Disinformation

It has been suggested that Disinformation attack be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since October 2023. |

| Part of a series on |

| War Outline |

|---|

|

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to

In contrast, misinformation refers to inaccuracies that stem from inadvertent error.[6] Misinformation can be used to create disinformation when known misinformation is purposefully and intentionally disseminated.[7] "Fake news" has sometimes been categorized as a type of disinformation, but scholars have advised not using these two terms interchangeably or using "fake news" altogether in academic writing since politicians have weaponized it to describe any unfavorable news coverage or information.[8]

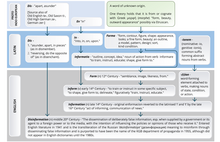

Etymology

The English word disinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix dis- to information making the meaning "reversal or removal of information". The rarely used word had appeared with this usage in print at least as far back as 1887.[10][11][12][13]

Some consider it a

Disinformation first made an appearance in dictionaries in 1985, specifically, Webster's New College Dictionary and the American Heritage Dictionary.

By 1990, use of the term disinformation had fully established itself in the English language within the lexicon of politics.[18] By 2001, the term disinformation had come to be known as simply a more civil phrase for saying someone was lying.[19] Stanley B. Cunningham wrote in his 2002 book The Idea of Propaganda that disinformation had become pervasively used as a synonym for propaganda.[20]

Operationalization

The Shorenstein Center at Harvard University defines disinformation research as an academic field that studies “the spread and impacts of misinformation, disinformation, and media manipulation,” including “how it spreads through online and offline channels, and why people are susceptible to believing bad information, and successful strategies for mitigating its impact”[21] According to a 2023 research article published in New Media & Society,[4] disinformation circulates on social media through deception campaigns implemented in multiple ways including: astroturfing, conspiracy theories, clickbait, culture wars, echo chambers, hoaxes, fake news, propaganda, pseudoscience, and rumors.

In order to distinguish between similar terms, including misinformation and malinformation, scholars collectively agree on the definitions for each term as follows: (1) disinformation is the strategic dissemination of false information with the intention to cause public harm;[22] (2) misinformation represents the unintentional spread of false information; and (3) malinformation is factual information disseminated with the intention to cause harm,[23][24] these terms are abbreviated 'DMMI'.[25]

In 2019, Camille François devised the "ABC" framework of understanding different modalities of online disinformation:

- Manipulative Actors, who "engage knowingly and with clear intent in viral deception campaigns" that are "covert, designed to obfuscate the identity and intent of the actor orchestrating them." Examples include personas such as Guccifer 2.0, Internet trolls, state media, and military operatives.

- Deceptive Behavior, which "encompasses the variety of techniques viral deception actors may use to enhance and exaggerate the reach, virality and impact of their campaigns." Examples include Internet bots, astroturfing, and "paid engagement".

- Harmful Content, which includes

In 2020, the Brookings Institution proposed amending this framework to include Distribution, defined by the "technical protocols that enable, constrain, and shape user behavior in a virtual space".[27] Similarly, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace proposed adding Degree ("distribution of the content ... and the audiences it reaches") and Effect ("how much of a threat a given case poses").[28]

Comparisons with propaganda

Whether and to what degree disinformation and propaganda overlap is subject to debate. Some (like

Practice

Disinformation is the label often given to foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI).[31][32] Studies on disinformation are often concerned with the content of activity whereas the broader concept of FIMI is more concerned with the "behaviour of an actor" that is described through the military doctrine concept of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs).[31]

Disinformation is primarily carried out by government

Worldwide

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2023) |

Soviet disinformation

Russian disinformation

Russian disinformation campaigns have occurred in many countries.[39][40][41][42] For example, disinformation campaigns led by Yevgeny Prigozhin have been reported in several African countries.[43][44] Russia, however, denies that it uses disinformation to influence public opinion.[45]

Often Russian campaigns aim to disrupt domestic politics within Europe and the United States in an attempt to weaken the West and shift the balance of world power to Russia and her allies. Russia according to VOA seeks to promote American isolationism, border security concerns and racial tensions within the United States through its disinformation campaigns.[46][47][48]American disinformation

The

In October 1986, the term gained increased currency in the U.S. when it was revealed that two months previously, the Reagan Administration had engaged in a disinformation campaign against then-leader of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi.[51] White House representative Larry Speakes said reports of a planned attack on Libya as first broken by The Wall Street Journal on August 25, 1986, were "authoritative", and other newspapers including The Washington Post then wrote articles saying this was factual.[51] U.S. State Department representative Bernard Kalb resigned from his position in protest over the disinformation campaign, and said: "Faith in the word of America is the pulse beat of our democracy."[51]

