Visual arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

| History of art |

|---|

The visual arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas encompasses the visual artistic practices of the

Indigenous American visual arts include portable arts, such as painting, basketry, textiles, or photography, as well as monumental works, such as architecture, land art, public sculpture, or murals. Some Indigenous art forms coincide with Western art forms; however, some, such as porcupine quillwork or birchbark biting are unique to the Americas.

Indigenous art of the Americas has been collected by Europeans since sustained contact in 1492 and joined collections in cabinets of curiosities and early museums. More conservative Western art museums have classified Indigenous art of the Americas within arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, with precontact artwork classified as pre-Columbian art, a term that sometimes refers to only precontact art by Indigenous peoples of Latin America. Native scholars and allies are striving to have Indigenous art understood and interpreted from Indigenous perspectives.

Lithic and Archaic stage

The

Belonging in the lithic stage, the oldest known art in the Americas is a fossilized megafauna bone, possibly from a mammoth, carved with a profile of walking mammoth or mastodon that dates back to 11,000 BCE.[1] The bone was found early in the 21st century near Vero Beach, Florida, in an area where human bones (Vero man) had been found in association with extinct pleistocene animals early in the 20th century. The bone is too mineralized to be dated, but the carving has been authenticated as having been made before the bone became mineralized. The anatomical correctness of the carving and the heavy mineralization of the bone indicate that the carving was made while mammoths and/or mastodons still lived in the area, more than 10,000 years ago.[2][3][4][5]

The oldest known painted object in North America is the

The southwestern United States and certain regions of the Andes have the highest concentration of

-

A petroglyph of a caravan of bighorn sheep near Moab, Utah, United States; a common theme in glyphs from the southwestern desert

-

Archaic abstract curvilinear style petroglyphs, Coso Rock Art District, California

-

Petroglyph from Columbia River Gorge, Washington, United States

North America

Arctic

The

- Inuit art from Alaska, Canada, and Greenland

-

Iñupiaq, 1905–1978), Alaska; Honolulu Museum of Art(Hawaii, USA)

-

Musée du quai Branly(Paris)

-

Toy Angakkuq (shaman); 6 February 1998;caribou bone & feathers; by Palaya Qiatsuq

Subarctic

Cultures of interior Alaska and Canada living south of the

-

21st-centuryAthabaskan moosehair tufting on beaded hide box,

Fairbanks, Alaska -

Tsuu T'ina painted hide tipi,, Canada

Alberta -

Man's hide jacket. The floral designs' stems feature "thorny" beadwork, typical of the Subarctic, Museum of Anthropology at UBC

Northwest Coast

The art of the

-

ATlingitstyle

-

'Namgis thunderbird transformation mask, 19th century, cedar, pigments, leather, nails, metal plate, 71 in. wide when open, Brooklyn Museum, NY

-

Haida argillite carving; 1850–1900; from Haida Gwaii; National Museum of the American Indian

-

Cedar bark hat;Museum of the Americas (Madrid, Spain)

Eastern Woodlands

Northeastern Woodlands

The

The Woodland period (1000 BCE–1000 CE) is divided into early, middle, and late periods, and consisted of cultures that relied mostly on hunting and gathering for their subsistence. Ceramics made by the Deptford culture (2500 BCE–100 CE) are the earliest evidence of an artistic tradition in this region. The Adena culture are another well-known example of an early Woodland culture. They carved stone tablets with zoomorphic designs, created pottery, and fashioned costumes from animal hides and antlers for ceremonial rituals. Shellfish was a mainstay of their diet, and engraved shells have been found in their burial mounds.

The

The

From the 12th century onward, the

Iroquois people carve

- Art from the Eastern woodlands of North America

-

Hopewell mounds from the Mound City Group in Ohio

-

Carved soapstone pipe depicting a raven, Hopewell tradition

-

Copper falcon from the Mound City Group site of the Hopewell culture

-

One fine art sculptor of the mid-nineteenth century was

Native peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands continued to make visual art through the 20th and 21st centuries. One such artist is Sharol Graves, whose serigraphs have been exhibited in the National Museum of the American Indian.[16] Graves is also the illustrator of The People Shall Continue from Lee & Low Books.

Southeastern Woodlands

The

-

Clay cooking utensils, Poverty Point

-

Clay female figurines, Poverty Point

-

Carved gorgets andatlatlweights, Poverty Point

The

-

Engraved shell gorget, Spiro Mounds (Mississippian culture)

-

Engraved stone palette, Moundville Site, back used for mixing paint (Mississippian culture)

-

Stone effigies, Etowah Site (Mississippian culture)

-

Ceramic underwater panther jug, Rose Mound (Mississippian culture)

A large number of pre-Columbian wooden artifacts have been found in Florida. While the oldest wooden artifacts are as much as 10,000 years old, carved and painted wooden objects are known only from the past 2,000 years. Animal effigies and face masks have been found at a number of sites in Florida. Animal effigies dating to between 200 and 600 were found in a mortuary pond at Fort Center, on the west side of Lake Okeechobee. Particularly impressive is a 66 cm tall carving of an eagle.[20]

More than 1,000 carved and painted wooden objects, including masks, tablets, plaques and effigies, were excavated in 1896 at

The

-

Eagle totem, Fort Center, Florida

-

Alligator effigy, wood carving, Key Marco, Florida

-

Wooden mask, Key Marco, Florida

-

Seminole patchwork fringed dance shawl, Big Cypress Indian Reservation, Florida, 1980s

The West

Great Plains

Tribes have lived on the

In the Plains Village period, the cultures of the area settled in enclosed clusters of rectangular houses and cultivated maize. Various regional differences emerged, including Southern Plains, Central Plains, Oneota, and Middle Missouri. Tribes were both nomadic hunters and semi-nomadic farmers. During the Plains Coalescent period (1400-European contact) some change, possibly drought, caused the mass migration of the population to the Eastern Woodlands region, and the Great Plains were sparsely populated until pressure from American settlers drove tribes into the area again.

The advent of the horse revolutionized the cultures of many historical Plains tribes. Horse culture enabled tribes to live a completely nomadic existence, hunting buffalo. Buffalo hide clothing was decorated with porcupine quill embroidery and beads – dentalium shells and elk teeth were prized materials. Later coins and glass beads acquired from trading were incorporated into Plains art. Plains beadwork has flourished into contemporary times.

Buffalo was the preferred material for Plains hide painting. Men painted narrative, pictorial designs recording personal exploits or visions. They also painted pictographic historical calendars known as Winter counts. Women painted geometric designs on tanned robes and rawhide parfleches, which sometimes served as maps.[25]

During the Reservation Era of the late 19th century, buffalo herds were systematically destroyed by non-native hunters. Due to the scarcity of hides, Plains artists adopted new painting surfaces, such as muslin or paper, giving birth to Ledger art, so named for the ubiquitous ledger books used by Plains artists.

