Indies, a tiny Baghdadi community of spice merchants was established in Surabaya in Java in the 1880s.[43]

The most far flung Baghdadi outposts, never numbering more than fifty families, were established in Japan at the furthest reaches of the opium route. Baghdadi Jews from Iraq, Syria and Egypt, initially drawn to man the concessions of David Sassoon established tiny footholds in Nagasaki, Yokohama and Kobe.[44] The only Baghdadi synagogue in Japan, uniting small prayer groups, was Ohel Shelomoh opened by Jews from Aleppo in 1912.[44] Initially established in Nagasaki and Yokohama, the Baghdadi traders relocated to Kobe, which became its focal point, after an earthquake in 1923.[45]

As imperial jurisdictions consolidated, the Baghdadi Jews found themselves in a liminal situation in colonial Asia. They were considered neither Indian nor Western, Asian nor European and partnered with both Western and Indian interests.[46] Legally they lived in limbo, their citizenship often unclear, having inherited what was an early modern political order.[citation needed]

Prior to the

Beyond

As a result, the Baghdadi Jews were determined to prove themselves a loyalist community to British authorities throughout the colonial period. Baghdadi Jewish merchants operated as confidential agents of the

Baghdadi culture

The Baghdadi Jews, whilst spread across continents, operated a network of kinship and trust throughout the trading posts of the

The life of the Baghdadi kinship network on the opium route is best seen in the case of

Within these Baghdadi communities, the majority were of

Quite unlike

These great Baghdadi Jewish fortunes are deceptive, however, when it comes to what life was like for the overwhelming majority of the community. Far from wealthy, they lived on the edge of poverty, as peddlers, stall holders, mill workers, rickshaw men and other such jobs. The middle class Jews speculated in opium and acted as brokers.[17] Great distance existed between the leading Baghdadi Jewish families, such as the Ezra family and the Sassoon family, who grew ever richer and more British-oriented during this period, and the rest of the community.[52] Politically, the Baghdadi Jewish resembled an oligarchy, with all power and authority to represent the community towards colonial authorities being vested in the leading families, as it had been traditionally in the Middle East.[48]

Initially the Baghdadi Jewish communities that developed in

In the 20th century

Such

Religiously the Baghdadi Jews did not train their own

Throughout this period, the leading Baghdadi Jewish families set themselves up as sponsors of Jewish religious life in the

Postcolonial decline

As the

The Japanese occupation of

At the heart of the Baghdadi world, in India, the end of the war ushered in the implosion of the old order. At this point, ethnic strife, political violence and fear of civil war were widespread in India on the eve of

First the leading families, then the rest of the community began to emigrate on mass. This began a continuous exodus from

Postwar the imperial system and open borders that had made the transnational Baghdadi world possible disappeared. In Shanghai, communist victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949 closed the trading links community depended upon. Those that has fled the Japanese occupation chose not to return. By 1950, the community had all but vanished. Meanwhile, In Hong Kong, despite the benign conditions of British rule, emigration saw Baghdadi Jewish numbers fall to less than 70 by the 1960s.

In

A final wave of emigration, pushing the much reduced communities in

Despite this precipitous decline and dispersal of the Baghdadi Jewish communities, a handful of individual Baghdadi Jews would play pivotal roles in Asia's newly independent states. The first

The Baghdadi community, however, never saw their exodus as a tragedy. Memoirs written by Baghdadi Jewish authors spoke fondly

In the early twenty first century the Baghdadi communities of

Today synagogues and associations upholding Baghdadi Jewish traditions exist in Britain, Israel, Australia and the United States. But in the historic Baghdadi communities in Asia only the synagogues originally founded by Baghdadi Jews in both Hong Kong and Singapore continue to operate regular services.[66][67]

Families of Baghdadi Jewish descent continue to play a major role in Jewish life particularly in Great Britain, to which the leading families were drawn after the Second World War. Established in London, the Sassoon family enjoyed the friendship of Edward VII, established a baronetcy and saw Philip Sasson became a minister.[8] Meanwhile, other Baghdadi families such as the Reubens have played major role in the British economy whilst others have gained notable prominence in arts and journalism, such as Gerry Judah and Tim Judah.[68]

Cuisine

Traditional Baghdadi Jewish cuisine is a hybrid cuisine, with many

Synagogues

Pre-World War Two Baghdadi Communities in Asia

| City | Synagogue | Year Opened |

|---|---|---|

| Mumbai | Knesset Eliyahoo | 1884 |

| Mumbai | Magen David | 1864 |

| Kolkata | Magen David | 1884 |

| Hong Kong | Ohel Leah | 1902 |

| Penang | Penang Synagogue[70] | 1926; Closed 1976 |

| Pune | Ohel David | 1867 |

| Shanghai | Ohel Rachel | 1921 |

| Singapore | Maghain Aboth | 1878 |

| Singapore | Chesed El | 1905 |

| Yangon (Rangoon) | Musmeah Yeshua | 1896 |

| Yangon (Rangoon) | Beth El | 1932; closed by the end of WWII |

Post-World War Two wider Baghdadi and Iraqi Jewish Diaspora.