The executive branch of the Reagan administration kept watch on disinformation campaigns through three yearly publications by the Department of State: Active Measures: A Report on the Substance and Process of Anti-U.S. Disinformation and Propaganda Campaigns (1986); Report on Active Measures and Propaganda, 1986–87 (1987); and Report on Active Measures and Propaganda, 1987–88 (1989).[49]

Response

Responses from cultural leaders

Pope Francis condemned disinformation in a 2016 interview, after being made the subject of a fake news website during the 2016 U.S. election cycle which falsely claimed that he supported Donald Trump.[52][53][54] He said the worst thing the news media could do was spread disinformation. He said the act was a sin,[55][56] comparing those who spread disinformation to individuals who engage in coprophilia.[57][58]

Ethics in warfare

In a contribution to the 2014 book Military Ethics and Emerging Technologies, writers David Danks and Joseph H. Danks discuss the ethical implications in using disinformation as a tactic during

Research

Research related to disinformation studies is increasing as an applied area of inquiry.[60][61] The call to formally classify disinformation as a cybersecurity threat is made by advocates due to its increase in social networking sites.[62] Researchers working for the University of Oxford found that over a three-year period the number of governments engaging in online disinformation rose from 28 in 2017, to 40 in 2018, and 70 in 2019. Despite the proliferation of social media websites, Facebook and Twitter showed the most activity in terms of active disinformation campaigns. Techniques reported on included the use of bots to amplify hate speech, the illegal harvesting of data, and paid trolls to harass and threaten journalists.[63]

Whereas disinformation research focuses primarily on how actors orchestrate deceptions on social media, primarily via fake news, new research investigates how people take what started as deceptions and circulate them as their personal views.[5] As a result, research shows that disinformation can be conceptualized as a program that encourages engagement in oppositional fantasies (i.e., culture wars), through which disinformation circulates as rhetorical ammunition for never-ending arguments.[5] As disinformation entangles with culture wars, identity-driven controversies constitute a vehicle through which disinformation disseminates on social media. This means that disinformation thrives, not despite raucous grudges but because of them. The reason is that controversies provide fertile ground for never-ending debates that solidify points of view.[5]

Scholars have pointed out that disinformation is not only a foreign threat as domestic purveyors of disinformation are also leveraging traditional media outlets such as newspapers, radio stations, and television news media to disseminate false information.[64] Current research suggests right-wing online political activists in the United States may be more likely to use disinformation as a strategy and tactic.[65] Governments have responded with a wide range of policies to address concerns about the potential threats that disinformation poses to democracy, however, there is little agreement in elite policy discourse or academic literature as to what it means for disinformation to threaten democracy, and how different policies might help to counter its negative implications.[66]

Consequences of exposure to disinformation online

There is a broad consensus amongst scholars that there is a high degree of disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda online; however, it is unclear to what extent such disinformation has on political attitudes in the public and, therefore, political outcomes.[67] This conventional wisdom has come mostly from investigative journalists, with a particular rise during the 2016 U.S. election: some of the earliest work came from Craig Silverman at Buzzfeed News.[68] Cass Sunstein supported this in #Republic, arguing that the internet would become rife with echo chambers and informational cascades of misinformation leading to a highly polarized and ill-informed society.[69]

Research after the 2016 election found: (1) for 14 percent of Americans social media was their "most important" source of election news; 2) known false news stories "favoring Trump were shared a total of 30 million times on Facebook, while those favoring Clinton were shared 8 million times"; 3) the average American adult saw fake news stories, "with just over half of those who recalled seeing them believing them"; and 4) people are more likely to "believe stories that favor their preferred candidate, especially if they have ideologically segregated social media networks."[70] Correspondingly, whilst there is wide agreement that the digital spread and uptake of disinformation during the 2016 election was massive and very likely facilitated by foreign agents, there is an ongoing debate on whether all this had any actual effect on the election. For example, a double blind randomized-control experiment by researchers from the London School of Economics (LSE), found that exposure to online fake news about either Trump or Clinton had no significant effect on intentions to vote for those candidates. Researchers who examined the influence of Russian disinformation on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential campaign found that exposure to disinformation was (1) concentrated among a tiny group of users, (2) primarily among Republicans, and (3) eclipsed by exposure to legitimate political news media and politicians. Finally, they find "no evidence of a meaningful relationship between exposure to the Russian foreign influence campaign and changes in attitudes, polarization, or voting behavior."[71] As such, despite its mass dissemination during the 2016 Presidential Elections, online fake news or disinformation probably did not cost Hillary Clinton the votes needed to secure the presidency.[72]