-

Sioux dress with fully beaded yoke.

-

Sioux beaded and painted rawhide parfleches.

-

Ledger drawing ofHaokah (c. 1880) by Black Hawk (Lakota).

-

Kiowa ledger art, possibly of the 1874 Buffalo Wallow battle, Red River War.

Great Basin and Plateau

Since the archaic period the Plateau region, also known as the

-

Nez Percebag with contour beadwork, c. 1850-60

-

Nez Perce man's beaded and quilled buckskin shirt with eagle feathers and ermine pelts, c. 1880-85

-

Shoshone beaded men's moccasins, circa 1900, Wyoming

-

Basket byMono Lake Paiute), California, 30" diam., c. 1931-35

California

The Native Americans of California have used different mediums and forms for their traditional designs found in artifacts that express their history and culture. Some traditional art forms and archaeological evidence include basketry, painted pictographs and petroglyphs found on the walls in the caves, and effigy figurines.

The

California has a large number of

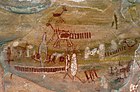

The most elaborate pictographs in the U.S are considered to be the

An art practice used by the Native American tribes of California, such as the Chumash, are carving and shaping effigy figurines. From multiple archaeological studies that occurred in various historical sites (the Channel Islands, Malibu, Santa Barbara, and more) many effigy figures were discovered and portrayed several zoomorphic forms, such as fish, whales, frogs, and birds.[30][31] As a result from analyzing these effigy figurines in these studies, several strong conclusions were drawn that provided context to the Native Americans of California, such as social attributes between the Chumash and other tribes, economical significance, and possibly used in rituals.[30][31][32] Some effigy figurines were found in burials, and others were found in relation to having similar stylistic features with dates that suggest social interactional spheres in the MIddle and Late Holocene between tribes.[30][31]

-

Chumash rock artat Painted Cave

-

A basket made by thePomo peopleof northern California.

-

Pomo beaded, coiled basket, sedgeroot, willow, glass beads, abalone, circa 1880

-

Late 19th-century Hupa woman's cap, bear grass and conifer root, Stanford University

Southwest

In the Southwestern United States numerous pictographs and petroglyphs were created. The

The

For hundreds of years, Ancestral Pueblo created utilitarian grayware and black-on-white pottery and occasionally orange or red ceramics. In historical times, Hopi created ollas, dough bowls, and food bowls of different sizes for daily use, but they also made more elaborate ceremonial mugs, jugs, ladles, seed jars and those vessels for ritual use, and these were usually finished with polished surfaces and decorated with black painted designs. At the turn of the 20th century, Hopi potter Nampeyo famous revived Sikyátki-style pottery, originated on First Mesa in the 14th to 17th centuries.[33]

Southwest architecture includes

Turquoise, jet, and spiny oyster shell have been traditionally used by Ancestral Pueblo for jewelry, and they developed sophisticated inlay techniques centuries ago.

Around 200 CE the

Within the last millennium,

In the 1850s, Navajos adopted silversmithing from the Mexicans. Atsidi Sani (Old Smith) was the first Navajo silversmith, but he had many students, and the technology quickly spread to surrounding tribes. Today thousands of artists produce silver jewelry with turquoise. Hopi are renowned for their overlay silver work and cottonwood carvings. Zuni artists are admired for their cluster work jewelry, showcasing turquoise designs, as well as their elaborate, pictorial stone inlay in silver.

-

Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, c. 700 CE–1100 CE

-

Navajo Sandpainting.

Mesoamerica and Central America

The cultural development of ancient Mesoamerica was generally divided along east and west. "Archaeologists have dated human presence in Mesoamerica to possibly as early as 21,000 BCE" (Jeff Wallenfeldt)[35]. The stable Maya culture was most dominant in the east, especially the Yucatán Peninsula, while in the west more varied developments took place in subregions. These included West Mexican (1000–1), Teotihuacan (1–500), Mixtec (1000–1200), and Aztec (1200–1521).

Central American civilizations generally lived to the regions south of modern-day Mexico, although there was some overlap between the places.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica was home to the following cultures, among others:

Olmec

The Olmec (1500–400 BCE), who lived on the gulf coast, were the

The most famous artistic creations of the Olmec are colossal basalt heads, believed to be portraits of rulers that were erected to advertise their great power. The Olmec also sculpted votive figurines that they buried beneath the floors of their houses for unknown reasons. These were most often modeled in terracotta, but also occasionally carved from jade or serpentine.

-

Monument 1, one of the four Olmec colossal heads at La Venta. This one is nearly 3 metres (9 ft) tall.

-

An "elongated man" figurine, dark green serpentine.

-

Kunz Axe; 1200-400 BCE; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)[36]

-

Jade mask; 10th–6th century BCE; jadeite; height: 17.1 cm (63⁄4 in.), width: 16.5 (65⁄16 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Teotihuacan

-

A mural showing what has been identified as the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan

-

Restored Teotihuacan architecture showing typical Mesoamerican use of red paint complemented on gold and jade decoration upon marble and granite

-

Mask with a necklace with 55 beads and pendant; serpentine inlaid with amazonite, turquoise, shell, coral and obsidian, 8 in. H, National Museum of Anthropology

-

Statue of Chalchiuhtlicue; National Museum of Anthropology

Classic Veracruz Culture

In his 1957 book on Mesoamerican art, Miguel Covarrubias speaks of Remojadas' "magnificent hollow figures with expressive faces, in majestic postures and wearing elaborate paraphernalia indicated by added clay elements."[37]

-

A large terracotta figurine of a young chieftain in the Remojadas style. 300–600 CE; Height: 31 in (79 cm).

-

Male-female duality figure from Remojadas, 200–500 CE. Note the feminine breast and birds on the right side of the figure.

-

Veracruz altar urn

-

Stone head of a woman from El Tajin

Zapotec

"The Bat God was one of the important deities of the Maya, many elements of whose religion were shared also by the Zapotec. The Bat God in particular is known to have been revered also by the Zapotec ... He was especially associated ... with the underworld."[attribution needed][38] An important Zapotec center was Monte Albán, in present-day Oaxaca, Mexico. The Monte Albán periods are divided into I, II, and III, which range from 200 BCE to 600 CE.

-

Ceramic urn, 200 BCE – 800 CE, British Museum.[39]

-

Ceramic Zapotec vessel

-

Golden ornamentation worn by Zapotec government officials

-

Mosaic mask that represents a Bat god, 25 pieces of jade, with yellow eyes made of shell. It was found in a tomb at Monte Albán

Maya

The Maya civilization occupied the south of Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador.

-

Portrait of K'inich Janaab Pakal I; 615–683; stucco; height: 43 cm (1 ft 5 in.); National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City)

-

Jade plaque of a Maya king; 400-800 (Classic period); height: 14 cm, width: 14 cm; found at Teotihuacan; British Museum (London).