| City | Synagogue | Year Opened |

|---|---|---|

| London | Ohel David Eastern Synagogue | 1959 |

| Los Angeles | Kahal Joseph Congregation | 1959 |

| New York | Congregation Bene Naharayim | 1983 |

| New York | Babylonian Jewish Center | 1997 |

| Sydney | Beth Yisrael Synagogue | 1962 |

Notable Baghdadi Jews

- Yosef Hayyim (Ben Ish Chai)

- Channel Four.

- Esther Victoria Abraham, Indian model and actress.

- Shalom Obadiah Cohen, community leader and founder of the Jewish community in Calcutta.

- Bombay Municipal Corporation.

- Brian Elias, composer.

- Eli Amir, writer

- Edward Isaac Ezra, opium trader and real estate developer.

- Brian George, Israeli-born character actor of Baghdadi-Indian Jewish descent; most well known for playing the role of a Pakistani shop owner, "Bhabu", on Seinfeld, US TV series.

- Silas Aaron Hardoon, real estate tycoon.

- Abraham Hillel, rabbi.

- David and Simon Reuben,[71] tycoons.

- Shelomo Bekhor Hussein, rabbi and publisher.

- Joe Balass, filmmaker

- Lt Gen J. F. R. Jacob, Indian military commander in the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971; former Governor of Goa and Punjab.

- Hakham Ezra Reuben Barook, a High Priest in Jerusalem in 1856; he traveled to India and settled in Calcutta. His name is mentioned in Rabbi Ezekiel Nissim Musleah's book titled "On the banks of the Ganga: The Sojourn of Jews in Calcutta.[2]

- Gerry Judah, artist and designer.

- Tim Judah, journalist and historian.

- Lord Kadoorie

- British Asiansculptor; Baghdadi Jewish mother.

- David Saul Marshall, the first Chief Minister of Singapore.

- Bollywoodactress.

- Bollywoodactress.

- Albert Abdullah David Sassoon, merchant.

- David Sassoon, merchant and founder of the Sassoon family.

- Sassoon David Sassoon, English merchant.

- Gaby Dellal, film director

- Alan Yentob, television presenter and executive

- Samantha Ellis, writer

- Siegfried Sassoon, English poet during World War I, grandson of David Sassoon.[72]

- Abraham Sofaer, actor.

- Marina Benjamin, author

- Jael Silliman, feminist scholar and historian.

- David Mordecai, photographer.

- Khwaja).[73]

- Abraham David Sofaer, former federal judge for the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, Scholar at the Hoover Institute and Legal Adviser to the United States State Department.

- Nahoum Israel Mordecai, founder of Nahoum & Sons bakery, Kolkata, India.

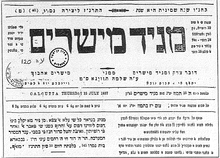

- Shlomo Twena, rabbi, scholar, writer, translator and journalist. Editor of the weekly "Magid Mishri" newspaper

See also

- Jewish ethnic divisions

- Indian Jews

- Jews of Kolkata

- Baghdad Arabic (Jewish)

- David Sassoon

- Asian Jews

- British Asians

- Indian Americans

- Judeo-Malay

References

- ^ Cuinet, Vital (1894). La Turquie d'Asie (in French). Vol. 3. Paris. p. 66. Retrieved Jul 11, 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ISBN 9780815803133– via Google Books.

- ^ "Calcutta", Jewish Virtual Library

- ISBN 965-278-179-7

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84356-002-9.

- ^ "India virtual Jewish tour". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Calcutta Jews", The Forward

- ^ ISBN 978-0-00-812761-9.

- ^ "Rabbi's Message" (PDF). www.kahaljoseph.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2018.

- ^ "Jewish Merchants in the Mughal Empire", Ishrat Ilam, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Vol. 65 (2004), pp. 267–276

- ^ In Antique Land, Amitav Ghosh, 1992, p.19.

- ^ ISBN 9781108139069– via Google Books.

- JSTOR 3622197.

- ^ "Sarmad the Magnificently Naked 17th-Century Jewish Mystic – Tablet Magazine". tabletmag.com. 2016-12-16.

- ^ a b ""The Last Jews in India and Burma" by Nathan Katz and Ellen S. Goldberg". Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ "Recalling Jewish Calcutta | Shalome Aaron Cohen, Founding family member · 03 Notable Members of and from the Community". Archived from the original on 2018-07-08. Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ a b Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus (1916). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk and Wagnalls.