Research on this topic is continuing, and some evidence is less clear. For example, internet access and time spent on social media does not appear correlated with polarisation.[73] Further, misinformation appears not to significantly change political knowledge of those exposed to it.[74] There seems to be a higher level of diversity of news sources that users are exposed to on Facebook and Twitter than conventional wisdom would dictate, as well as a higher frequency of cross-spectrum discussion.[75][76] Other evidence has found that disinformation campaigns rarely succeed in altering the foreign policies of the targeted states.[77]

Research is also challenging because disinformation is meant to be difficult to detect and some social media companies have discouraged outside research efforts.[78] For example, researchers found disinformation made "existing detection algorithms from traditional news media ineffective or not applicable...[because disinformation] is intentionally written to mislead readers...[and] users' social engagements with fake news produce data that is big, incomplete, unstructured, and noisy."[78] Facebook, the largest social media company, has been criticized by analytical journalists and scholars for preventing outside research of disinformation.[79][80][81][82]

Alternative perspectives and critiques

Researchers have criticized the framing of disinformation as being limited to technology platforms, removed from its wider political context and inaccurately implying that the media landscape was otherwise well-functioning.[83] "The field possesses a simplistic understanding of the effects of media technologies; overemphasizes platforms and underemphasizes politics; focuses too much on the United States and Anglocentric analysis; has a shallow understanding of political culture and culture in general; lacks analysis of race, class, gender, and sexuality as well as status, inequality, social structure, and power; has a thin understanding of journalistic processes; and, has progressed more through the exigencies of grant funding than the development of theory and empirical findings."[84]

Alternative perspectives have been proposed:

- Moving beyond fact-checking and media literacy to study a pervasive phenomenon as something that involves more than news consumption.

- Moving beyond technical solutions including AI-enhanced fact checking to understand the systemic basis of disinformation.

- Develop a theory that goes beyond Americentrism to develop a global perspective, understand cultural imperialism and Third World dependency on Western news,[85] and understand disinformation in the Global South.[86]

- Develop market-oriented disinformation research that examines the financial incentives and business models that nudge content creators and digital platforms to circulate disinformation online.[4]

- Include a multidisciplinary approach, involving feminist studies, and science and technology studies.

- Develop understandings of Gendered-based disinformation (GBD) defined as "the dissemination of false or misleading information attacking women (especially political leaders, journalists and public figures), basing the attack on their identity as women."[87][88]

Strategies for spreading disinformation

Disinformation attack

The research literature on how disinformation spreads is growing.[67] Studies show that disinformation spread in social media can be classified into two broad stages: seeding and echoing.[5] "Seeding," when malicious actors strategically insert deceptions, like fake news, into a social media ecosystem, and "echoing" is when the audience disseminates disinformation argumentatively as their own opinions often by incorporating disinformation into a confrontational fantasy.

Internet manipulation

Studies show four main methods of seeding disinformation online:[67]

- Selective censorship

- Manipulation of search rankings

- Hacking and releasing

- Directly Sharing Disinformation

See also

- Active Measures Working Group

- Agitprop

- Black propaganda

- Censorship

- Chinese information operations and information warfare

- Counter Misinformation Team

- COVID-19 misinformation

- Deepfakes

- Demoralization (warfare)

- Denial and deception

- Disinformation attack

- Disinformation in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Fake news

- False flag

- Fear, uncertainty and doubt

- Gaslighting

- Internet manipulation

- Knowledge falsification

- Kompromat

- Manufacturing Consent

- Media manipulation

- Military deception

- Post-truth politics

- Propaganda in the Soviet Union

- Sharp power

- Social engineering (political science)

- The Disinformation Project

Notes

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-936488-60-5

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-031572-0

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-031573-7

- ^ S2CID 264816011– via SAGE.

- ^ from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Ireton, C & Posetti, J (2018) "Journalism, fake news & disinformation: handbook for journalism education and training" UNESCO". Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-84800-355-2

- from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ a b Hadley, Newman (2022). "Author". Journal of Information Warfare. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

Strategic communications advisor working across a broad range of policy areas for public and multilateral organisations. Counter-disinformation specialist and published author on foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI).