-

Relief showing Aj Chak Maax presenting captives before ruler Itzamnaaj B'alam III of Yaxchilan; 22 August 783

Toltec

-

The Atlantes — columns in the form of Toltec warriors inTula.

-

An expressive orange-ware clay vessel in the Toltec style.

-

Toltec bird carving in granite at Tula

-

Toltec turtle vessel

Mixtec

-

Mixtec king and warlord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw (right) meeting with Toltec ruler Lord Four Jaguar, in a depiction from the pre-Columbian Codex Zouche-Nuttall.

-

Mixtec pectoral of gold and turquoise, Shield of Yanhuitlán. National Museum of Anthropology

-

Closeup view of Mixtec stone mosaic-work at Mitla. This was an inspiration for similar mosaics by Frank Lloyd Wright.

-

Mixtec incense burner

Totonac

-

Figure of a seated commander; 300–600; Art Institute of Chicago (USA)

-

Standing male figure; 600–900; earthenware; from central Veracruz (Mexico); Gardiner Museum (Toronto, Canada)

-

Sculpture; 700–900; andesite; height: 35.56 cm (14 in.)

-

Heads; circa 900; Leipzig Museum of Ethnography (Leipzig, Germany)

Huastec

Aztec

-

Double-headed serpent; 1450–1521; Spanish cedar wood (Cedrela odorata), turquoise, shell, traces of gilding and pine resin and Bursera resin for adhesive; 20.3 in. H; British Museum (London).

-

The original page 13 of theBibliothèque de l'Assemblée Nationale (Paris). This 13th trecena (of the Aztec sacred calendar) was under the auspices of the goddess Tlazōlteōtl, who is shown on the upper left wearing a flayed skin, giving birth to Centeōtl. The 13-day-signs of this trecena, starting with 1 Earthquake, 2 Flint/Knife, 3 Rain, etc., are shown on the bottom row and the right column

-

Aztec calendar stone; 1502–1521; basalt; diameter: 358 cm (141 in.); thick: 98 cm (39 in.); discovered on 17 December 1790 during repairs on the Mexico City Cathedral; National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City). The exact purpose and meaning of the Calendar Stone are unclear. Archaeologists and historians have proposed numerous theories, and it is likely that there are several aspects to its interpretation[40]

-

Museo del Templo Mayor (Mexico City). Templo Mayor, dedicated to Tlāloc. This jar, covered with stuccoand painted blue, is adorned with the visage of Tlāloc, identified by his coloration, ringed teeth and jaguar teeth

Central America and "Intermediate area"

Greater Chiriqui

Greater Nicoya The ancient peoples of the Nicoya Peninsula in present-day Costa Rica traditionally sculpted birds in jade, which were used for funeral ornaments.[41] Around 500 CE gold ornaments replaced jade, possibly because of the depletion of jade resources.[42]

Caribbean

-

Duho (Ceremonial wooden stool),Taíno, 1000-1500 CE, carved lignum vitae

-

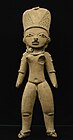

Taíno zemi, ironwood with shell inlay, Dominican Republic, 15th-16th-century bowl used for cohoba rituals[43]

-

-

Taíno batey ball court petroglyph, Caguana, Utuado, Puerto Rico

South American

The native civilizations were most developed in the

Hunter-gatherer tribes throughout the Amazon rainforest of Brazil also have developed artistic traditions involving tattooing and body painting. Because of their remoteness, these tribes and their art have not been studied as thoroughly as Andean cultures, and many even remain uncontacted.

Isthmo-Colombian Area

The Isthmo-Colombian Area includes some Central American countries (like Costa Rica and Panama) and some South American countries near them (like Colombia).

San Agustín

-

Zoomorphico-anthropomorphic figures from San Agustín Archaeological Park

-

Figure from San Agustín Archaeological Park

-

Double-spouted jar with strap handle; 500 BCE-500 CE; slip-painted ceramic; height: 21.27 cm (83⁄8 in.), width: 19.05 cm (71⁄2 in.), depth: 17.46 cm (67⁄8 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

-

Pendant; 1 CE-900; gold; 3.1 x 9.7 x 8.8 cm; Gold Museum (Bogotá, Colombia)

Calima

-

Funerary mask; 5th-1st century BCE; embossed gold; Ilama stage; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Animal-headed figure pendant; 1st–7th century; gold; height: 6.35 cm (21⁄2 in.); Yotoco stage; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Double spout and strap handle vessel with a mythological figure; 400–1200; slip-painted ceramic; height: 19.37 cm (75⁄8 in.), width: 19.05 cm (71⁄2 in.), depth: 10.32 cm (41⁄16in.); Yotoco stage; Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Tolima

-

Pendant; 1st-7th century; gold; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

-

Anthropomorphic pendant; 5th-10th century; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pendants in the form of flying fish; 10th-15th century; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Gran Coclé

-

Pedestal dish; 600–800; height: 15.24 cm (6 in.), diameter: 27.69 cm (107⁄8 in.); Walters Art Museum

-

Ceramic plate;University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology(USA)

-

Gold plaque from Sitio Conte; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Diquis

-

One of the stone spheres of Costa Rica

-

Ceremonial metate; 1500 BCE-1400; height: 56 cm (221⁄16 in.), width: 94.4 cm (373⁄16 in.), depth: 78 cm (3011⁄16 in.); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA)

-

Stone figure resembling a masked shaman; 1000–1500;Musée du quai Branly(Paris)

-

Two lobster-shaped pendants; 700–1550;Museo del Jade Marco Fidel Tristán Castro (San José, Costa Rica)

Nariño

-

Nose ornament; 7th-12th century; cantilever gold alloy; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Nose ornament; 7th-12th century; cantilever gold alloy; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Footed bowl depicting a pair of monkeys; 750–1250; resist-painted ceramic; height: 8.9 cm (31⁄2 in.), diameter of the bowl: 20.48 cm (81⁄16 in.), diameter of the foot: 7.94 cm (31⁄8 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

-

Gourd-shaped vessel; 850–1500; resist-painted ceramic; height: 26.35 cm (103⁄8in.), diameter: 20.32 cm (8 in.); Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Quimbaya

-

Lime container; 5th-9th century; gold; 23 cm (9 in) high; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City). Likely used by a member of theQuimbayaelite

-

Two statues caciques sitting on stools;Museum of the Americas (Madrid, Spain)

-

Quimbaya airplanes in Museum of the Americas (Madrid)

-

Ceramic figurine with tumbaga decoration; 1200–1500; Museum of the Americas

Muisca

-

Guatavita Lake region; Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

-

Mask; gold; 8.7 x 12.7 cm; Gold Museum (Bogotá)

-

Ceramic mask;Colombian National Museum(Bogotá)