- ISBN 9789004354012.

- ISBN 9781851098736.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Baghdadi Jews of India".

- ^ Abraham, Isaac Silas (21 July 1969). "The Origin and History of the Calcutta Jews". Daw Sen – via Google Books.

- ^ "Passover in Baghdad". 1 July 2003.

- ^ "Aleppo". jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ "The Jewish Community of Mashhad". Museum of The Jewish People – Beit Hatfutsot':'בית התפוצות - מוזיאון העם היהודי'. Archived from the original on 2020-09-20. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ^ "מסעי ישראל-בלשון אנגלית". issuu. 5 September 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0300095470– via Google Books.

- ^ Benjamin, J. (1859). Eight Years in Asia and Africa: From 1846 to 1855. Published by the Author. p.118.

- ^ ""The Last Jews in India and Burma" by Nathan Katz and Ellen S. Goldberg". www.jcpa.org.

- ^ "Jewish Cemetery in Kolkata/Calcutta", Rangandatta blog

- ^ a b c "Calcutta". jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ a b c d "Shodhganga : a reservoir of Indian theses @ INFLIBNET" (PDF).

- ^ a b "The Jewish Community of Mumbai-Bombay". Museum of The Jewish People – Beit Hatfutsot':'בית התפוצות - מוזיאון העם היהודי'. Archived from the original on 2018-07-08. Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ "Mumbai". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ ISBN 9780739116470– via Google Books.

- ^ "EIGHT YEARSI NASIA AND AFRICAFROM 1846 TO 1855". issuu. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- ^ ISBN 9780739116470.

- ISBN 9788174786852– via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84980-632-9.

- ^ ISBN 9780739116470– via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Marks, Zach (2013-10-24). "The Last Jews of Kolkata". New York Times.

- ISBN 9783631575338– via Google Books.

- ^ "A case study of the Jewish Diaspora in Penang (1830s-1970s)" (PDF).

- ISBN 9781482851601– via Google Books.

- ^ a b c "The Jews of Kobe". xenon.stanford.edu.

- ISBN 9781482851601– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9789385714535.

- ^ ISBN 9789385714535– via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 9780739116470– via Google Books.

- S2CID 145588515.

- ^ ISBN 9789004354012– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781498551755– via Google Books.

- S2CID 145597159.

- ^ Weil, S. 2019 (ed.) The Baghdadi Jews in India: Maintaining Communities, Negotiating Identities and Creating Super-Diversity, London and New York: Routledge.

- ^ ISBN 9789004289109– via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 9789652781796– via Google Books.

- ^ Levy, Lital (October 2010). "Mevasser (Calcutta)". Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World.

- ^ a b "Recalling Jewish Calcutta | Hacham Twena · 03 Notable Members of the Community". Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ^ "A Note on Jewish Weddings" Archived 2018-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Calcutta

- ISBN 9781851098736– via Google Books.

- ^ "Rahmo_Sassoon – Jewish Community of Kansai (Kobe City, Japan)". jcckobe.org.

- ^ Kamin, Debra (2012-04-03). "A Childhood Passage to Israel for Baghdadi Jews of India" (Blog).

- ^ "Recalling Jewish Calcutta". jewishcalcutta.in.

- Rangoon and Pathein both elected Baghdadi Jewish mayors and the population peaked at 2500 Jews in the 1930s. https://books.google.com/books?id=PVCzxtaSCXAC&pg=PR8

- ^ Green, David B. (12 March 2015). "This Day in Jewish History 1908: The Iraqi Jew Who Would Lead Singapore Is Born". Haaretz.

- ^ "The Sum of His Many Parts". OPEN Magazine. June 2012.

- ^ "About Our History" Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, Ohealleah

- ^ "HOME". singaporejews.com.

- ^ "Jewish artist Gerry Judah and the St Paul's crucifix". thejc.com. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- ^ Cooper, Judy and John Cooper. "The Life-Cycle of Baghdadi Jews of India", in India's Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art and Life-Cycle, (ed) Shalva Weil, Mumbai: Marg Publications [first published in 2002; 3rd edn.], 2009. pp. 100–109.

- ^ "The Jews of Penang". Penang Story. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Johari, Aarefa (26 April 2016). "In photos: The Mumbai Baghdadi Jewish community that produced the brothers who topped UK's rich list".

- ^ Weil, S. 2022b. “Siegfried Sassoon and the Sassoons”.Clare Hall Review, pp. 52-3.

- JSTOR 44144740.

External links

- "Baghdadi Jewish Community". Iraqi Jewish Archives. USA: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- Indian Jews – Jewish Encyclopedia

- Calcutta Jews – Jewish Encyclopedia