- ^ "City & County Cullings (Early use of the word "disinformation" 1887)". Medicine Lodge Cresset. 17 February 1887. p. 3. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Professor Young on Mars and disinformation (1892)". The Salt Lake Herald. 18 August 1892. p. 4. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Pure nonsense (early use of the word disinformation) (1907)". The San Bernardino County Sun. 26 September 1907. p. 8. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Support for Red Cross helps U.S. boys abroad, Rotary Club is told (1917)". The Sheboygan Press. 18 December 1917. p. 4. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-0898-6,

In fact, the word disinformation is a cognate for the Russian dezinformatsia, taken from the name of a division of the KGB devoted to black propaganda.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, Adam (26 November 2016), "Before 'fake news,' there was Soviet 'disinformation'", The Washington Post, archived from the original on 14 May 2019, retrieved 3 December 2016

- ^ a b Jackson, Dean (2018), DISTINGUISHING DISINFORMATION FROM PROPAGANDA, MISINFORMATION, AND "FAKE NEWS" (PDF), National Endowment for Democracy, archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2022, retrieved 31 May 2022

- ISBN 978-0-08-034939-8

- ISBN 978-0-15-180704-8

- ISBN 978-0-435-10960-8

- ISBN 978-0-275-97445-9

- ^ "Disinformation". Shorenstein Center. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Center for Internet Security. (3 October 2022). "Essential Guide to Election Security:Managing Mis-, Dis-, and Malinformation". CIS website Archived 18 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Baines, Darrin; Elliott, Robert J. R. (April 2020). "Defining misinformation, disinformation and malinformation: An urgent need for clarity during the COVID-19 infodemic". Discussion Papers. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making". Council of Europe Publishing. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Newman, Hadley. "Understanding the Differences Between Disinformation, Misinformation, Malinformation and Information – Presenting the DMMI Matrix". Draft Online Safety Bill (Joint Committee). UK: UK Government. Archived from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ François, Camille (20 September 2019). "Actors, Behaviors, Content: A Disinformation ABC - Highlighting Three Vectors of Viral Deception to Guide Industry & Regulatory Responses" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Alaphilippe, Alexandre (27 April 2020). "Adding a 'D' to the ABC disinformation framework". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Pamment, James (2020). The ABCDE Framework (PDF) (Report). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. pp. 5–9. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024.

- ^ Can public diplomacy survive the internet? (PDF), May 2017, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2019

- ^ The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money (PDF), Institute of Modern Russia, 2014, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2019

- ^ ISBN 978-952-7472-46-0. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022 – via European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ European Extrernal Action Service (EEAS) (27 October 2021). "Tackling Disinformation, Foreign Information Manipulation & Interference".

- ISBN 978-0-8108-5641-7

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-81681-6

- S2CID 202281476.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (26 November 2016), "Before 'fake news,' there was Soviet 'disinformation'", The Washington Post, retrieved 3 December 2016

- ISBN 978-0-313-29605-5

- ISBN 978-1610690713

- S2CID 247038589. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- JSTOR 26623066.

- ^ Anne Applebaum; Edward Lucas (6 May 2016), "The danger of Russian disinformation", The Washington Post, retrieved 9 December 2016

- ^ "Russian state-sponsored media and disinformation on Twitter". ZOiS Spotlight. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Russian Disinformation Is Taking Hold in Africa". CIGI. 17 November 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

The Kremlin's effectiveness in seeding its preferred vaccine narratives among African audiences underscores its wider concerted effort to undermine and discredit Western powers by pushing or tapping into anti-Western sentiment across the continent.

- ^ "Leaked documents reveal Russian effort to exert influence in Africa". The Guardian. 11 June 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

The mission to increase Russian influence on the continent is being led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a businessman based in St Petersburg who is a close ally of the Russian president, Vladimir Putin. One aim is to 'strong-arm' the US and the former colonial powers the UK and France out of the region. Another is to see off 'pro-western' uprisings, the documents say.

- ^ MacFarquharaug, Neil (28 August 2016), "A Powerful Russian Weapon: The Spread of False Stories", The New York Times, p. A1, retrieved 9 December 2016,

Moscow adamantly denies using disinformation to influence Western public opinion and tends to label accusations of either overt or covert threats as 'Russophobia.'