Zenú

-

Two-headed deer-shaped ornament; circa 400–1000; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

-

Owl-shaped ornament; circa 400–1000; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Bird finial; 5th–10th century; gold; height 12.1 cm (43⁄4 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Olla with annular base and modeled figures; 500–1550; ceramic yellow-ware; height: 28.6 cm (11.2 in); width: 31.8 cm (12.5 in); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA)

Tairona

-

Small footed bowl with tiger head handles; 1000–1500; earthenware; 5 × 10.1 cm (2 × 4 in.); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA)

-

Ancestral figure; 1000–1550; brown stone; height: 18.1 cm (7.1 in), width: 4.8 cm (1.8 in); Walters Art Museum

-

Anthropomorphic pendant; 1000–1550; gold alloy casting; width: 14.6 cm (53⁄4 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Anthropomorphic pendant; 18th century; gold; height: 13 cm (5.1 in), width: 13 cm (5.1 in), depth: 4.5 cm (1.7 in);Musée du Quai Branly(Paris)

Andes Region

Valdivia

-

Parrot figure; 4000-1500 BC

-

Ancestor statue with six faces; Casa del Alabado Museum of Pre-Columbian Art (Quito, Ecuador)

-

Female figurine; 2600-1500 BCE; ceramic; 11 x 2.9 x 1.6 cm (45⁄16 x 11⁄8 x 5⁄8 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Jaguar-shaped figure; 2000-1000 BCE; green serpentine

Chavín

-

A Chavin stone sculpture in the shape of a head of a man, an ornament from a wall; 9th century BCE; Museo de la Nación (Lima, Peru)

-

Chavin crown; 1200 BCE-1 CE (Formative Epoch); gold; Larco Museum(Lima)

-

Stirrup-spout vessel with scroll ornament; ceramic; 900-200 BCE; height: 18.4 cm, diameter: 16.2 cm; Dallas Museum of Art (Dallas, Texas, USA)

-

Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú (Lima, Peru).

Paracas

-

Paracas mantle 200 CE Larco Museum, Lima-Perú

-

Paracas Necropolis, 0-100 . This is a "double fish" (probably sharks) design. Brooklyn Museumcollections

Nasca

-

A fish-like double spout and bridge vessel from Cahuachi

-

An example of theNasca Lines

Moche

-

Ceremonial headdress; 300–600; gold, chrysocolla & shells

-

2 ear ornaments with winged runners; 5th century-8th century; gold, turquoise, sodalite & shell; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Recuay

-

Seated figure; 2nd century BCE-3rd century CE; stone; 63.5 × 44.45 × 20.32 cm (25 × 171⁄2 × 8 in.); weight: 102.5129 kg (226 lb.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Effigy bottle; 200 BCE 500 CE; earthenware & slip paint; height: 28.2 cm (11.1 in.), diameter: 20.5 cm (8 in.); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA)

-

Vase with music scene; 300 BCE-300 CE painted clay; height: 21.5 cm; from northern coastal region of Peru; Kloster Allerheiligen (Schaffhausen; Switzerland)

-

Textile fragment; 4th–6th century; camelid hair; overall: 33.02 x 82.55 cm (13 × 321⁄2 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Tolita

-

Standing figure; 1st century BCE-1st century CE; emossed gold; height: 22.9 cm (9 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Nose-ornament; 1st-5th century; gold and embossed silver; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wari

-

Ornament in the shape of a bird; 6th-10th century; embossed gold; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Anthropomorphic figure; 7th-10th century; burned clay; from Mantaro Valley;Museum Rietberg (Zürich, Switzerland)

-

Mozaic figure; 7th–11th century; wood with shell-and-stone inlay & silver; 10.2 x 6.4 x 2.6 cm; from theFort Worth, Texas, USA)

-

Sacrificer-shaped container; circa 769–887; wood & cinnabar; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA)

Lambayeque/Sican

-

Beaker cups; 9th-11th century; gold; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Cup; 900–1100; Art Institute of Chicago (USA)

-

Sican headdress mask; 10th-11th century; gold, silver & paint; height: 29.2 cm (111⁄2 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Ceremonial knife (tumi); 10th-13th century; gold, turquoise, greenstone & shell; height: 33 cm (1 ft. 1 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

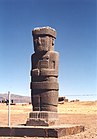

Tiwanaku

-

Closeup of carved stone tenon-head embedded in wall of Tiwanaku's Semi-subterranean Temple

-

Anthropomorphic receptacle

-

Ponce stela in the sunken courtyard of the Tiwanaku's Kalasasaya temple

Capulí

-

Pendant; 4th–10th century; gold; height: 14.6 cm (53⁄4 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Face-shaped plaque; 7th–12th century; gold; diameter: 1.9 cm (35⁄8 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Male figure-shaped coca chewer on bench; 9th–15th century; ceramic; height: 21.6 cm (81⁄2 in.), width: 10.2 cm (4 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Bowl supported by 3 figures; 850–1500; resist-painted ceramic; height: 28.58 cm (111⁄4 in.), diameter of the bowl: 19.69 cm (73⁄4 in.); from Colombia; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

Chimú empire

-

Chimú gold apparel, 1300 CE, Larco Museum, Lima, Perú

-

Ceramic llama vessel, 1100–1400 CE, Museo de América, Madrid, Spain

-

Chimu mantle, Late Intermediate Period, 1000–1476 CE, featuring pelicans and tuna

Chancay

-

Beaded wrist ornament, ca. 1100–1399 CE, hand-ground shell beads, cordage, 4.25 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Fragment ofslit tapestry with eccentric weave and applied fringe, 1000–1470, camelid fiber and cotton, 163⁄4 x 18 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art

-

Vessel; 1000–1470; earthenware, slip paint; height: 29.6 cm (11.6 in.); diameter: 12.1 cm (4.7 in.); Walters Art Museum

Inca

-

Hammered andRepoussedgold mural

-

Inca tunic

-

Silver and gold Inca statuettes, from the Musee D'Auch

Amazonia

Traditionally limited in access to stone and metals, Amazonian

The Island of Marajó, at the mouth of the Amazon River was a major center of ceramic traditions as early as 1000 CE[44] and continues to produce ceramics today, characterized by cream-colored bases painted with linear, geometric designs of red, black, and white slips.

With access to a wide range of native bird species, Amazonian

-

Cave painting, Serra da Capivara National Park

-

Ceramic zoomorphic vase,Belém, Brazil

-

Enawene-nawefeatherwork and body art

Modern and contemporary

Beginnings of contemporary Native American art

Pinpointing the exact time of emergence of "modern" and contemporary Native art is problematic. In the past, Western art historians have considered use of Western art media or exhibiting in international art arena as criteria for "modern" Native American art history.

