Haryanvi people

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 26 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| India (Haryana, Delhi) | |

| Languages | |

| Hindi (Haryanvi), English, and Punjabi | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Minority: Sikhism, Islam, and Jainism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples |

The Haryanvi people are an

History

Haryana has been inhabited since the pre-historic period. Haryana was part of

In 1192, Chahamanas were defeated by Ghurids in Second Battle of Tarain.[10] In 1398, Timur attacked and sacked the cities of Sirsa, Fatehabad, Sunam, Kaithal and Panipat.[12][13] In the

In 1966, the Punjab Reorganisation Act (1966) came into effect, resulting in the creation of the state of Haryana on 1 November 1966.[15]

Distribution

Haryanvis within Haryana

The main communities in Haryana are Yadav,

Haryanvi diaspora overseas

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) |

There is increasingly large diaspora of Haryanvis in

, etc.In Australia, the community lives mainly in Sydney and Melbourne, has set up Association of Haryanvis in Australia (AHA) which organise events.[17]

In Singapore, the community has set up the Singapore Haryanvi Kunba organisation in 2012 which also has a Facebook group of same name. Singapore has Arya Samaj and several Hindu temples.

Culture

Language

Haryanvi, like

Folk music and dance

Folk music is integral part of Haryanvi culture. Folk song are sung during occasion of child birth, wedding, festival, and Satsang (singing religious songs).

Cuisine

Haryana is agricultural state known for producing foodgrains such as wheat, barley, pearl millet, maize, rice and high-quality dairy. Daily village meal in Haryana consist of a simple thali of roti, paired with a leafy stir-fry (saag in dishes such as gajar methi or aloo palak), condiments such as chaas, chutney, pickles. Some known Haryanvi dishes are green choliya (green chickpeas), bathua yogurt, bajre ki roti, sangri ki sabzi (beans), kachri ki chutney (wild cucumber) and bajre ki khichdi. Some sweets are panjiri and pinni prepared by unrefined sugar like bura and shakkar and diary. Malpua are popular during festivals.[19]

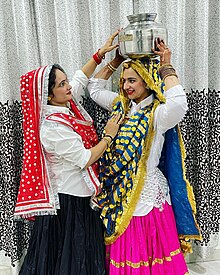

Clothes

Traditional attire for men is turban, shirt, dhoti, jutti and cotton or woollen shawl. Traditional attire for female is typically an orhna (veil), shirt or angia (short blouse), ghagri (heavy long skirt) and Jitti. Saris are also worn. Traditionally the Khaddar (coarse cotton weave cloth) is a frequently used as the fabric.[20][21]

Cinema

The First movie of Haryanvi cinema is Dharti which was released in 1968. The first financially successful Haryanvi movie was

Notable people

- Anangpal Tomar, king

- Arvind Kejriwal, politician

- Babita Kumari, wrestler

- Baje Bhagat, poet and writer

- Bajrang Punia, Wrestler

- Bansi Lal, politician

- Dayachand Mayna, poet and freedom fighter

- Dhruv Rathee, YouTuber

- Dushyant Chautala, politician

- Geeta Phogat, wrestler

- Hemu, emperor

- Jat Mehar Singh Dahiya, poet and freedom fighter

- Juhi Chawla, actress

- Lakhmi chand, poet, folk singer

- Mahavir Singh Phogat, wrestler

- Mallika Sherawat, actress

- Manushi Chhillar, Miss World 2017

- Ashok Chakrarecipient

- Neeraj Chopra, Javelin thrower

- Priyanka Phogat, wrestler

- Rajkummar Rao, actor

- Baba Ramdev, yoga guru

- Randeep Hooda, actor

- Ravi Kumar Dahiya, wrestler

- Ravi Kumar Punia, Football Player

- Rao Gopal Dev, king

- Rao tularam, freedom fighter

- Ritu Phogat, wrestler

- Sakshi Malik, wrestler

- Saina Nehwal, badminton player

- Satish Kaushik, actor, director, writer

- Santosh yadav

- Subhash Chandra, media entrepreneur and politician

- Sunil Grover, actor and comedian

- Sushil Kumar, wrestler

- Vijender Singh, boxer

- Vikas Krishan Yadav, boxer

- Vinesh Phogat, wrestler

- Virender Sehwag, cricket player

- Yogeshwar Dutt, wrestler

- Yuzi chahal, cricket player

References

- ^ "The way tough Haryanvis speak". tribuneindia. 28 December 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Social Status of a Haryanvi Rural Woman: A Reflective Study through Folk Songs". iitd.ac.com. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "No takers in their own land".

- ^ "Establishing the continuity of our local languages within the region". Hindustan Times. 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2023 – via Press Reader.

- ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ Pletcher 2010, p. 63.

- ^ Witzel 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Witzel 1995.

- ^ Hans Bakker 2014, p. 79.

- ^ a b Upinder Singh 2008, p. 571.

- ^ Sarkar 1960, p. 66.

- ^ Elliot, Sir Henry Miers; Dowson, John (1871). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period: Ed. from the Posthumous Papers of the Late Sir H. M. Elliot . Trübner and Company. pp. 427–31.

- ^ Phadke, H.A. (1990). Haryana, Ancient and Medieval. Harman Publishing House. p. 123.

- ISBN 978-0-313-37462-3.

- ^ the punjab reorganisation act, 1966 - Chief Secretary, Haryana (PDF), retrieved 12 November 2015

- ISBN 9788170249856.

- ^ "Australian Haryanvi community celebrates Teej Mela in style". nriaffairs. 24 July 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-8131300466.

- ^ "Haryanvi thali: Not just 'dhaba' fare". livemint. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Arihant Experts, Haryana SSC Recruitment Exam 2019, Page 13.

- ^ Ram Sarup Joon, 1967, History of the Jats, Page 11.

- ^ a b "'Haryanvi movies need govt push'". The Times of India. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Press Trust of India (16 September 2000). "President to give away national film awards on Sept 18". Indian Express. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "Haryana may set up board to promote Haryanvi films". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 3 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

Works cited

- ISBN 978-90-04-27714-4.

- Pletcher, Kenneth (2010), The History of India, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 9781615301225

- ISBN 9780861251551.

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Witzel, Michael (1995), "Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state" (PDF), EJVS, 1 (4), archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007