- ^ "How Russia's disinformation campaign seeps into US views". Voice of America. 11 April 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Belton, Catherine (17 April 2024). "Secret Russian foreign policy document urges action to weaken the U.S." The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-29605-5

- ISBN 978-0-670-82825-8

- ^ ISBN 978-1-133-31138-6

- ^ "Pope Warns About Fake News-From Experience", The New York Times, Associated Press, 7 December 2016, archived from the original on 7 December 2016, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Alyssa Newcomb (15 November 2016), "Facebook, Google Crack Down on Fake News Advertising", NBC News, NBC News, archived from the original on 6 April 2019, retrieved 16 November 2016

- ^ Schaede, Sydney (24 October 2016), "Did the Pope Endorse Trump?", FactCheck.org, archived from the original on 19 April 2019, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Pullella, Philip (7 December 2016), "Pope warns media over 'sin' of spreading fake news, smearing politicians", Reuters, archived from the original on 23 November 2020, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ "Pope Francis compares fake news consumption to eating faeces", The Guardian, 7 December 2016, archived from the original on 7 March 2021, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Zauzmer, Julie (7 December 2016), "Pope Francis compares media that spread fake news to people who are excited by feces", The Washington Post, archived from the original on 4 February 2021, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (7 December 2016), "Pope Francis: Fake news is like getting sexually aroused by faeces", The Independent, archived from the original on 26 January 2021, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-73710-4

- ^ Spies, Samuel (14 August 2019). "Defining "Disinformation", V1.0". MediaWell, Social Science Research Council. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- S2CID 201392983.

- S2CID 218651389.

- ^ "Samantha Bradshaw & Philip N. Howard. (2019) The Global Disinformation Disorder: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. Working Paper 2019.2. Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda" (PDF). comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "This Analysis Shows How Viral Fake Election News Stories Outperformed Real News On Facebook". BuzzFeed News. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- )

- S2CID 32730475.

- PMID 36624094.

- S2CID 218592685.

- PMID 28928150.

- ISSN 0895-3309.

- S2CID 206632821.

- S2CID 18865773.

- S2CID 211312944.

- ^ from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Edelson, Laura; McCoy, Damon. "How Facebook Hinders Misinformation Research". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Edelson, Laura; McCoy, Damon (14 August 2021). "Facebook shut down our research into its role in spreading disinformation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- doi:10.37016/mr-2020-76. Archived from the originalon 15 October 2023.

- ^ "What Comes After Disinformation Studies?". Center for Information, Technology, & Public Life (CITAP), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Tworek, Heidi (2 August 2022). "Can We Move Beyond Disinformation Studies?". Centre for International Governance Innovation. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-119-71444-6.

- ^ Sessa, Maria Giovanna (4 December 2020). "Misogyny and Misinformation: An analysis of gendered disinformation tactics during the COVID-19 pandemic". EU DisinfoLab. Archived from the original on 19 September 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Sessa, Maria Giovanna (26 January 2022). "What is Gendered Disinformation?". Heinrich Böll Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-0190931414.

- S2CID 264816011.

- ^ Marchal, Nahema; Neudert, Lisa-Maria (2019). "Polarisation and the use of technology in political campaigns and communication" (PDF). European Parliamentary Research Service.

- S2CID 258125103.

- S2CID 248934562.

- S2CID 264474368.

- ISBN 9780745695792. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Condemnation over Egypt's internet shutdown". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Net neutrality wins in Europe – a victory for the internet as we know it". ZME Science. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-0-08-031572-0

- Boghardt, Thomas (26 January 2010), "Operation INFEKTION – Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign" (PDF), Studies in Intelligence, 53 (4), retrieved 9 December 2016

- ISBN 978-0-396-08194-4

- O'Connor, Cailin, and James Owen Weatherall, "Why We Trust Lies: The most effective misinformation starts with seeds of truth", Scientific American, vol. 321, no. 3 (September 2019), pp. 54–61.

- ISBN 978-1-936488-60-5

- Fletcher Schoen; Christopher J. Lamb (1 June 2012), "Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic. Communications: How One Interagency Group. Made a Major Difference" (PDF), Strategic Perspectives, 11, retrieved 9 December 2016

- ISBN 978-0080315737

- Taylor, Adam (26 November 2016), "Before 'fake news,' there was Soviet 'disinformation'", The Washington Post, retrieved 3 December 2016

- Legg, Heidi; Kerwin, Joe (1 November 2018), The Fight Against Disinformation in the U.S.: A Landscape Analysis, Harvard Kennedy School, Shorenstein Center, retrieved 10 August 2020

External links

- Disinformation Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine – a learning resource from the British Library including an interactive movie and activities.

- MediaWell – an initiative of the nonprofit Social Science Research Council seeking to track and curate disinformation, misinformation, and fake news research.