The notion that fine art cannot be functional has not gained widespread acceptance in the Native American art world, as evidenced by the high esteem and value placed upon rugs, blankets, basketry, weapons, and other utilitarian items in Native American art shows. A dichotomy between fine art and craft is not commonly found in contemporary Native art. For example, the Cherokee Nation honors its greatest artists as Living Treasures, including frog- and fish-gig makers, flint knappers, and basket weavers, alongside sculptors, painters, and textile artists.[49] Art historian Dawn Ades writes, "Far from being inferior, or purely decorative, crafts like textiles or ceramics, have always had the possibility of being the bearers of vital knowledge, beliefs and myths."[50]

Recognizable art markets between Natives and non-Natives emerged upon contact, but the 1820–1840s were a highly prolific time. In the Pacific Northwest and the Great Lakes region, tribes dependent upon the rapidly diminishing fur trade adopted art production a means of financial support. A painting movement known as the Iroquois Realist School emerged among the Haudenosaunee in New York in the 1820s, spearheaded by the brothers David and Dennis Cusick.[51]

African-Ojibwe sculptor,

Ho-Chunk artist, Angel De Cora was the best known Native American artist before World War I.[53] She was taken from her reservation and family to the Hampton Institute, where she began her lengthy formal art training.[54] Active in the Arts and Crafts movement, De Cora exhibited her paintings and design widely and illustrated books by Native authors. She strove to be tribally specific in her work and was revolutionary for portraying Indians in contemporary clothing of the early 20th century. She taught art to young Native students at Carlisle Indian Industrial School and was an outspoken advocate of art as a means for Native Americans to maintain cultural pride, while finding a place in mainstream society.[55]

The Kiowa Six, a group of Kiowa painters from Oklahoma, met with international success when their mentor, Oscar Jacobson, showed their paintings in First International Art Exposition in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1928.[56] They also participated in the 1932 Venice Biennale, where their art display, according to Dorothy Dunn, "was acclaimed the most popular exhibit among all the rich and varied displays assembled."[57]

The

Basketry

A range of native grasses provides material for Arctic baskets, as does baleen, which is a 20th-century development. Baleen baskets are typically embellished with walrus ivory carvings.[58] Cedar bark is often used in northwest coastal baskets. Throughout the Great Lakes and northeast, black ash and sweetgrass are woven into fancy work, featuring "porcupine" points, or decorated as strawberries. Bark baskets are traditional for gathering berries. Rivercane is the preferred material in the Southeast, and Chitimachas are regarded as the finest rivercane weavers. In Oklahoma, rivercane is prized but rare so baskets are typically made of honeysuckle or buckbrush runners. Coiled baskets are popular in the southwest and the Hopi and Apache in particular are known for pictorial coiled basketry plaques. The Tohono O'odham are well known for their basket-weaving prowess, and evidenced by the success of Annie Antone and Terrol Dew Johnson.

California and Great Basin tribes are considered some of the finest basket weavers in the world. Juncus is a common material in southern California, while sedge, willow, redbud, and devil's claw are also used. Pomo basket weavers are known to weave 60–100 stitches per inch and their rounded, coiled baskets adorned with quail's topknots, feathers, abalone, and clamshell discs are known as "treasure baskets". Three of the most celebrated Californian basket weavers were Elsie Allen (Pomo), Laura Somersal (Wappo), and the late Pomo-Patwin medicine woman, Mabel McKay,[60] known for her biography, Weaving the Dream. Louisa Keyser was a highly influential Washoe basket weaver.

A complex technique called "doubleweave," which involves continuously weaving both an inside and outside surface is shared by the

Today basket weaving often leads to environmental activism. Indiscriminate pesticide spraying endangers basket weavers' health. The

Beadwork

Beadwork is a quintessentially Native American art form, but ironically uses beads imported from Europe and Asia. Glass beads have been in use for almost five centuries in the Americas. Today a wide range of beading styles flourish.

In the Great Lakes, Ursuline nuns introduced floral patterns to tribes, who quickly applied them to beadwork.

Most Native beadwork is created for tribal use but beadworkers also create conceptual work for the art world.

Marcus Amerman, Choctaw, one of today's most celebrated bead artists, pioneered a movement of highly realistic beaded portraits.[72] His imagery ranges from 19th century Native leaders to pop icons such as Janet Jackson and Brooke Shields.

Roger Amerman, Marcus' brother, and Martha Berry, Cherokee, have effectively revived Southeastern beadwork, a style that had been lost because of forced removal from tribes to Indian Territory. Their beadwork commonly features white bead outlines, an echo of the shell beads or pearls Southeastern tribes used before contact.[73]

Jamie Okuma (

The widespread popularity of glass beads does not mean aboriginal bead making is dead. Perhaps the most famous Native bead is

Ceramics

Ceramics have been created in the Americas for the last 8000 years, as evidenced by pottery found in Caverna da Pedra Pintada in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon.[77] The Island of Marajó in Brazil remains a major center of ceramic art today.[78] In Mexico, Mata Ortiz pottery continues the ancient Casas Grandes tradition of polychrome pottery. Juan Quezada is one of the leading potters from Mata Ortiz.[79]

In the Southeast, the

Pueblo people are particularly known for their ceramic traditions.

While northern potters are not as well known as their southern counterparts, ceramic arts extend as far north as the Arctic. Inuit potter,

Today contemporary Native potters create a wide range of ceramics from functional pottery to monumental ceramic sculpture.

Jewelry

-

Sac & Fox), Oklahoma, 1984, Oklahoma Historical Society

-

Silver overlayNavajo), New Mexico, c. 1980s

-

Woolaroc

-

Eastern Band Cherokee)

Performance art

Performance art is a new art form, emerging in the 1960s, and so does not carry the cultural baggage of many other art genres. Performance art can draw upon storytelling traditions, as well as music and dance, and often includes elements of installation, video, film, and textile design.

Performance allows artists to confront their audience directly, challenge long held stereotypes, and bring up current issues, often in an emotionally charged manner. "[P]eople just howl in their seats, and there's ranting and booing or hissing, carrying on in the audience," says Rebecca Belmore of the response to her work.[85] She has created performances to call attention to violence against and many unsolved murders of First Nations women. Both Belmore and Luna create elaborate, often outlandish outfits and props for their performances and move through a range of characters. For instance, a repeating character of Luna's is Uncle Jimmy,[86] a disabled veteran who criticizes greed and apathy on his reservation.

On the other hand, Marcus Amerman, a Choctaw performance artist, maintains a consistent role of the Buffalo Man, whose irony and social commentary arise from the odd situations in which he finds himself, for instance a James Bond movie or lost in a desert labyrinth.[87] Jeff Marley, Cherokee, pulls from the tradition of the "booger dance" to create subversive, yet humorous, interventions that take history and place into account.[88]

A Bolivian

Performance art has allowed Native Americans access to the international art world, and Rebecca Belmore mentions that her audiences are non-Native;[85] however, Native American audiences also respond to this genre. Bringing It All Back Home, a 1997 film collaboration between James Luna and Chris Eyre, documents Luna's first performance at his own home, the La Jolla Indian Reservation. Luna describes the experience as "probably the scariest moment of my life as an artist ... performing for the members of my reservation in the tribal hall."[90]

Photography

Today innumerable Native people are professional art photographers; however, acceptance to the genre has met with challenges.

Printmaking

Although it is widely speculated that the ancient

Printmaking has flourished among

Many Native painters transformed their paintings into fine art prints.

In Chile,

Sculpture

Native Americans have created sculpture, both monumental and small, for millennia. Stone sculptures are ubiquitous through the Americas, in the forms of

– sacred, three-pointed stone sculptures.Inuit artists sculpt with walrus ivory, caribou antlers, bones, soapstone, serpentinite, and argillite. They often represent local fauna and humans engaged in hunting or ceremonial activities.

The Northwest Coastal tribes are known for their woodcarving – most famously their monumental

In the Southeast, woodcarving dominates sculpture.

-

For Life in all Directions,Santa Clara Pueblo), bronze, NMAI

-

Amambay Department, Paraguay, 2008

-

Each/Other by Marie Watt and Cannupa Hanska Luger, 2021

Textiles

Fiberwork dating back 10,000 years has been unearthed from Guitarrero Cave in Peru.[101] Cotton and wool from alpaca, llamas, and vicuñas have been woven into elaborate textiles for thousands of years in the Andes and are still important parts of Quechua and Aymara culture today. Coroma in Antonio Quijarro Province, Bolivia is a major center for ceremonial textile production.[102] An Aymara elder from Coroma said, "In our sacred weavings are expressions of our philosophy, and the basis for our social organization... The sacred weavings are also important in differentiating one community, or ethnic group, from a neighboring group..."[103]

Mayan women have woven cotton with backstrap looms for centuries, creating items such as huipils or traditional blouses. Elaborate Maya textiles featured representations of animals, plants, and figures from oral history.[105] Organizing into weaving collectives have helped Mayan women earn better money for their work and greatly expand the reach of Mayan textiles in the world.

Seminole seamstresses, upon gaining access to sewing machines in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, invented an elaborate appliqué patchwork tradition. Seminole patchwork, for which the tribe is known today, came into full flower in the 1920s.[106]

Great Lakes and Prairie tribes are known for their

Pueblo men weave with cotton on upright looms. Their mantas and sashes are typically made for ceremonial use for the community, not for outside collectors.

In 1973, the Navajo Studies Department of the Diné College in Many Farms, Arizona, wanted to determine how long it took a Navajo weaver to create a rug or blanket from sheep shearing to market. The study determined the total amount of time was 345 hours. Out of these 345 hours, the expert Navajo weaver needed: 45 hours to shear the sheep and process the wool; 24 hours to spin the wool; 60 hours to prepare the dye and to dye the wool; 215 hours to weave the piece; and only one hour to sell the item in their shop.[107]

Customary textiles of Northwest Coast peoples using non-Western materials and techniques are enjoying a dramatic revival.

Experimental 21st-century textile artists include

Cultural sensitivity and repatriation

As in most cultures, Native peoples create some works that are to be used only in sacred, private ceremonies. Many sacred objects or items that contain medicine are to be seen or touched by certain individuals with specialized knowledge. Many

Two

Tribes and individuals within tribes do not always agree about what is or is not appropriate to display to the public. Many institutions do not exhibit

Museum representation

Indigenous American arts have had a long and complicated relationship with museum representation since the early 1900s. In 1931, The Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts was the first large scale show that held Indigenous art on display. Their portrayal in museums grew more common later in the 1900s as a reaction to the Civil Rights Movement. With the rising trend of representation in the political atmosphere, minority voices gained more representation in museums as well.[119]

Although Indigenous art was being displayed, the curatorial choices on how to display their work were not always made with the best of intentions. For instance, Native American art pieces and artifacts would often be shown alongside dinosaur bones, implying that they are a people of the past and non-existent or irrelevant in today's world.[120] Native American remains were on display in museums up until the 1960s.[121]

Though many did not yet view Native American art as a part of the mainstream as of the year 1992, there has since then been a great increase in volume and quality of both Native art and artists, as well as exhibitions and venues, and individual curators. Such leaders as the director of the National Museum of the American Indian insist that Native American representation be done from a first-hand perspective.[122] The establishment of such museums as the Heard Museum and the National Museum of the American Indian, both of which trained spotlights specifically upon Native American arts, enabled a great number of Native artists to display and develop their work.[123] For five months starting in October 2017, three Native American works of art selected from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection to be exhibited in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[124]

Museum representation for Indigenous artists calls for great responsibility from curators and museum institutions. The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 prohibits non-Indigenous artists from exhibiting as Native American artists. Institutions and curators work discussing whom to represent, why are they being chosen, what Indigenous art looks like, and what its purpose is. Museums, as educational institutions, give light to cultures and narratives that would otherwise go unseen; they provide a necessary spotlight and who they choose to represent is pivotal to the history of the represented artists and culture.

See also

- Archaeology of the Americas

- Indian Arts and Crafts Board

- Indian Space Painters

- List of indigenous artists of the Americas

- List of Native American artists

- Native American fashion

- Native American jewelry

- Native American pottery

- Painting in the Americas before Colonization

- Paraguayan indigenous art

- Pre-Columbian art

- Prehistoric art

- Timeline of Native American art history

Citations

- ^ "Ice Age Art from Florida". Past Horizons. 23 June 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Rawls, Sandra (4 June 2009). "University of Florida: Epic carving on fossil bone found in Vero Beach". Vero Beach 32963. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer. "Earliest Mammoth Art: Mammoth on Mammoth". Discovery News. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Associated Press (22 June 2011). "Ancient mammoth or mastodon image found on bone in Vero Beach". Gainesville Sun. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.05.022.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISBN 978-0-8061-3053-8.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble. Scientist at Work: Anna C. Roosevelt; Sharp and To the Point In Amazonia. New York Times. 23 April 1996

- .

- ^ Stone-Miller, 17

- ^ Hessel, 20

- ^ Hessel, 21

- ^ A History of Native Art in Canada and North America. Native Art in Canada. 11.June.2010

- ^ a b Shenadoah, Chief Leon. Haudenosaunee Confederacy Policy On False Face Masks. Archived 12 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine Peace 4 Turtle Island. 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- ^ a b Crawford and Kelley, pp. 496–497.

- ^ Newark Museum – Collection

- ^ "NMAI Indian Humor – Graves". National Museum of the American Indian. Internet Archive: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Poverty Point-2000 to 1000 BCE". Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "CRT-Louisiana State Parks Fees, Facilities and Activities". Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ Mississippian Period: Overview

- ISBN 978-0-8130-1462-3.

- ISBN 978-1-56164-032-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8130-2645-9.

- ^ Material Archived 6 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine from the State Archives of Florida.

- ^ Pyburn, Anne. "Peoples of the Great Plains". Indiana University.. Retrieved 29 January 2010

- ^ "Native American and First Nations' GIS." Native Geography. Dec 2000. Retrieved 29 January 2010

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, 131

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, 132

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, 136

- ^ Garey-Sage, Darla. "Contemporary Great Basin Basketmakers." The Online Nevada Encyclopedia.. Retrieved 17 May 2010

- ^ ISSN 0361-7181.

- ^ ISSN 1947-461X.

- ^ Cameron, Constance (2000). "Animal Effigies from Coastal Southern California" (PDF). Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly. 36 (2): 30–52.

- ^ "Ancestral Hopi Pottery". Archived 8 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Arizona State Museum. 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2010

- ^ "Chaco Canyon." Archived 4 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Minnesota State Museum, Mankato. Retrieved 14 August 2010

- ^ "Paracas | Paracas Textiles, Mummies & Geoglyphs | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "The British Museum Website". Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Covarrubias, p. 193.

- ^ Mason 1929, p. 182, from Richardson 1932, pp. 48–49.

- ^ "The British Museum Website". Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ K. Mills, W. B. Taylor & S. L. Graham (eds), Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History, 'The Aztec Stone of the Five Eras', p. 23

- ^ Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. "Jade in Costa Rica". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.(October 2001)

- ^ "Curly-Tailed Animal Pendant [Panama; Initial style] (91.1.1166)" In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2006)

- ^ "Deity Figure (Zemi) Dominican Republic; Taino (1979.206.380)"

- ^ a b Wilford, John Noble. Scientist at Work: Anna C. Roosevelt;Sharp and To the Point In Amazonia. New York Times. 23 April 1996. Retrieved 26 September 2009

- ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5.

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, 209.

- ^ Dunn, p. xxviii.

- ^ Levenson, pp. 554–555.

- ^ Chavez, Will. 2006 Cherokee National Living Treasure artists announced. Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Cherokee Phoenix. 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2009

- ^ Ades, 5

- ^ Sturtevant, p. 129

- ^ Wolfe, pp. 12, 14, 108, and 120

- ^ Hutchinson, p. 740

- ^ Hutchinson, p. 742

- ^ Hutchinson, p. 754

- ^ Pochoir prints of ledger drawings by the Kiowa Five, 1929. Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Retrieved 1 March 2009

- ^ Dunn, 240

- ^ a b Hessel, Arctic Spirit, p. 17

- ^ Lisa Telford. Archived 13 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Artist Trust. Retrieved 16 March 2009

- ^ Dalrymple, p. 2

- ^ Indian Cultures from Around the World: Yanomamo Indians. Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Hands Around the World. Retrieved 16 March 2009

- ^ Indian Cultures from Around the World: Waura Indians. Archived 10 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Hands Around the World.. Retrieved 16 March 2009

- ^ Church, Kelly. Black Ash. Archived 21 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Art of Kelly Church and Cherish Parrish. 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2009

- ^ Dowell, JoKay. Cherokees discuss native plant society. Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved 16 March 2009

- ^ Terrol Dew Johnson and Tristan Reader, Tohono O'odham Community Action Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Leadership for a Changing World. 25 April 2003. Retrieved 16 March 2009

- ^ Dubin, p. 50

- ^ Dubin, p. 218

- ^ Berlo and Philips, p. 151

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, p. 146

- ^ Hillman, Paul. The Huichol Web of Life: Creation and Prayer. Archived 18 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Bead Museum.. Retrieved 13 March 2009

- ^ Lopez, Antonio. Focus Artists: Teri Greeves.[permanent dead link] Southwest Art. 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, p. 32

- ^ Berlo and Phillips, p. 87

- ^ Indyke, Dottie (May 2001). "Native Arts: Jamie Okuma". Southwest Art Magazine.

- ^ Dubin, p. 170-171

- ^ Original Wampum Art. Elizabeth James Perry. 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2009

- ^ Mann, 297

- ^ Vision of Brazil. Archived 31 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mata Otriz Pottery. Fine Mexican Ceramics. 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009

- ^ Hill, 158

- ^ Helen Cordero. Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Arts of the Southwest.. Retrieved 17 May 2009

- ^ Inuit Pottery from Alma Houston's Private Collection. Archived 23 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Houston North Gallery.. Retrieved 17 May 2009

- ^ Nora Naranjo-Morse. Women Artists of the American West.. Retrieved 17 May 2009

- ^ Nottage, p. 25

- ^ a b Ryan, 146

- ^ Nottage, p. 31

- ^ Performance. Marcus Amerman.. Retrieved 5 March 2009

- ^ Out of bounds. Jeff Marley.. Retrieved 3 June 2014

- ^ Lord, Erica. Erica Lord. 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2009

- ^ Nottage, p. 30

- ^ Artwork in Our People, Our Land, Our Images. Archived 29 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.. Retrieved 1 March 2009

- ^ "Mique'l Askren, Bringing our History into Focus: Re-Developing the Work of B.A. Haldane, 19th-century Tsimshian Photographer, Blackflash: Seeing Red, Volume 24, No. 3, 2007, pp. 41–47". Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Masayesva and Younger, p. 42.

- ^ a b Hessel, Arctic Spirit, p. 49

- ^ Hessel, Arctic Spirit, p. 52

- ^ a b Hessel, Arctic Spirit, p. 50

- ^ Jose Santos Chavez. The Ohio Channel Media Center.. Retrieved 5 March 2009

- ^ Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts.. Retrieved 5 March 2009

- ^ Tall Chief, Russ. Splendor in the Glass: Masters of a New Media. Native Peoples Magazine. 27 July 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2009

- ^ Amanda Crowe. Cherokee Heritage Trails. 2003. Retrieved 11 April 2009

- ^ Stone-Miller, Rebecca. Art of the Andes, p. 17

- ^ Siegal, p. 15

- ^ Siegal, p. 15-16

- ^ About Molas. Indigenous Art from Panamá.. Retrieved 28 March 2009

- ^ Geise, Paula. Clothing, Regalia, Textiles from the Chiapas Highlands of Mexico. Mything Links. 22 December 1999. Retrieved 28 March 2009

- ^ Blackard, David M. and Patsy West. Seminole Clothing: Colorful Patchwork. Archived 16 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine Seminole Tribe of Florida.. Retrieved 11 April 2009

- ^ "Native American Art- Navajo Blanket Weaving".

- ^ Perry, Rachel. Martha (Marty) Gradolf: Idea Weaver. Our Brown County. Retrieved 28 March 2009

- ^ Indyke, Dottie. Ramona Sakiestewa. Southwest Art. Retrieved 28 March 2009

- ^ "Katsinam from the IARC Collection." School for Advanced Research.. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- ^ "Birch Bark Scrolls." University of Pennsylvania, School of Arts and Sciences.. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- ^ Potter, Dottie. "The Selling of Indian Culture." Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dakota-Lakota-Nakota Human Rights Advocacy Coalition. 21–28 June 2002. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- ^ "Sand Painting." Crystal Links: Navajo Nation.. Retrieved 16 May 2011

- ^ Phillips 49

- ^ Rosenbaum, Lee. "Shows That Defy Stereotypes", Wall Street Journal. 15 March 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions." National Park Service, Department of the Interior: NAGPRA.. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- ^ "Repatriation of Artifacts." The Canadian Encyclopedia.. René R. Gadacz. 03/03/2012.

- ^ Toensing, Gale Courey. "Yale Returning Remains, Artifacts to Peru." Indian Country Today. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011

- .

- ^ Abu Hadal, Katherine (20 February 2013). "Why Native American Art Doesn't Belong in the American Museum of Natural History". Indian Country Today. Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ King, Duane H. (2009). "Exhibiting Culture: American Indians and Museums". Tulsa Law Review. 45 (1): 25–32.

- ^ Brockman, Joshua. "A New Dawn for Museums of Native American Art". The New York Times, 20 August 2005, www.nytimes.com/2005/08/20/arts/design/a-new-dawn-for-museums-of-native-american-art.html.

- S2CID 191640737.

- ^ Yount, Sylvia. "Redefining American Art: Native American Art in The American Wing". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, I.e. The Met Museum, 21 February 2017, www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2017/native-american-art-the-american-wing.

References

General

- Crawford, Suzanne J. and Dennis F. Kelley, eds. American Indian Religious Traditions: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 978-1-57607-517-3.

- Levenson, Jay A., ed. (1991) Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05167-0.

- Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4006-X.

- Nottage, James H. Diversity and Dialogue: The Eiteljorg Fellowship for Native American Fine Art, 2007. Indianapolis: Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, 2008. ISBN 978-0-295-98781-1.

- Phillips, Ruth B. "A Proper Place for Art or the Proper Arts of Place? Native North American Objects and the Hierarchies of Art, Craft and Souvenir." Lynda Jessup with Shannon Bagg, eds. On Aboriginal Representation in the Gallery. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-660-18749-5.

North America

- ISBN 978-0-19-284218-3.

- Dalrymple, Larry (2000). California and Great Basin Indian Basketmakers: The Living Art and Fine Tradition. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-89013-337-9

- Dubin, Lois Sherr (1999). North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment: From Prehistory to the Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3689-5

- Dunn, Dorothy. American Indian Painting of the Southwest and Plains Areas. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1968. ASIN B000X7A1T0.

- Hessel, Ingo (2006). Arctic Spirit: Inuit Art from the Albrecht Collection at the Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ: Heard Museum. ISBN 978-1-55365-189-5.

- Hill, Sarah H. (1997). Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and Their Basketry. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4650-3.

- Hutchinson, Elizabeth (Dec 2001). "Modern Native American Art: Angel DeCora's Transcultural Aesthetics." Art Bulletin. Vol. 83, 4: 740–756.

- Masayesva, Victor and Erin Younger (1983). Hopi Photographers: Hopi Images. Sun Tracks, Tucson, Arizona. ISBN 978-0-8165-0804-4.

- Shearar, Cheryl (2000). Understanding Northwest Coast Art: A Guide to Crests, Beings and Symbols. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55054-782-5.

- Porter, Frank W. (1988). Native American Basketry: An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25363-3.

- Ryan, Allan J. (1999). The Trickster Shift: Humor and Irony in Contemporary Native Art. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0704-0.

- Sturtevant, William C. (2007). "Early Iroquois Realist Painting and Identity Marking." Three Centuries of Woodlands Indian Art. Vienna: ZKF Publishers: 129–143. ISBN 978-3-9811620-0-4.

- Wolfe, Rinna Evelyn (1998). Edmonia Lewis: Wildfire in Marble. Parsippany, NJ: Dillon Press. ISBN 0-382-39714-2.

Mesoamerica and Central America

- Mason, J. Alden(1929). "Zapotec Funerary Urns from Mexico". The Museum Journal. 20. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum: 176–201.

- Covarrubias, Miguel (1957). Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

South America

- Ades, Dawn (2006). Art in Latin America: The Modern Era 1820–1980. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04561-1.

- Siegal, William (1991). Aymara-Bolivianische Textilien. Krefeld: Deutsches Textilmuseum. ISBN 978-1-135-96629-4.

- Stone-Miller (2002). Art of the Andes: from Chavín to Inca. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20363-7.

Further reading

- Berlo, Janet C.; et al. (1998). Native paths: American Indian art from the collection of Charles and Valerie Diker. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870998560.

- Mark Jarzombek, Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective, (New York: Wiley & Sons, August 2013)

- Rushing III, W. Jackson (ed.) (1999). Native American Art in the Twentieth Century. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13747-0.

- Bernal, I; Coe, M; et al. (1973). The Iconography of Middle American sculpture. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (see index)

- Gardiner, Susannah (25 April 2022). "Who Gets to Define Native American Art?". Smithsonian Magazine.

External links

- National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico, islc.net

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- North American art, starting at 8000 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Central American art, starting at 8000 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- South American art, starting at 8000 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Online database of the Plains Indian Museum, on the website of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center

- Elizabeth Willis DeHuff Collection of American Indian Art from the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- American Indian Art, Oklahoma Historical Society

- Native Arts Collective, Profiles of many contemporary Native American artists

- Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520–1820.

- Native American Art Studies Association

![Kunz Axe; 1200-400 BCE; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)[36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/British_Museum_Mesoamerica_052.jpg/80px-British_Museum_Mesoamerica_052.jpg)

![Ceramic urn, 200 BCE – 800 CE, British Museum.[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/British_Museum_Zapotec_funerary_urn_1.jpg/100px-British_Museum_Zapotec_funerary_urn_1.jpg)

![Aztec calendar stone; 1502–1521; basalt; diameter: 358 cm (141 in.); thick: 98 cm (39 in.); discovered on 17 December 1790 during repairs on the Mexico City Cathedral; National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City). The exact purpose and meaning of the Calendar Stone are unclear. Archaeologists and historians have proposed numerous theories, and it is likely that there are several aspects to its interpretation[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne%2C_sog._Aztekenkalender%2C_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG/140px-1479_Stein_der_f%C3%BCnften_Sonne%2C_sog._Aztekenkalender%2C_Ollin_Tonatiuh_anagoria.JPG)

![Taíno zemi, ironwood with shell inlay, Dominican Republic, 15th-16th-century bowl used for cohoba rituals[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/Zemi_figure_Metropolitan.jpg/84px-Zemi_figure_Metropolitan.jpg)